Anxiety

How Yoga and Breathing Help the Brain Unwind

Research shows normalization of neurotransmitters in anxiety and depression.

Posted January 16, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

"What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter—a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue." —Henri Matisse

Nerves of Steel

Anyone who has struggled with anxiety and depression, or knows someone who has, will understand how the body’s energy is out of balance. We see this over short time frames, hour-to-hour, day-to-day—with abrupt changes in mood, sudden anxiety, crashes in willpower and motivation, bursts of activity, and other difficulty reacting constructively to stresses—and over longer spans of time, with chronic fatigue, burnout, persistent difficulty resting and recharging, disrupted sleep, and trouble pursuing long-term plans.

Rather than reacting to challenges with a proportional response, maintaining regular activities, and being able to return to a pre-activation state, people with anxiety, depression, and related conditions, such as post-traumatic stress, get stuck in states of both under- and over-activation, with difficulty smoothly transitioning back and forth as required by circumstances.

The body manages this balance via the autonomic nervous system, with various bundles of nerves projecting from key areas of the brain throughout all areas of the body. The autonomic nervous system operates largely on autopilot, and unlike the nerves which signal our muscles to move on command, we cannot easily exercise conscious control over those reactions, like our heart rate, how fast we breathe, how much blood flows to our legs and away from non-essential systems when we need to hustle, and generally the driving and damping forces that, in health, serve to keep us functioning within sustainable operating parameters.

It is the sympathetic nervous system, associated with adrenaline and fear responses, which makes us leap into action or freeze in ready-to-bolt fear, and the parasympathetic nervous system that comes online when stress has abated, returning the body to baseline and restoration.

The parasympathetic nervous systems include the Vagus Nerves (aka Cranial Nerve X [10]), which emerge from the base of the brain as a pair, one for each side of the body, sending fibers to the heart, lungs, adrenal glands, and other vital organ systems. Stimulation of the Vagus Nerves with a surgically implanted device similar to a cardiac pacemaker, for example, can effectively alleviate depression symptoms.

The parasympathetic nervous system quells activation via a brain-wide inhibitory neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), lowering the volume on overall neuron activity, as contrasted with glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, which amps up neural activity. Researchers study the effects of various interventions for anxiety, depression, and other conditions using the Vagal-GABA Theory. In the case of yoga and breathing exercises, the hypothesis is that these practices enable us to directly impact how our brains work by stimulating the vagus nerve, and thereby increasing GABA levels in key areas which raise parasympathetic nervous system “tone,” balancing out relatively excessive sympathetic nervous system activity.

Clinical effects of yoga and breath practice

In this groundbreaking study, the first of its kind to look at changes in GABA levels as a function of yoga and related practices, researchers compared the effects of a 12-week course of Iyengar yoga on clinical outcomes and brain GABA levels in a group of healthy volunteers and a group of people with depression and anxiety. The control group included 17 people, and the depression and anxiety group 15 people diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD, but excluded those with heightened suicide risk for safety reasons). There were also five people in the MDD group with additional diagnoses of PTSD, three with panic disorder, and four with alcohol use disorder.

The yoga regimen included backbends, inversions, and lying still on one’s back to enter a state of deep repose (savasana), with group sessions with a skilled yoga teacher totaling 3 hours per week and home practice for about 1.5 hours a week. Along with Iyengar yoga, the MDD group practiced "coherent breathing." This is an easy-to-learn breath practice thought to raise parasympathetic tone by reducing the number of breathing cycles to five per minute, as the heightened sympathetic activity is associated with increased respiratory rate.

Prior research has shown that yoga and coherent breathing have beneficial effects across a variety of clinical conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress, among others. This suggests that there is a “transdiagnostic” effect of such practices which transcends diagnostic categories related to the underlying autonomic nervous system imbalance and that normalizing the physiological response can improve symptoms and bolster resilience.

In addition, consistent with the Vagal-GABA Theory, the authors hypothesized that GABA levels would normalize as a result of the research intervention, measuring GABA activity in a key brain area known as the thalamus. The thalamus has been dubbed the “switchboard” of the brain by some neuroscientists, because it serves as a communication hub to interconnect distant areas of the brain with one another, critical to the maintenance of normal global brain network activity. Specifically, the thalamus is a key waystation carrying vagal signals around the brain, and thalamic GABA levels are lower in depressed and anxious patients.

