We are surrounded by opportunities to help each other. Last weekend I wanted to bring home some croissants from a local vendor. When I got there around 9 a.m. they had already sold out. I commented how popular they were and how the next Saturday I would have to come earlier. My family loved these croissants.

“How many did you want?” asked the counter-server. I told her six. “I’ll prep them and put them in the oven. Can you come back at 1 p.m.?” I went back at the appointed hour and there, already boxed and ready to go, were my croissants.

Rather than be a disappointment to my family, this young woman at the bakery helped me be a provider. The next Friday I called and ordered six croissants for 9 am the next day. Good to her word, the croissants were coming out of the oven, then boxed fresh and hot. I gave her a $5 tip, thanking her for the week before and this. Her response was wonderful. “I would have done this without the tip but thanks. It’s fun serving someone who is so pleasant in the morning. A lot of people are really grumpy. You can ask for croissants anytime.”

Although not being able to buy croissants was only a minor stress, it was alleviated with the help of another person. As a result of making me happy, I came back the next week and her store got my business. In fact, I will probably be ordering croissants from her for a long time.

In contrast, last night my wife Carol and I went to a restaurant where we often have dinner. There was a new waitress, one who seemed to have difficulty doing more than one thing at a time. As a result, we sat for a noticeably long period of time before she even acknowledged us.

From there the evening got worse, culminating in what appeared to be a purposeful neglect of our needs as customers. We chose to not even order dinner.

When we expressed our dissatisfaction and asked for the check, the waitress did not apologize, but instead seemed cross. She rudely threw the bill down on our table and walked away without eye contact or a word. We did not leave a tip, and went elsewhere for dinner.

These stories illustrate how easy we can reduce stress by enhancing success, or increase stress by decreasing a person’s sense of value. In so doing, the croissant-lady-benefactor achieved her own measure of success by becoming a valuable resource to the person she helped. But the rude and disrespectful waitress, along with the establishment for which she worked, was devalued in the same way we had felt devalued. We can alleviate or add to each other’s stress that easily.

So why not be on the stress-reduction end of the relationship? When we help another person, it increases our value. When we feel more valued, our stress goes down. When we have less stress, we can be more productive, and help another person relieve their stress, again enhancing our value. The beneficiary can then use their own reduction in stress to help reduce the stress of another, perhaps even the original benefactor. When I ordered a second batch of croissants, I reduced the potential economic stress of the bakery by purchasing their goods. This would then allow them to stay in business, maintaining the financial well-being of their employees, their suppliers, their landlord, and each of them had the potential to stay in business and provide work for others.

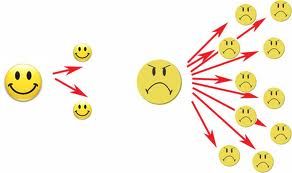

The other important lesson was what the young benefactor said, implying it is a little easier to relieve the stress of a pleasant person. How difficult it can be to maintain a degree of happiness under stress. No croissants! Oh no! But when a person expresses anger, irritability, grumpiness, the behavior influences the response of the other person.

Remarkably, however, even a grumpy person can lighten up when they recognize their stress is about to be relieved. Carol and I would have easily forgiven our overwhelmed waitress if she had just acknowledged what was happening. If she had come over to us and apologized, requesting from us our understanding to relieve her stress, we would have done so gladly. Perhaps she could have asked the more seasoned waitresses to help her, or the bus boy to pour the water or bring the bread. But as she did none of those things, instead our stress increased.

We were not alone. When we complained to another waitress, the people at the table next to us began to complain as well.

They, too, had experienced an unpleasant meal. Overhearing our comments unleashed a torrent of their own. Stress can be bred and spread very quickly when people feel overlooked and undervalued.

When we are known as a person or business that helps relieve the stress of someone else, not only do we help them feel valued, but they begin to develop a trust in our abilities. A trusted person, by default, is a valued person as value leads to trust. So when we relieve another person’s stress we also become a person they can trust.

I ordered croissants Friday night.

I trusted the bakery would have them prepared. That’s how quickly trust can occur. One interaction, one small exchange, and a customer became attached. Being in the business of relieving stress keeps you in business. A philosophy like this is applicable anywhere: at home, at work, and everything in between. And when a whole bunch of people start doing this, imagine what we can get done. Now that’s good business: like offering to make another croissant when they all are gone.