President Donald Trump

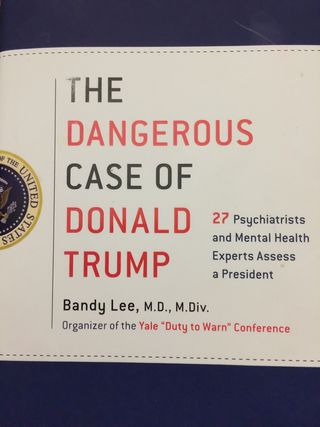

The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump

Should mental health professionals get involved with diagnosing the president?

Posted January 5, 2018

The issue is not really about diagnosis; it is about the professional’s ethical duty to warn. It is about a developed expertise in assessing danger to self and other. I highly recommend this courageous new book edited by Dr. Bandy Lee called The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump that compiles chapters written by prominent and articulate psychiatrists and mental health professionals.

When George W. Bush came into office, I felt a strong sense of dread. I feared that his lack of thoughtfulness and his motivation to war, driven partly by his father issues, pointed to a dangerous situation—as, in fact, the wars in Iraq and Afganistan have turned out to be. I wrote letters to the editor raising the question of danger to self or others, but none were published.

Authors in The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump elaborate on the question of dangerousness by strongly asserting that it is, in fact, an ethical matter of duty to warn. Respecting the Goldwater Rule, or Section 73 of the APA code of ethics, citing the dangers of a malignant society becoming “normalized,” Robert J. Lifton issues a call to action; it is urgent that voices of those who assess danger to self or other must speak up.

Speaking up is, according to Lifton, itself an ethical course of action. He calls this course of action “advocacy research,” that is “combining a disciplined professional approach with the ethical requirements of committed witness, combining scholarship with activism” (Lifton, xviii), what he calls the “activist witnessing professional” (xix). As activist witnessing professionals, we can “bring our experience and knowledge to bear on what threatens and what might renew us.” He makes the point that the public has trust in its mental health professionals they will warn in the case of clear and present danger. And if there are mistakes to be made, they should err on the side of safety.

Herman and Lee take the ethical charge further, asking whether we, as health professionals, are acting in collusion with the state in issues of power, or acting in resistance to them. Herman and Lee consider the duty to warn as a professional responsibility to educate the public. In fact, they know, as professionals, that the situation will become worse as sociopathic and paranoid traits can become amplified over time.

Finally, they uphold as the highest ethical standard: Do no harm. “Therefore, it would be accurate to state that, while we respect the rule, we deem it subordinate to the single most important principle that guides our professional conduct: that we hold our responsibility to human life and well-being as paramount” (p. 12).

They warn: “Collectively with our co-authors, we warn that anyone as mentally unstable as Mr. Trump simply should not be entrusted with the life-and-death powers of the presidency” (p. 8).

The issue of dangerousness

Dangerousness can be assessed without using formal diagnostic categories. Tansey points to Trump’s “attraction to brutal tyrants and also the prospect of nuclear war” (p. 16). Sheehy notes the “pit of fragile self-esteem” that leads to bullying and grandiosity (p. 16). Other terms include these used by Zimbardo and Sword: “condescension, gross exaggeration (lying), jealousy, lack of compassion, and viewing the world through an “us-vs.-them” lens” (p. 26), “childlike need for constant attention” (p. 31). Trump’s delusions and his alternate reality demonstrate a crucial impairment of sanity.

Dangerousness also shows up in our clinical settings, as clients may get triggered by Trump’s resemblance to their abusive fathers, or by his posing existential threats to their ethnic community. Finally, dangerousness can be assessed by the toxic impact on a society: “Trump amplifies and exacerbates a national “symptom” of bigotry and division in ways that are dangerous to the nation’s core principles (p. 18). Mika warns us against the inevitable “downfall” from the “oppression, dehumanization, and violence” of the “toxic triangle” of the “tyrant,” the “his supporters,” and “the society” (p. 19). Zimbardo and Sword describe “the Trump Effect” as the shown by an increase in bullying behaviors, in the schools and between racial and religious groups. In fact, today’s New York Times (17 December 2017), contains an article with a report from the Southern Poverty Law Center showing an increase in events with swastikas, Nazi salutes, and Confederate flags. Given Trump’s access to nuclear power and the power of the United States, Zimbardo and Sword say clearly: "We believe that Donald Trump is the most dangerous man in the world” (p. 47).

And they very reasonably inquire: If the doctrine of Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California 17 Cal. 3d 425 (1976) mandates that we warn potential targets of a threat or potential threat toward them, why shouldn’t we have a duty to warn our fellow citizens in the case of Donald Trump?

If people want to get involved, the best person to contact is John Gartner who heads up the Duty to Warn organization. Here is a direct link to John's online petition.

References

Lee, B. (Ed.) (2017). The dangerous case of Donald Trump. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.