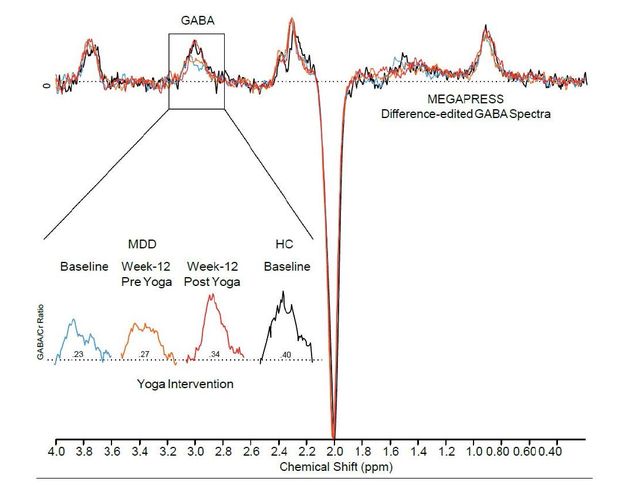

Researchers looked at GABA activity using Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) at three time points throughout the study: at the beginning and then before and after yoga/breath practice sessions after 12 weeks. MRS is a form of MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging, a common neuroimaging tool used in clinical care and research), which allows us to measure key neurotransmitter levels. In order to see whether any observed effects were specific to GABA, they also looked at NAA, GLX (involved in excitation), and Choline (involved with parasympathetic activity in a different way) levels, which may also be affected by autonomic nervous system imbalances. Clinical outcome measures included the Beck Depression Inventory, (BDI), the Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-State), and the Exercise-Induced Feeling Inventory (EIFI), which measures tranquility, positive engagement, revitalization, and physical exhaustion.

GABA levels after yoga and breath practice in depression and anxiety

Their initial findings, while requiring further investigation, are remarkable. Following 12 weeks of yoga and coherent breathing practice, study participants in the depression and anxiety group showed normalization of thalamic GABA levels on MRS pre- and post-session. As we can see in the MRS curve from a study subject, the healthy control and patient curves come together.

At the same time, the BDI and STAI-State scores showed statistically and clinically significant positive changes. In those with depression and anxiety, after practice, the tranquility, revitalization, positive engagement, and physical exhaustion sub-scales all showed improvement.

Last, only GABA levels were significantly affected by the yoga-coherent breathing intervention—the other neurotransmitter levels, though showing some baseline difference between healthy controls and depressed and anxious patients, as one would expect, were not significantly affected by the study intervention, suggesting a unique role for the Vagal-GABA connection.

Implications for care

Aside from requiring a significant time commitment to complete a full 12-week course, there are few reasons why we wouldn’t integrate such practices into part of a wellness routine, especially if we are working toward more resilient stress responses in the face of anxiety, depression, trauma, substance-related conditions, and other difficulties with stress management.

In some cases, for physical or medical reasons, not all of the practices are possible, but the majority of people can do the breathing and deep relaxation poses. In addition, Iyengar yoga particularly focuses on using physical supports, such as cushions and yoga straps, to ensure both proper form as well as the sense of safety and body integrity which comes from avoiding over-extension and missing touch feedback from around the body during yoga. Especially for those with body-related issues, starting within a safe framework is essential to allow the parasympathetic system a chance to start to kick-in and both de-escalate and counter-balance excess sympathetic tone.

Dr. Chris Streeter, the Primary Investigator of this study and Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Boston University Medical School, was kind enough to share additional insights via an email interview.

Who should consider including yoga and coherent breathing into their recovery plan? She notes, “As with exercise, the best person is the one who is interested in this type of intervention.” For those who may have physical limitations, “The yoga intervention has been modified for individuals using a chair, by trained yoga instructors. The breathing intervention can be done by most people.” As can also happen with meditation, Dr. Streeter notes that one participant experienced increased worry during breathing exercises, and so did additional yoga practice instead.

Patients should discuss any additions to their treatment with their current health care team. It’s important to recognize that yoga, breathing, and other practices are not a substitute for medical care, and no treatment ought to be changed or stopped as a result of incorporating additional practices unless it is part of a formal treatment plan.

This research is an important foundation, kicking off an avenue of research in which the neuroscience of yoga, breathing, and other integrative practices can be understood on a systemic level. It is important to investigate what other changes are observed which correlate brain activity with clinical and functional outcomes, from the level of specific brain regions and neurotransmitters to global effects on brain networks.

According to Dr. Streeter, “The goal is to provide enough evidence-based studies so that yoga can be integrated into treatment plans for depression and anxiety. Yoga can be considered as an adjunct to treatments, especially depression where around 40 percent of individuals treated with antidepressants do not achieve remission of symptoms.”

LinkedIn Image Credit: shurkin_son/Shutterstock

References

Chris Streeter, Patricia L Gerbarg, Greylin H Nielsen, Richard P Brown, J Eric Jensen, Marisa Silveri. Effects of Yoga on Thalamic Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid,

Mood and Depression: Analysis of Two Randomized Controlled Trials. Neuropsychiatry (London) (2018) 8(6), 1923–1939.