Career

Putting Forgetting to Creative Work

Intentional and unintentional forgetting in teams and organizations.

Posted August 6, 2020

Successfully realizing positive change, whether in individuals or in teams, is tough work. It's tough work because of the many different challenges that must be met when people strive to generate, iteratively revise, and implement good innovative ideas.

But that's not all.

Keeping a new idea or novel perspective in mind, carrying it forward from day to day, may also demand that we forget. We may need to set aside—or thoroughly unlearn—our previous ways of doing and thinking. For good innovations to both survive and thrive, sometimes forgetting or unlearning may be crucial.

Yet such unlearning can itself be demanding. In a 2020 report documenting a series of semi-structured interviews with 30 members of 10 new product development teams, researchers at the University of Liechtenstein identified a common thread of informational overload. New product development team members in industries ranging from clinical informatics to electrical engineering to lighting solutions, spoke of the flood of new information that they regularly encounter—and how this makes it hard to know what to leave behind. "The problem is, that more and more communication channels are opened and none are closed," and "because developers are overloaded with new things [they] do not always notice that old things are obsolete." (p. 590)

How to take advantage of intentional forgetting and unlearning

Novel ideas often need to compete with many already existing ideas, including ways of thinking and acting that have become deeply entrenched habits. If our previous ways of doing things have become obsolete, or there are new organizational processes, objectives, or challenges that we are facing, it may be helpful to purposefully try to "unlearn" earlier methods.

In the daily course of things, with ongoing time pressure and deadlines, "unlearning" can prove challenging. It can take time, attention, and effort to step back and evaluate well-established routines and conceptual frameworks to ask if they are still necessary, or if they are optimized to current needs and goals. Providing specific and regularly occurring times for reflection and evaluation, for stepping back and re-assessing how and why particular routines are "the way we do things" can be valuable in identifying outdated ways of doing and thinking, before they become larger and looming problems.

By frequently and periodically adopting a skeptical, questioning, and flexible mindset—such as asking, why, exactly, certain assumptions are being made—individuals and teams can better stay alert to the wider, often rapidly changing and unpredictable context in which they are situated. In the words of one New Product Development team member interviewed by the University of Liechtenstein researchers, "A lot about creativity and a lot about learning and evolving and growing is about being skeptical with what you really know" (p. 594).

Another way to step outside old frameworks is to literally "step outside" in a separate and discrete "island" of time and space for a team to work as they seek to develop new ideas. One NPD team member described how a team charged with developing an entirely new product spent one day a week, for about a year, in a separate space, without phones, and isolated from daily business, "completely without templates." (p. 595)

Clearing a space of the many sorts of "material memory" that teams and individuals acquire, such as notes, manuals, prototypes, models, and blueprints, may paradoxically pave the way for the emergence of new ideas and new ways of doing. Once in a while selectively and purposefully removing notes, documents, or other bits and pieces from earlier (successful or not-so-successful) creative projects—stashing them in a drawer, piling them in a box, moving them to a different digital or paper folder, out of sight—can remove physical reminders of earlier modes of thinking, clearing the way for fresh forays in creative thought.

But unintentional forgetting is important too

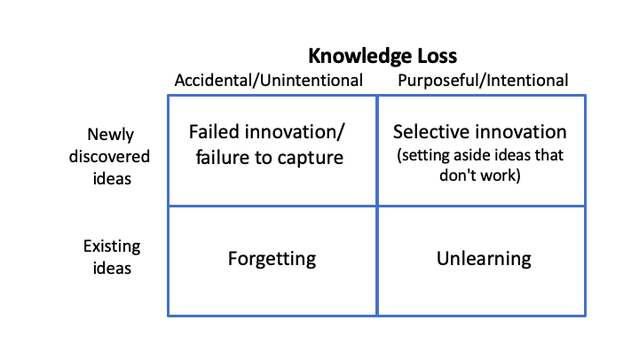

Accidental and unintended loss of knowledge is perhaps what comes most quickly and vividly to mind when we think about how knowledge loss occurs, and is shown in the lower-left quadrant of the following schematic mapping of types of knowledge loss processes.

Unintended knowledge loss from a team may occur through the departure or turnover of team members, or organizational restructuring, or inadequate record-keeping. It may also occur through the passage of time or the introduction of new procedures, tools, or devices. Research with surgeons who perform hip replacement operations shows that, even on the timescale of days, switching to a new task or a slightly different replacement device, brings with it some loss of "procedural know-how." Even for experienced surgeons, the first time using a new device leads to a marked increase in the duration of the surgery procedure, and gaps between when the same device is used (device-specific forgetting) can modestly, but still significantly, increase the surgery duration. Given this, the gains from introducing any new device or procedure need to be "large enough to compensate for the short-term disadvantage of starting up on a new learning curve and, also, of increasing the chances of knowledge depreciation over time" (p. 2605).

Still, it's complicated: With too much repetition, our (or our surgeon's!) motivation, attention, and engagement may wane, or drastically drop off, as we become bored and fatigued with the same-old execution of steps. Variety can bolster motivational commitment—and foster the mastery of important skills and know-how that can be adaptively applied in other situations that we may encounter.

Handled adroitly, and with a steady eye on our ideals, both unintentional and intentional (purposeful) forgetting can help us creatively move forward whether as individuals or as teams. Both intentional forgetting and unintentional forgetting can play sometimes pivotal roles in adapting to needed change. Each can either help propel positive change forward, giving it momentum, or stand in the way, slowing and blocking new ways of thinking and doing.

To think about

- What ways are you or your team tightly holding on to past ways of doing things that would be better discarded, or silently slipped into a drawer and left behind?

- Conversely, are you too cavalier or overly casual about the process of physically capturing and communicating valuable knowledge? Do you have strong communication and good documentation nets to capture you and your team's established ways of doing and lines of reasoning? And what becomes of newly emerging ideas that might inspire and impel you on a fresh course?

- In the shorter-term, working on a single or a few tasks for a brief time (hours, perhaps days) may often be best. Longer-term, though, are you interspersing repeated tasks with different or varied ones—adding the spice of variety—building your and your team's longer-term competencies, engagement, and knowledge?

- Do you welcome a skeptical and flexibly questioning mindset—recognizing that a little well-placed doubt may leave everyone better prepared to tackle unforeseen difficulties, large or small, and better ready them to make the most of newly arising opportunities?

References

De Holan, P. M., & Phillips, N. (2011). Organizational forgetting. In Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management (M. Easterby-Smith and M. A. Lyles, Eds., pp. 433–451). John Wiley & Sons.

Klammer, A., & Gueldenberg, S. (2020). Honor the old, welcome the new: An account of unlearning and forgetting in NPD [new product development] teams. European Journal of Innovation Management, 23, 581–603.

López, L., & Sune, A. (2013). Turnover-induced forgetting and its impact on productivity. British Journal of Management, 24, 38–53.

Ramdas, K., Saleh, K., Stern, S., & Liu, H. (2018). Variety and experience: Learning and forgetting in the use of surgical devices. Management Science, 64, 2590–2608.

Staats, B. R., & Gino, F. (2012). Specialization and variety in repetitive tasks: Evidence from a Japanese bank. Management Science, 58, 1141–1159.