Health

Rene Descartes—Villain or Savior for Mental Health Care?

Is medicine able to advance as a science?

Posted August 21, 2018

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) was a brilliant philosopher, mathematician, and scientist. Most scholars consider him responsible for modern medicine’s splitting the mind and mental issues away from the body and its diseases.1-3 As a result, the mind and its mental disorders became the province of the 17th century church while medicine and science focused on the body and its diseases to lead a new scientific revolution.

Fast forward to the present. Although dramatic advances in diseases followed, including doubling our life survival during the 1900s, we nevertheless face extraordinarily poor mental health care as a result of medicine’s isolated focus on the body and its diseases. For example, from the Healthy People initiatives, just 25% of patients who need mental health care receive it (compared to 60-80% of patients with disease problems). As well, the care they do receive rarely meets minimum standards.4,5 This occurs because medicine, its administrative structure as well as its clinicians, for the most part, ignores mental issues—even though the National Alliance for Mental Illness tells us that mental disorders are the most common problems physicians face in practice. What other evidence demonstrates that medicine ignores mental disorders?

Political, financial, administrative, and other power centers perpetuate an isolated focus on

diseases. For example, program level funding for research in 2016 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was $30.1 billion yearly, with almost the entire budget devoted to diseases.6 The institutes with a focus on mental health problems received less than 10% of the budget to guide physicians in caring for the most common problem they will see in practice, that is, about half of all their patients.6

Here’s the root cause of today’s problem, the one that must be corrected if mental health is to improve. From the National Institute of Mental Health, we know that, because of worsening shortage of psychiatrists, 85 percent of all mental health care is provided by primary care and other medical practitioners. Yet, the American Association of Medical Colleges, the governing body for medical student education, reports that less than 3% of total medical school teaching time addresses the clinical skills needed to provide mental health care—the most common problem its graduates encounter in practice!7 If training were proportional to need, it would be 50 percent or greater. Most residency training conducts even less teaching in mental health care.

You hear about the appalling effect of shorting mental health care every day. There were nearly 250 million opioid prescriptions written by untrained physicians in 2013—enough for every adult to have one bottle (30-90 tablets in each)!—and approximately 18,000 overdose deaths yearly from the unnecessarily prescribed opioids.8,9 As well, physician graduates are not trained to address suicidal patients even though about half of these patients visit their physician in the month beforehand. Training could help prevent the 43,000 suicide deaths yearly.10 Rampant depressive and anxiety disorders are seldom diagnosed and almost never treated correctly.

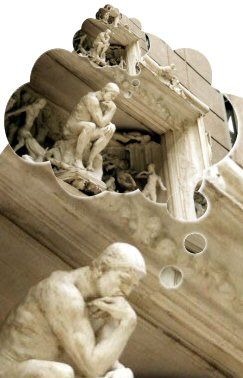

Here’s the question: Do the many adverse effects of the mind-body split mean we should blame 17th century Descartes? Yes is the usual answer one gets, seemingly in passive acceptance of the permanence of the mental health problem. Let’s think about this and try to get beyond this answer—there’s more to it. While the ‘yes’ answer may be logical, Descartes also revolutionized medicine and science by thinking in a radically different way. He guided medicine and science away from church dogma to scientific method! Maybe this is the Cartesian legacy we should follow—changing our way of thinking. Here’s a closer look regarding which legacy of Descartes will be most useful in correcting medicine’s mental health problem.

The greater than 1000-year scientific dry spell before Descartes and the Enlightenment (16th and 17th centuries) almost completely arrested progress in medicine and science. Medical teaching and practice were so thwarted that they were based on pre-scientific work done in the second century AD.

A dramatic turnaround occurred with the Enlightenment. Descartes led a truly quantum change to a new paradigm when the new scientists and their research gave birth to modern, scientific medicine. These conceptual and research advances spawned the unrivaled—almost miraculous—benefits11 we accept today as routine. Unfortunately, by ignoring the mind, poor mental health care was a byproduct. The divergent paths of care for medical and mental disorders suggest that, earth-shattering as the Cartesian advances were for diseases, something needs to change—unless we believe a philosophical idea that began in the radically different circumstances of the 16th-17th centuries continues viable to this day.12

Many object immediately to the idea of change: “…medicine’s disease care must not be jeopardized…” they say. Agreed. But is there a scientific way to change and still retain good disease care?

There is. The modern theory of science, general system theory, identifies it. The theory dictates that the focus of any science encompass all facets of its interacting component parts. The scientific focus of medicine is, of course, the patient. The patient has three component parts: biological (disease), psychological, and social. This was articulated in the 1970s as the systems-based biopsychosocial (BPS) model.13 The model, you can see, does not exclude the disease aspect of the patient. Rather, it integrates all three components. Here’s the theoretical and conceptual problem with the mind-body split: it almost exclusively addresses the body/disease part, omitting the psychological and social aspects involved in mental disorders. That is, modern medicine practices a biomedical model and, thereby, is not consistent with the modern theory of science.

Extensive research data indicate that guidance by the BPS model produces improved medical as well as mental health care! But what have other sciences found when they used a general systems approach? Further encouraging, for example, from the very same 17th century of Descartes, Newtonian physics was transformed into the new physics by Einstein and many others in the 20th century without sacrificing Newton’s seminal advances.14 Why can’t medicine build on Descartes’ mind-body split in a similar way, one that continues to reap its disease benefits but expands to include the mind and mental issues? Ignoring progress in other sciences (cybernetics and modern biology, for example, as well as physics), medicine has not changed its thinking in over 400 years.

Effective as medicine has been, we must consider whether medicine’s progress from a philosophical and intellectual vantage point arrested after the impact of Descartes, perhaps blinded by its successes. Has its conceptual development run aground?14 Since the Enlightenment, medicine has simply played out the productive disease hand, incrementally solving each problem produced by research, without recognizing the ravages it has worked on those with mental health problems. There has been no parallel progress for mental disorders even though medicine, not the Church, has long been responsible.

The is a serious charge—that the field of medicine lacks the intellectual and conceptual wherewithal to build on Descartes.12 Descartes, in fact, modeled what we need to do. Of greater importance to modern medicine than the now effete mind-body split, Descartes’ success occurred because he did what we must do: Radically change our way of thinking!

References

1. Porter R. What is Disease? In: Porter R, ed. Cambridge History of Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011:71-102.

2. Porter R. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind–A Medical History of Humanity. New York: WW Norton and Company; 2009.

3. Sullivan M. The Patient as Agent of Health and Health Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

4. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. In: Services USDoHaH, ed. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000: 76.

5. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Mental Health and Mental Disorders. Healthy People 2010. Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government Printing Office; 2000:18-3 to -32.

6. Dept. of Health and Human Services. HHS FY2016 Budget in Brief. In: Health NIo, ed. US Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2016.

7. Association of American Medical Colleges. Basic Science, Foundational Knowledge, and Pre-Clerkship Content–Average Number of Hours for Instruction/Assessment of Curriculum Subjects. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2012.

8. National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic–Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. Washington, DC2017.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. In: Prevention CfDCa, ed. Washington, DC: CDC; 2016.

10. Hogan MF, Grumet JG. Suicide Prevention: An Emerging Priority For Health Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1084-90.

11. Watts G. Looking to the Future. In: Porter R, ed. Cambridge History of Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011:298-329.

12. Brown TM. Cartesian dualism and psychosomatics. Psychosomatics 1989;30:322-31.

13. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977;196:129-36.

14. Capra F, Luisi P. The Systems View of Life–A Unifying Vision: Cambridge University Press; 2014.