Cognition

How Context Helps Us Understand the Meaning of Words

"You shall know a word by the company it keeps."

Posted June 1, 2021 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

Key points

- Humans often rely on cognitive shortcuts. These shortcuts can sometimes fool us, but they generally help people make sense of the world.

- Cognitive shortcuts are useful in language processing. People can get a good sense of the meaning of a word by looking at its context.

- This helps explain why humans are so good at language processing, which relies on both the human mind and the organization of language itself.

The human mind is astonishing. We can think through the toughest problems and find the smartest solutions. We can compute answers to the toughest mathematical questions. And we can apply our creative skills to produce wonderful pieces of art.

When it comes to processing language, things are equally impressive. We have little difficulty extracting words and sentences out of a long stream of sound bursts, called speech. When it comes to reading, we are able to read some 200 to 250 words per minute, and a skilled reader is able to boost that number to some 300 words per minute. When it comes to the sentence structure, we have little difficulty understanding that the sentence “colorless green ideas sleep furiously” is grammatical (whereas “furiously ideas colorless sleep green” is not).

We are avid language users. We can keep tens of thousands of words in mind and know the relations between them. We understand their meaning and can flawlessly place them in a sentence. And talking about sentences, we can recognize as many sentences as there are grains of sand in the Sahara desert. We are true geniuses.

The scientific literature has shown countless examples of our mental depths. Human cognition is simply so advanced that we would like to place ourselves on top of the hierarchy of species when it comes to intelligence. In fact, we are convinced that we are so smart that we would readily claim we are smarter than all other species. We may not run as fast as a cheetah, swim as fast as a black marlin, be as loud as the sperm whale, or have a sense of smell as strong as the African elephant, but we are certainly smarter. We’re the smartest of all, we think…

When Context Tricks Us

But recent studies show we may overestimate our thinking skills. It turns out that when we make decisions, our thinking is in fact rather sloppy. Let me give a few examples. In the picture below, it is obvious that you see a grey bar in a grey background. The bar starts with light grey on the left and turns to darker grey on the right. Except that what you really see is one single shade of grey in the bar. The context has fooled you in seeing a spectrum of grey in the bar.

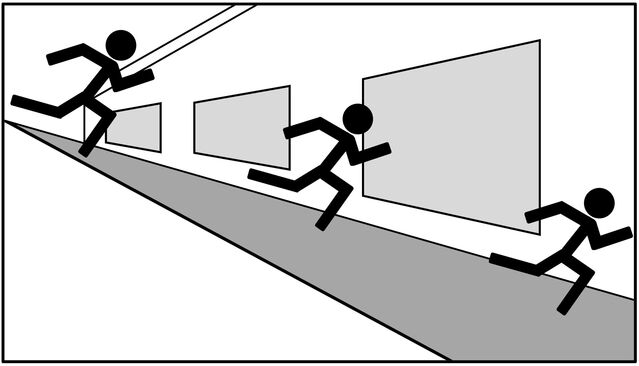

And this is not just true for color perception. In the picture below, you may think you see a giant runner on the left, a tiny runner on the right and a medium-sized runner in the middle. Instead, however, you actually see three runners of identical size. The context of the perspective has fooled you and likely convinces you that the three runners must be of different sizes.

Before you conclude being fooled is reserved for optical illusions, let me give another example by introducing Belinda.

Belinda is 25 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majors in philosophy. She is deeply concerned with issues regarding sustainability, biodiversity and global warming.

What is most likely:

a) Belinda is on the Dean’s list.

b) Belinda is on the Dean’s list and a waitress in a vegan restaurant.

Many will fall for the second answer. The vegan restaurant is obvious. However, in this so-called conjunction fallacy, the context in which the answer could be placed so heavily rests on your mental shoulders that you may choose for the second answer, even though the first answer is simply most likely, always. There are simply more students on the Dean’s list in this world than ones that are both on the Dean’s list and also work in a vegan restaurant.

The grey does not look like a solid grey because of the context; the runners do not look to be the same size because of the context; and the likelihood of Belinda’s activities were tainted by the context. In most cases, however, it is not at all a bad thing that we are fooled by optical illusions in which the context leads us astray. In fact, we are fooled in a small number of cases, whereas context generally helps us to understand the world around us. When it comes to cognition, context matters a lot. And by relying on context, we can allow ourselves to take cognitive shortcuts.

How We Use Cognitive Shortcuts to Understand Language

This brings me to my favorite topic of language processing. We could ask ourselves the question of how we are able to keep the meanings of those 60,000 words in mind and how we are able to recognize sextillion sentences. Is it because we have such incredible memory storage? We have such incredible brain power? Or might there be something more trivial? Might it be that we take cognitive shortcuts relying on context?

When it comes to the meaning of the word, we may be able to guess it purely on the basis of content. J.R. Firth in the 1950s stated, “you shall know [the meaning of] a word by the company it keeps.” What he meant was that by taking into account the neighbors of a word, we can get a good estimate of what the word means, even though we may have never heard the word before. When I say “my daughter was ferliamated when she heard she would get a puppy,” you get a pretty good sense of the word “ferliamated,” despite never having heard the word before (to my knowledge it does not occur in any English dictionary). Yet you do know what grammatical class “ferliamated” belongs to and can guess its meaning. When we look further into the question of how we are able to keep 60,000 words in mind and can recognize some sextillion sentences, as many sentences as there are grains of sand in the Sahara desert, the answer probably lies in the context.

In a way, we could then argue that language creates meaning. Language provides us with a convenient cognitive shortcut so that we do not have to hold the 60,000 meanings and sextillion sentences in mind. All we need to do is understand some words and the context helps us out with the rest. Even though language users can talk about anything at any time in any context, it seems more likely that they talk about the things whose meaning lies in the same context. This offers exciting avenues for our understanding of the human mind and the way we understand language for it does not only place the burden on the human mind, but also on the organization of the language system itself.

References

Chater, N. (2018). The mind is flat: The illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind. Penguin UK.

De Waal, F. (2016). Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are? WW Norton & Company.

Firth, J. R. (1957). Papers in linguistics 1934–1951. Oxford University Press

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Louwerse, M. (2021). Keeping those words in mind: How language creates meaning. Prometheus Books.