ADHD

Can ADHD Medication Prevent Suicide?

A study of 146 million U.S. citizens provides critical risk prevention data.

Posted February 12, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

by Grant H. Brenner

ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) is thought to affect over 5 to 12 percent of school-age children—twice as many boys than girls—and to persist into adulthood in at least 5 percent of people.

In spite of controversy, ADHD is considered by experts to be under-diagnosed and under-treated in children and adults. Under-treatment worsens problems with self-esteem, executive function, work, and productivity, with negative effects on mood and anxiety. ADHD persisting into adulthood impairs emotion regulation, sense of self, performance and marital function.

Treating ADHD has been shown to prevent motor-vehicle accidents, injuries, and criminal behavior. People with ADHD are often gifted, but thwarted, and left feeling extremely frustrated and misunderstood.

The economic impact of ADHD is estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars per year, much of that cost borne directly by families, and is a major cause of missed school and work. Diagnosis of ADHD is often complicated as ADHD can overlap with other conditions, and treatment is challenging due to the high cost and the fact that medication alone is not enough. Also, many people assume they have ADHD, when they may not.

Because of concern about rising rate of suicide, there has been more focus on ADHD and suicide crises, which are triggered by unremitting emotional pain and helplessness.

Does Treatment of ADHD Prevent Suicide?

To clarify the relationship between untreated ADHD and suicide, researchers conducted a population-based study, published in the journal Biological Psychiatry (Chang et al., 2020), "Medication for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Risk for Suicide Attempts." Using data from the Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters databases, they correlated data from ages 5 and up. The data covers about 146 million people, spanning 2005 to 2014, representing nearly half of the U.S. population.

They looked at prescription claims to identify common ADHD medications, including stimulants like amphetamine salts (e.g. Adderall), other amphetamine variations, methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin), and a non-stimulant medication (atomoxetine). The database reports on outcomes including emergency department visits, ambulance use, inpatient hospitalization, and suicide attempts, in addition to information about additional diagnoses.

Findings

Of the 146 million people in the database, 3.87 million had ADHD diagnoses, about 48 percent of them women. Of those diagnosed with ADHD, approximately 85 percent received at least one prescription for ADHD medication over the study period. Researchers reported on suicide attempts: 0.1 percent of the men, and 0.2 percent of the women (2288 and 3576 people, respectively), attempted suicide at least once. Patients with ADHD were significantly more likely to attempt suicide than those without ADHD: Men were at a 4.7 percent increased risk, and women at a 4.9-fold increased risk.

During months when people were taking medication, the risk of suicide attempts was 31 percent lower across the whole group. Looking from individual to individual, the risk of a suicide attempt was 39 percent lower when people with ADHD were taking medications than when they were not. These differences were similar for men and women.

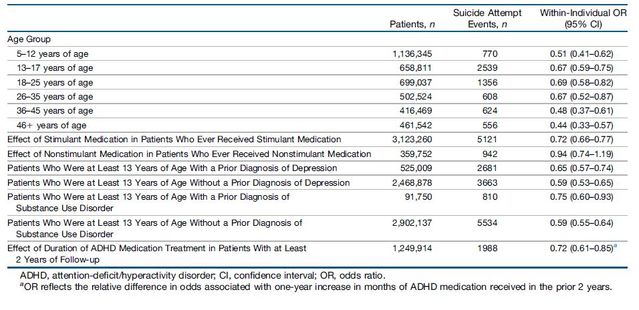

The reduction in suicide risk held for all age groups. (See table below.) It only held for stimulant medication types, and held regardless of whether there was also a diagnosis of depression or substance-use disorder. The longer people were on medication, the greater the risk-reduction; for each year of medication treatment, suicide risk was 28 percent lower.

Notably, patients were at increased suicide risk right around the time they started stimulant medication (in the 3 months prior to and 3 months following), perhaps related to severity of problems leading to the start of treatment, and/or concurrent problems (e.g. depression at that time), and/or because medications facilitated suicidal behavior by restoring motivation, and/or a direct effect of starting medication.

The risk of non-suicide depression-related events was 28 percent lower during medicated months.

Implications

This data from over 146 million U.S. citizens is compelling. This is a very large study, looking at real-world outcomes, with millions of ADHD patients across the age span. While there is room for debate about the appropriateness of medications, the availability of alternative interventions, the reasons for rising ADHD diagnosis rates, and controversy surrounding ADHD treatment in general, these results support the potential protective value of stimulant medications for patients diagnosed with ADHD. Suicide attempts were reduced during months when patients took medications, and with a greater duration of consistent treatment, the risk continued to decline over time.

Special caution is required in the time leading up to and following starting medications, as suicide attempt risk was higher 3 months before and after treatment began. These findings support recommendations that ADHD treatment take place in more specialized care settings, with closer follow-up to ensure adherence with treatment over time and to monitor for increased risk. Many people start and stop medications without contacting their clinicians, and while patients also may prefer to receive refills so they don’t have to come in for appointments, failing to properly monitor for treatment response, adherence, and adverse events puts lives on the line.

Since this is a retrospective database study, forward-looking (“prospective”) studies following actual patients over the course of treatment are required to understand whether stimulant medications really prevent suicide attempts, or whether this is only a correlation. In addition, prospective studies with patients in real-world treatment settings will provide necessary detail about other important factors, adverse reactions, social and occupation impact, and other health outcomes, in addition to clarifying how treatment may protect against suicide.

Interestingly, since it was not possible to tell from this study whether patients receiving medication had been accurately diagnosed with ADHD, it is possible that patients receiving medication who did not have ADHD may have seen a benefit. Future research addressing this question would be useful given how common it is for people to seek, and receive, stimulant medications without a clear ADHD diagnosis.

A Psychiatry for the People post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Neighborhood Psychiatry. All rights reserved.