Trauma

The Implications of Poverty, Oversights, and Medication to Childhood Trauma Care

Sending out an S.O.S to help combat childhood trauma.

Posted July 9, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- The types of trauma exposure more closely tied to lower SES and child welfare equate to about 11 of the near 20 categories of childhood trauma.

- Trauma behaviors are in response to the attempts to manage the pain, fear, and distress from the traumatic experience.

- When it comes to our most vulnerable lower SES youth, professionals often misdiagnose and medicate trauma behavior as a mental disorder.

This is Part 2 of a series that addresses childhood trauma and how we can help. In Part 1, I discussed the stats, types, and signs of trauma exposure.

Impact of Poverty

I don't believe what I saw.

Poverty is, if not the primary factor, why we have too many children being traumatized. Children living in poverty or low-income settings and others in Child Protective Services (CPS) or foster care are more likely to experience one or multiple forms of childhood trauma.

When we consider the types and signs of trauma exposure covered in Part 1 of this series, as well as possible higher crime rates, substance abuse, and violence discussed, a triage approach focused on the lower spectrum of socio-economic status (SES) could be beneficial to efforts combating childhood trauma.

Children living in poverty and lower-income communities are more likely to experience trauma in the form of exposure to violence in the community, domestic violence, personal/interpersonal violence, and substance abuse. If a child lives in a home with substance abuse or domestic violence or living in poverty is leading to toxic stress for the family, the youth might also not feel cared for, appreciated, or loved.

Many in poverty don’t have or adequately utilize insurance, so the chances increase that they might have a caregiver suffering from mental illness and not being treated. Meanwhile, emotional abuse might become another traumatic experience. According to clinical colleagues, emotional abuse has historically been among the most insidious and damaging forms of childhood trauma and is often overlooked.

But for those living in poverty, such children, by default, are experiencing poverty conditions. There also is a higher probability their schools and walks to school are more likely not to be as safe as they deserve, and as a result, they might more frequently be bullied or witness school violence.

Please also note that according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Service Administration for Children and Families (ACF), children and families involved with child welfare are disproportionately poorer than the general population, and children in foster care are largely drawn from families living at or below the poverty level.

Thus, most kids monitored by CPS and in foster care are typically exposed to the same levels of conditions and traumatic events as children in poverty and low-income communities. And for kids being taken from their homes to be put in foster care (experience forced displacement), we add on another trauma experience.

The types of trauma exposure more closely tied to lower SES and child welfare (as italicized above) equate to about 11 of the nearly 20 categories of childhood trauma. When we consider the age of these children when the trauma occurs (the younger, the worse impact) and the frequency of incidents (how many times did they experience each of these categories), the probability increases of additional physical and emotional damage due to childhood trauma as well as having caregivers exposed to trauma.

Implications to Child Welfare and Education

Rescue me before I fall into despair.

Reflecting on the signs of trauma I shared in Part 1 of this series, let’s think about the implications that such understandable and justifiable reactions to trauma have on education and the challenges it provides to educators trying to achieve a moment of Zen and make test scores miraculously reach levels of proficiency.

For example, if across urban districts nationwide, a considerable percentage of students in an average classroom have experienced childhood trauma, these signs and symptoms most likely contribute to disruptive student behaviors and feelings or mindsets unbeneficial to a productive learning environment.

These signs and symptoms most likely keep students from focusing or finding lessons of interest. And if the children are not being treated for such trauma, how can we expect educators to be able to teach populations of children who have been traumatized?

Think about the implications of trauma to child welfare. Every child going through CPS or foster care has experienced at least one or four or more categories of childhood trauma. Meanwhile, states only have a handful of programs or providers to support and treat these kids. Most of these service providers are urban-based, leaving rural areas with less access to resources.

What are case and social workers supposed to do when they have limited time due to heavy caseloads? With possibly limited training in how to help traumatized kids and very few places to send the youth for help, and nearly every child they see every day has experienced childhood trauma, what are caseworkers supposed to do?

In many states, my child welfare team applying a VitalChild-VitalClient-focused lens has been told that due to limited-service providers, it could take months for a child to get an appointment with a therapist, clinician, or counselor. This is due to the shortage of providers and the backlog of clients and is challenged further by outdated assessments and technology-driven processes to expedite more efficient care.

The Mistakes and Oversights

Message in a bottle.

But even once children in child welfare and low-income communities are assigned to a mental health practitioner, in many cases, there are a few serious mistakes taking place. And these mistakes start with meeting the professional obligation to ensure diagnostic clarity and accuracy.

