Happiness

Is Color the Key to World Peace?

The nineteenth-century quest for scientific aesthetics.

Posted September 29, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

The nineteenth century was a tumultuous period in French history. Revolutions raged between 1789-1799, and again in 1815, 1830, and 1848. In 1871, the Prussians sieged Paris, and a group of anarchists and radical socialists formed the Paris Commune. Meanwhile, globally, the French struggled to seize and maintain colonial territory through a series of hostile campaigns.

Chaos was the norm, and peace was an elusive dream. Politicians of all sorts clamored for tranquility, claiming that their ideas could calm the choppy waters of war, but they weren’t the only ones seeking solutions to the chaos.

One solution, which emerged during the second half of the nineteenth century, seems odd today, but some philosophers and scientists claimed that it had potential for easing the unrest. That unlikely solution was color.

Scientific Aesthetics

Before we get into why color was a viable solution, I need to introduce the German psychologist Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), who developed a field called “psychophysics.”

According to Fechner, stronger physical sensations produce stronger mental impressions, and vice versa. If I slammed my hand in a door, I would have a stronger emotional response than if it were merely tickled by a feather.

Ultimately, Fechner argued that it was possible to mathematically calculate the relationship between a sensory stimulus and an individual’s psychological response.

If Fechner’s dreams had been realized, I could have gone to my psychologist to uncover the exact emotional toll watching the news would have on me. I could mathematically weigh the benefits, and reach the conclusion that two hours per week is all I can take for optimal mental health.

Fechner’s theories found many adherents, but one of the most fervent was the French polymath Charles Henry, who served as the Director of the Laboratory of the Physiology of Sensations at the Sorbonne.

Based on Fechner’s theories, Henry argued that it was possible to develop what he called “scientific aesthetics.” If science could be used to figure natural laws like gravity and magnetism, Henry asked, why couldn’t it be used to figure out natural laws of perception and beauty?

For example, are there certain shapes that will make people feel inspired? Are there certain colors that will elicit certain emotional states, like serenity? Psychology held the key to understanding the power of aesthetic sensations.

Inhibitory and Dynamogenic Sensations

According to Henry, certain colors, lines, and shapes have predictable and reproducible effects on human emotion. Moreover, all those effects could be distilled into mathematical formulas.

People would no longer stand in front of a canvas and wonder what the artist’s intent was, and artists would no longer wonder how their viewers would react. As long as they stuck to psychophysical laws, everyone would feel the same things and react the same way.

Henry divided sensations into two main categories: pleasant ones and painful ones. Painful sensations require a lot of action from the nerves. Imagine sitting in a quiet room when, suddenly, you’re blasted with a stream of jarring music.

The jolt would likely be painful, not necessarily because you hate the music — although you might. Mostly, the pain comes from the suddenness of the nerves’ reaction. If the noise had been introduced gradually, with a slow, steady rise in volume, it would be more pleasant, even if the music wasn’t to your taste.

Henry called jarring, painful sensations “inhibitory.” In a state of pain, all of a person’s energy is jerked toward a sensation.

Pleasant sensations, which Henry called “dynamogenic,” are continuous. They don’t require as much energy because the nerves aren’t completely shifting gears. You literally feel lighter in a state of pleasure because your body demands less energy to process your emotions.

According to Henry, the way humans experience art, color, and other sensory stimuli is largely depended on the interplay of inhibitory and dynamogenic responses.

Colors and Emotion

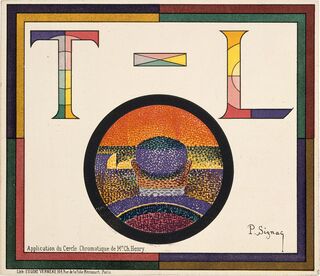

Using all this information, Henry attempted to develop a color circle based on which colors exhausted the eye and which energized it.

Colors that were dynamogenic made people happier, he argued. These were the “warmer” colors with longer wavelengths of light, like red and yellow. Cooler colors like blue demand more energy from the eye.

For a mixed color like green, the amount of happiness or sadness it generated could be determined by its components. Henry concluded that green is a “tiring” color because in order to see it, the ocular nerves have to alternate quickly between blue and yellow, which have radically different wavelengths of light. Orange was a more pleasing color because the switch between red and yellow was much easier on the eye.

Colors not only had the power to conjure happiness, sadness, and disgust. They also had “precise expressive values” and were “linked to the most complicated ideas.” Colors could activate emotions like faith, hope, tranquility, and peace.

Advocates of scientific aesthetics believed that psychophysics would allow the development of art, architecture, and literature that fostered certain emotional responses. Consequently, it would be possible to create a calm, rational world, filled with much less chaos.

Art as the Key to Peace

Henry argued that art could undo the trauma of war and violence. Looking at a painting designed to elicit happiness, peace, and joy, could prevent people from experiencing mental crises, blasting each other with bullets, and tearing the streets apart. Conflict was human, but it could be mediated through color psychology and beauty.

It might sound naïve, and indeed, much of the science has been superseded, but there is something admirable in Henry’s faith in human creativity and resilience. He and his compatriots were dedicated to finding solutions, as improbable as they may seem, to the problems plaguing the world. They refused to fall into the trap of pessimism, instead seeking answers in the beauty and rationality that still existed in the world.

References

Heidelberger, Michael. Nature from Within: Gustav Theodor Fechner and His Psychophysical Worldview. Translated by Cynthia Klohr. ittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004.

Henry, Charles. Introduction à une esthétique scientifique. Paris: Revue Contemporaine, 1885.

Rood, Ogden. Students’ Text-Book of Color; Or, Modern Chromatics, with Applications to Art and Industry. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1881.