Fear

The Elephant in the Room… Was Screaming

Playing with the heavy topics can get uncomfortable.

Posted June 14, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Trigger warnings may backfire.

- Overprotection may be countertherapeutic.

- History is often troubling; studying history should trouble us.

Nearly a decade and a half ago I joined an interdisciplinary event, staged at a major urban university, called “Three Days of Play.” The celebration showcased large lectures, meetings with small groups of faculty and students, and the culminating event, a festive, audience-driven evening that featured contests and wisecracks.

In a 10-minute, rapid fire, PowerPoint-provoked, free-association game of my devising, I double-dared the SRO audience to shout out reactions, memories, one-sentence stories, and personal recollections about famous toys. A giant egg-timer ticked off the seconds. Tick, tick.

I showed a series of slides. “The Joy of Joysticks,” solicited ideas about video game play; “Plastic Sorcery” drew out stories about conjuring playnarratives with Barbie dolls. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain led us into creativity and crayons. And “What Goes Around Comes Around” noted how hula hoops disadvantaged the pear-shaped.

The Medium Was the Message

We worked our way, entertainingly, through minilessons in technology (Silly Putty), spatial reasoning (Erector Set), play-mediated creativity (LEGO),), visual jokes under pressure (Pictionary), diverting children quarantined during a polio epidemic (Candy Land), the vestibular system and pleasurable dopamine flooding (rocking horses), literacy learning (Scrabble), imagining scale (Tonka trucks v. Matchbox cars), improvisation (The Stick!), and meditation (“To Yo-Yo You Need to Let Go”).

Comedy had shown the way toward weighty subjects. Or to put it another way, the medium, play, was also the message: Play!

A Surprise Reveal

Planners aimed to free up creativity in the academy, to liberate teaching and learning, and perhaps, unshackle research! Underlining the serious commitment to transformational institutional aims, the university’s president hosted a lunch with the provost and several academic deans and chairs of a diversity of departments in attendance.

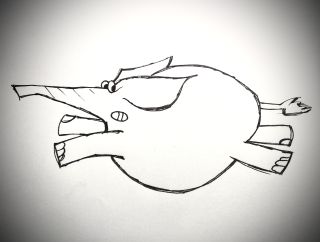

During dessert, the design department faculty treated us to a surprise reveal, a trick-elephant prototype plush toy engineered to be passed around a seminar. A couple of ingenious industrial design majors had cooked up the toy after one of their colleagues had inadvertently used a homophobic slur in a design critique. (“That’s so gay!”) Here was the elephant’s secret: Any student could squeeze a button hidden under one of its large ears, and then following a random interval, the beast would emit a caterwauling so ear-splitting and insistent that classroom discussion would be halted.

The point? Anybody who encountered anything uncomfortable could, without saying so themselves, loudly signal that the discussion had edged into dangerous territory. The class would then explore what had gone wrong. The New York Times picked up the story! As the Times’ reporter put it, “you couldn’t just ignore [an] issue or bury hurt feelings.” The designers stood up for the voiceless!

Ignorance Isn’t Bliss

I looked over at another invitee, a prominent play-theorist and advocate, and noted the steam piping out of his ears. A career in surgery and psychiatry had obligated him to treat alarming and life-threatening circumstances. That an academic exploration should be obstructed by anonymous fear? Unthinkable. A post-screaming-elephant kerfuffle ensued.

I tried to sum up, gently. Wasn't the classroom, in fact, just the right occasion to encourage students to speak up, and then crucially, for them to learn to speak up for themselves? Wasn't classroom give-and-take a kind of instructive play? And wasn’t playful dispute precisely the way to overcome the twin bugaboos of teaching—students’ diffidence and reticence? Wouldn’t peer-pressure driven timidity serve students poorly in the long run? Wasn’t free discussion how professors would give students their money’s worth?

Trigger Warnings Can Backfire

Back in 2009, no one in the room had heard the phrase “trigger warning.” My argument at the luncheon—principled, conventionally libertarian, and, I now understand, slightly naïve about students’ vulnerabilities—portended the discourse that continues to sharpen on college campuses.

Should professors warn students and allow those who feel hemmed in to opt out of uncomfortable discussions? With good intention and on the advice of tort lawyers, the practice spread across American campuses. But, in 2016 the University of Chicago came out against such protocols, declaring, “We do not condone the creation of intellectual safe spaces where individuals can retreat from ideas.” Cornell University recently reiterated the position, noting that advance warnings “would unacceptably limit our students’ ability to speak, question, and explore.”

Bonnie Zucker, a clinical psychologist who specializes in treating trauma and anxiety, wrote that content warnings in university classrooms—originally intended to protect survivors of trauma—had undergone mission creep. The cautions “expanded to protect others who might be distressed by certain content.” However serviceable avoidance proves in the short term, warnings that enable learners to avoid distressing content, she wrote, will backfire as “anticipatory anxiety” ends in a loss of resilience. Relying on trigger warnings, Zucker concluded, “is countertherapeutic.” Evasion isn’t bliss.

History Is Both Inspiring and Troubling

My historical training has left no option to look away from either past triumphs or catastrophes. Studying history imposes upon us the big questions of morality and war, just leadership and fair policy, individual liberty versus social responsibility, high-flown rectitude against everyday practice, myth-making set against fact, unequal justice for the powerful and the marginal, dogma vs. inquiry, and so on. History is full of complex, intellectually knotty questions; history features an inexhaustible supply of virtuous villains and wicked heroes.

I’ve been lucky enough to chase these basic questions interactively both in small university classrooms and for very large museum audiences. Even when teaching survey courses necessarily heavy with chronology and information, I determined that the rollicking, evenhanded, interactive, courteous, chancy, invigorating, and, yes, playful mutual exploration of ideas would enrich learning and narrow the distance between professor and student, exhibit developer and audience. Good teachers learn the difference between inquiry and nattering.

Playing with the Heavy Topics

Nobody was safe from edgy inquiry in my classes, least of all me. And no matter how weighty the topic of the museum exhibit, I was determined to leave audiences thinking and smiling.

So, now at some distance from both enterprises and even amidst howling cultural division, I must say that I’m bewildered by the efforts to protect learners from uncomfortable discourse and alarmed by the censorious, politically opportunistic attempts to suppress curricula.

If the professor or the interpreter is always playing for mutual insight above on a high-wire, ladies and gentlemen, the screaming elephant now bellows in the center ring.

References

Bonnie Zucker, “Trigger Warnings and the Stifling of Emotional Growth,” Psychology Today (May 22, 2023).

Kate Zernike, “An Elephant in the Room,” New York Times, (December 24, 2008); Arthur Jensen, Kimberly Pearce, Robyn Penman, “The Elephant in the Room: Righteous Minds and Cosmopolitan Communication,” CMM Institute, (June, 2021).

Scott Eberle, “Defying Gravity: Playing with the Heavy Topics,” History News, (Autumn, 1998); David A. Gerber, “Confronting a Source of Contemporary Student Disengagement,” Proceedings of the H-Net Teaching Conference, (May, 2023); David A. Gerber, “Are We Giving Students Something Worthwhile to Talk About?,” AHA Perspectives, (January 12, 2018 and David A. Gerber, “Confronting the Paradox of Expertise: Leave Your Comfort Zone and Reinvigorate Your Teaching,” AHA Perspectives, (February 25, 2019).