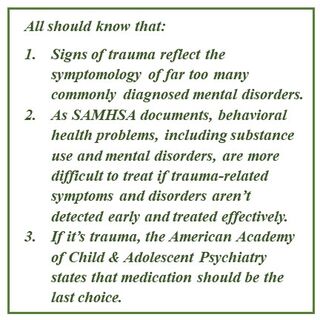

Unfortunately, given the abnormal number of mental disorders foster children are being diagnosed with, and multiple types of psychotropic drugs, too many foster children are being prescribed (i.e., Google “over-medicated foster children lawsuit”), when it comes to our most vulnerable lower SES youth there is a high probability that counselors and clinicians, and most definitely psychiatrists, are too often misdiagnosing concerning trauma behaviors and symptoms to be reflective of a mental disorder. Why?

This is most likely due to symptoms used to diagnose common mental disorders closely reflecting signs of childhood trauma. For example, if a child is displaying reactive behaviors from childhood trauma reflective of anxiety, depression, anger, fear, shame, problems with trust, difficulty concentrating, self-destructive or risky behaviors, and withdrawal, and if trauma was not the clinician’s first concern (aka another oversight), it might be an understandable mistake to diagnose a child with ADHD, anxiety, depression, and several other mental disorders.

But as discussed above, if you are working with a low-income child or a youth in CPS or foster care, why would you not think of and seek to identify and possibly treat trauma first?

Also, due to a misguided ethical belief that mental health practitioners must endorse medicating a client when a mental disorder is identified, too many are taking a medication-guided symptom-by-symptom approach to treatment. Too many mental health practitioners are endorsing or prescribing a collection of powerful mind-controlling brain-numbing drugs to mask or minimize each-and-every symptom of a disorder that a youth hypothetically has.

Therefore, a foster child possibly exhibiting many concerning behaviors, most likely related to trauma, could end up being put on three to a half dozen dangerous medications because they possibly were misdiagnosed with three mental disorders.

Many need to consider that these disturbing symptoms possibly react to trauma exposure. These “symptoms” are reactions to life, a warning sign that someone is unsafe, in trouble, or need of care. Suppressing these trauma symptoms with drugs is like taking the batteries out of a smoke detector. These reactions are coping skills (good or bad) that are the result of an incident or collection of incidents that cause childhood trauma.

I’m Sending Out an S.O.S.

How can we label basic and justifiable reactions to the challenges of a trauma-conflicted life as signs of a latent mental disorder? It’s called being human. But as the black box warnings for nearly every psychotropic drug prescribed share, these drugs come with side effects (which might be better labeled direct effects).

And these “side effects” such as suicidal ideation, worse depression, OCD tendencies, drug addiction, and even overdose and death are often worse than the original symptoms being medicated. When one displays more symptoms due to the side effects accompanied by these psychotropic drugs, it, unfortunately, can lead to a diagnosis of more mental disorders and more meds, a vicious cycle.

Treating trauma first is paramount because, as noted, these behaviors are in response to the attempts to manage the pain, fear, and distress from the traumatic experience. Failing to address such feelings first may simply result in different behaviors emerging to cope with the unresolved pain.

Imagine trying to balance a large water balloon in your hands. Supporting one end only displaces the water to the other side, as you then struggle to contain it.

Failing to effectively address trauma first increases the likelihood of a frustrated client, as they realize treatment is not really fixing the problem. As for child welfare and education agencies seeking to improve levels of care and shorten the duration of services needed, treating trauma first without medication holds great hope.

References

Bruskas, D., & Tessin, D. H. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences and psychosocial well-being of women who were in foster care as children. Permanente, 17(3),131-141. DOI: 10.7812/TPP/12-121

Clarkson Freeman, P.A. (2014), Prevalence and Relationship between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Behavior among Youth Children. Infant Mental Health, 35: 544-554. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21460

Cohen, J.A. (2010). Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Child and Adolescents with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(4), 414-430. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2009.12.020

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Garner, A., & Yogman, M. (2021) COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH, SECTION ON DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS, COUNCIL ON EARLY CHILDHOOD, Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health. American Academy of Pediatrics ,148 (2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052582

Houry, D. "Identifying, Preventing, and Treating Childhood Trauma ." , Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 11 July 2019, www.cdc.gov/washington/testimony/2019/t20190711.htm

NCTSN the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Secondary traumatic stress https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/secondary-traumatic-stress#:….

Peterson, C., et al. (2018). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.018.

Turney, K. & Wildeman, C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences among children placed in and adopted from foster care: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 64, 117-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.009

"Understanding Child Trauma.", Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 22 Apr. 2022, www.samhsa.gov/child-trauma/understanding-child-trauma

Walsh D, McCartney G, Smith M, Armour G. Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019 Dec;73(12):1087-1093. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212738. Epub 2019 Sep 28. PMID: 31563897; PMCID: PMC6872440.