Attention

Sexy Breast Cancer Campaigns Do Demean Women. So What?

Using sexual objectification to get attention for a Cause has implications

Posted December 12, 2012

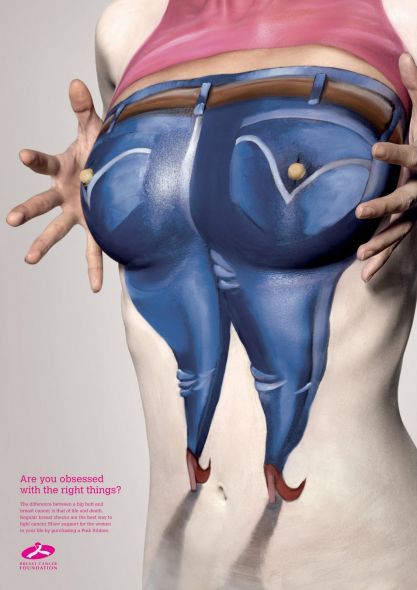

Breast Cancer Foundation Ad Series from Singapore

In my last post I asked, "Do Sexy Breast Cancer Campaigns Demean Women?" The answer was yes. I identified six sexually objectifying techniques commonly used in breast cancer awareness campaigns to get attention, raise money, and lure people to the Cause.

- Use women's bodies as literal objects (canvases, ribbons)

- Hone in on the breasts (chest-level videos, animatronic boobs)

- Use objects in place of breasts (cupcakes, bowling balls)

- Objectify breasts with language (jugs, racks, funbags)

- Depict breasts as things to be touched or groped

- Show women as objects of the male gaze

There are numerous examples of these sexually objectifying techniques in the marketing materials of fundraisers, charities, and public service campaigns. They use sex and women’s bodies (or parts of them) to sell products and ideas. Sexual objectification is the means to an end. But since advertising is an applied form of persuasion, the ends are not likely to include active thinking about breast cancer. Indeed sexy advertisements (even those oriented toward awareness) use nudity, physical attractiveness, and sexual content to tap into the unconscious—a space where attitudes, emotions, skill sets, and cognitive shortcuts work automatically. Advertisements draw upon sensory experiences, memory, and heuristics to create affective associations, not conscious scrutiny.

One of the most common devices in advertising is the use of gender stereotypes that attribute specific traits to women as a group. Women are portrayed in a limited number of social roles (e.g., underrepresented in working roles but persistently visible as mothers and housewives), in decorative as opposed to functional roles, as lacking authority, as dependent upon others (especially men), as alluring and flawlessly beautiful, as the object of a societal gaze that judges women based on appearance alone, as sex objects, and as consumers of sex as the primary means to achieve happiness. What’s more, the sexual objectification of women and pornification across media and other entertainment outlets have increased substantially over time, a trend that corresponds with the rise of the internet, excessive advertising, and the use of shock value to break through the noise.

Shock value comes in a variety of forms, but the explicit portrayal of women as commodities or sexual objects is becoming more rampant and more normalized. A report from an American Psychological Association task force (2010) found that even young girls are exposed to toys, video games, clothing, cosmetics, cartoons, youth magazines, music, and various programming that is rife with sexual slogans and imagery. As those little girls grow up, they will be exposed to breast cancer propaganda that offers them ta-tas t-shirts, boobstagrams, and porn hubs for the cure while it tells them to feel their boobies as a measure of breast health. The marketplace will also prime them to believe that choosing their objectification is empowering.

Women do learn to accept the seeming inevitability of sexual objectification. But there is also strong evidence that when it is internalized, sexual objectification contributes to a range of negative outcomes.

Sexual objectification is tied to eating disorders, habitual body monitoring, and body shame. It is linked to poor self-esteem, lack of self-confidence, limited self-worth, diminished life satisfaction, and depression. It is associated with declines in cognitive and physical functioning and contributes to sexual dysfunction. Sexual objectification also contributes to negatives attitudes about women that may lead to assumptions that only young healthy women have social value, or that women are stupid or incompetent, therefore incapable of leadership and political efficacy. Objectification that is sexual in nature fosters a cultural environment in which sexism, harassment, child pornography, rape, and violence against women are more easily accepted.

Now add this list of negative effects to a breast cancer diagnosis. Without conscious scrutiny similar outcomes are likely to apply. Body monitoring, body shame, lack of self-confidence, diminished life satisfaction, and sexual dysfunction have been documented. Are these outcomes the result of breast cancer alone, or are they implicated by social pressures to conform to an idealized model of femininity and sexuality that pervades advertising, popular culture, and now a new genre of breast cancer campaigns? Do the means justify these ends?

Supporting a social cause oriented to women while undermining women’s status in society is counterproductive. But since advertisers want to tap into our unconscious minds, conscious scrutiny of media messages can help to mitigate the effects. Whether it is a Dolce & Gabbana ad that glamorizes male dominance or a breast cancer awareness campaign that sexualizes women while glossing over the realities of a serious disease, media literacy has become a necessary tool for the pursuit of gender equality and for the fight against breast cancer.

Dr. Gayle Sulik is the author of Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women's Health. More information is available on the book's website.

© 2012 Gayle Sulik, PhD ♦ Pink Ribbon Blues on Psychology Today