The Secret Motive Underlying Every Human Interaction1

Since I've already committed the sin of clickbaiting, I won't double-up on my transgressions by burying the lede—let’s get straight to the secret motive underlying every human interaction.

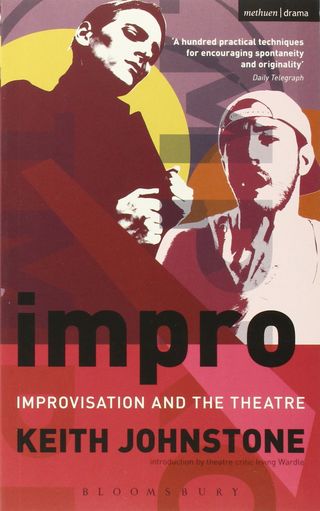

It actually isn’t my secret at all. It belongs to acting coach Keith Johnstone, author of the 1979 book Impro: Improvisation and the Theater.

Here it is:

Every human interaction—every utterance, every smile, every text—involves one person elevating or lowering their level of dominance or submission with respect to the other. Johnstone calls this relative level of dominance and submission “status” and argues that all conversations act like a see-saw of status.

Johnstone discovered this secret while brainstorming ways to get his acting students to converse more authentically. They kept delivering stilted, non-natural-sounding performances. It was only when he told them to deliver each line as if they were attempting to change or manipulate their level of status that they began to deliver credible performances.

To test his theory, let’s pluck a random scene from a random2 popular movie and see if we can dissect all of the interactions through the lens of status.

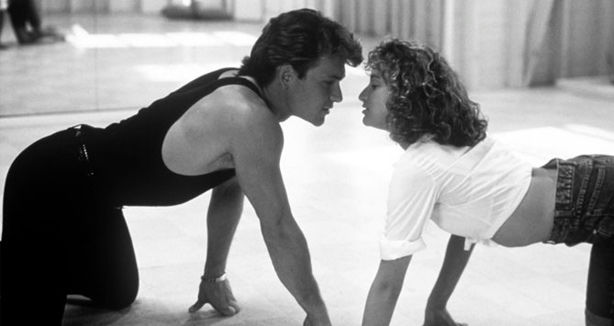

Dirty Dancing: A Lesson in Status

It is the end of the movie. Johnny has been fired (status demoted) for fraternizing with the clientele’s daughter to the tune of "Hungry Eyes". This was a problem largely because he dared romance with someone outside his socioeconomic status.

Baby sits, dejected, at a table with her parents. She could not be lower status—a grown woman forced into a child’s role, stuffed into a dark corner against the wall.

Johnny strides in wearing his leather jacket and his delicious combination of pure masculinity and graceful vulnerability. He plays high status to Baby’s parents with that timeless line: “Nobody puts Baby in the corner.” No one, in other words, makes Baby low status on his watch. He follows this bold statement by physically elevating her status—reaching out his hand for her to stand and join him on stage.

He always does the last dance of the season (high status). Someone tried to tell him not to (attempted to quash his high status) but he’s going to do it anyway, and with his kind of dancing (nice try, he’s still high status).

In his speech he elevates Baby’s status again by rechristening her with her given name—Miss Frances Houseman. It is hard to imagine a lower-status nickname than Baby3, with its connotations of complete powerlessness and asexuality. Frances Houseman, on the other hand, is stately, and we know from earlier in the movie that she was named after the first woman in the Cabinet.

Her father stands, about to play high status and put a stop to these shenanigans. Baby’s mother, to this point in the movie having played low status to her husband, restrains him with a hand on his arm and unexpectedly pulls high status on him: “Sit down, Jake.”

Baby and Johnny dance. It is joyous. They end the dance by Johnny quite literally lifting Baby to the skies, above the crowd, above her parents, above her own self-doubts.

On high she laughs. It is beautiful.

The Problem with Status

There are many ways in which we enjoy these status manipulations, even making games out of them. We delight in teasing our siblings about their incompetence and unattractiveness. Many of us enjoy a vicarious status rush when our favored sportsball team wins their coveted trophy or whatever. We exult in sudden status reversals, underdogs winning in an upset and celebrities brought low.

What we don’t love is risking losing status. For we deeply fear revealing our innermost selves and having those selves rejected.

Which, it turns out, holds us back from everything from flattering pictures to human connection to creativity.

Pictures: Johnstone observes, “[i]f someone points a camera at you, you’re in danger of having your status exposed, so you either clown about, or become deliberately unexpressive.” Neither yields attractive portraits.

Status risks also explain why every starry-eyed ballad and television sitcom dwells on the quandary of whether and when to reveal romantic feelings for another. For the first person in a relationship to utter the famous three words forever holds higher status than the person who went second, and if you ever hear back “I…think you’re really great too,” you have been delivered an enormous status blow.

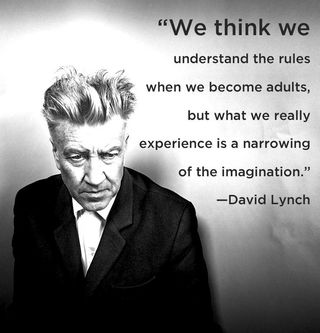

Johnstone also claims that most of us struggle to be truly creative because we fear our own ingenuity, the strangeness of our ideas and what they might reveal about us. He argues that true creativity comes out of generating ideas freed from the fear of censure, freed from the cultural rules we’ve been taught about how we are to think and behave.

For in intentionally choosing vulnerability lies great strength. In an interview with Forbes, bestselling author and research professor Brene Brown says, “The difficult thing is that vulnerability is the first thing I look for in you and the last thing I’m willing to show you. In you, it’s courage and daring. In me, it’s weakness.”

In a post to appear soon in a different venue I consider some of the ways in which knowledge of status can inform education, ways in which we can break down some of the natural status differentials in the classroom in order to more authentically connect with our students.

But the classroom is just one social venue in which taking status risks can benefit us as people.

Johnstone challenges us to choose vulnerability in all of our relationships and creative work, to release our fear of the pain of failure, to reject all of the tricks we’ve developed to avoid risk and rejection. To be spontaneous and free.

Let’s see what we can unleash.

~~~

1. As a research psychologist I am compelled to note that while I find these ideas of Johnstone’s fascinating, to my knowledge they have not been empirically tested and so they are ultimately one man's opinion.

2. I once viewed Dirty Dancing twenty-seven times in a single summer and featured it in my doctoral dissertation, so “random” might not really apply here.

3. Reek, maybe?