Motivation

Replacing the Pyramid of Needs with a Sailboat of Needs

A bold new book provides an updated version of Maslow's theory of needs.

Posted December 22, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

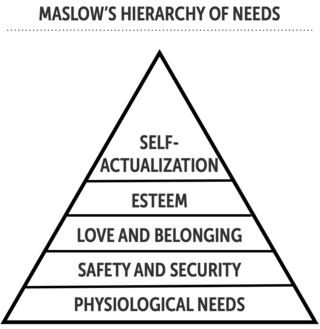

Maslow’s Pyramid of Needs is undoubtedly one of the most iconic psychological images. Reprinted countless times, the pyramid depicts physiological needs such as breathing, food, and water at the base of the pyramid. The next layer is safety and security, then comes love and belonging, then self-esteem and respect, with self-actualization at the top.

Once you’ve seen it, the idea of a pyramid of needs sticks with you. It is intuitive, it is memorable — and it is wrong. As an image of human needs, Maslow’s Pyramid of Needs is mistaken on two accounts: It’s not Maslow’s pyramid. And the needs don’t form a pyramid.

First, rather surprisingly, Abraham Maslow himself never created a pyramid of needs. Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1908, Maslow is still regarded as one of the most influential twentieth-century psychologists who is indeed especially famous for his theory of human needs. Reacting to the atrocities of WWII, Maslow wanted to develop a psychology of human potential, the good in each of us, and what humans ultimately need to flourish.

However, the shape of a pyramid is nowhere to be found in Maslow’s writings. It was a bunch of management scholars who in the late '50s and early '60s drew the pyramid as a mnemonic for managers wanting “maximum motivation at the lowest cost.” The pyramid, thus, does not have anything to do with Maslow himself but rather the iconic shape spread through management textbooks and business consultants eager to sell the pyramid as a tool to extract motivation from unsuspecting employees.

Second, the scientific community realized already decades ago that while humans certainly might have psychological needs, these needs don’t arrange themselves into a clear hierarchy. Furthermore, the list of needs provided by Maslow has been challenged by newer, more empirically supported theories.

In a bold new book, Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization, psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman aims to make Maslow relevant again by retaining the healthy core of his theory while integrating his ideas with the developments of empirical psychology that have taken place in the five decades since Maslow passed away in Menlo Park, CA, on June 8, 1970, when his eager writing to revise his theory came to an unfortunate halt through a fatal heart attack.

Kaufman argues that the part of Maslow’s theory that has stood the test of time is a distinction between two types of needs. First, there are the deficit needs, which dominate our motivation and trump any higher needs when they are urgently lacking. If I am underwater and start to be out of oxygen, self-realization is not the first thing on my mind. The only need I care about is the necessity of being able to breathe again. The more precarious a physical need becomes, the more it preoccupies our minds. Hunger is a powerful motivation. However, as long as my access to water, food, and shelter feel secured, I don’t think about them much. The deficit needs thus become activated mainly when we are lacking them.

Human existence, however, is not mere passive reactance to deficits. As the movie character Solomon Northup memorably states in 12 Years a Slave: “I don’t want to survive. I want to live.” We humans are not mere survival-machines, but active and growth-oriented, eager to take on challenges through which to manifest our full potential. A human being has a tendency for self-fulfillment, “to become actualized in what he is potentially," as Maslow put it.

In this quest to realize ourselves, we are guided by what Maslow called growth needs. While deficit needs are driven by fears, anxieties, and a push to quench what we are lacking, growth needs pull us towards what we find intriguing and valuable. They are the sources of intrinsic fulfillment we are drawn towards when we don’t have to worry about mere survival.

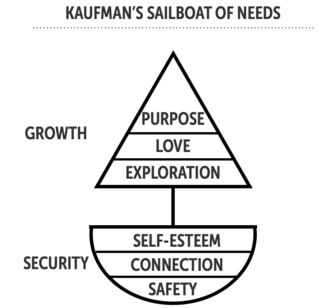

The pyramid fails to capture this fundamental distinction between deficit and growth needs. In its place, Kaufman proposes a sailboat. Life isn’t a project or a competition; it is a journey to travel through “a vast blue ocean, full of new opportunities for meaning and discovery but also danger and uncertainty.” The hull of the boat is what keeps us afloat, offering security from the waves. It represents the deficit needs essential for survival. Kaufman proposes three such needs: feeling safe, feeling that we belong and are not being rejected by others, and protecting our self-esteem. In other words, we need to feel safe both in the physical realm, in the interpersonal realm, and in our relation to ourselves.

But having a protective body is not enough for real movement. Kaufman quotes Seneca: “If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favorable.” What we need to do is to open our sail and dare to embrace life and direct our efforts towards actualizing ourselves.

As for the growth-oriented needs, Kaufman again proposes three: exploration, love, and purpose. We explore our environment for the sheer pleasure of it, we want to feel a deep sense of connection and love with others, and we seek goals worth pursuing to energize our activities. The growth needs are thus not depicted as a pyramid to climb; they are ultimately about opening up to life, daring to treat life as a quest.

Of course, the stronger the hull, the easier it is to boldly open up the sails. To dare to explore and grow, we need to have a secure base. That’s why Maslow wanted to democratize the opportunity to live a growth-oriented life by removing the obstacles for it, like material scarcity, emotional coldness, and institutions crushing our dreams. The needs can be used to evaluate our current institutions like schools, workplaces, and whole societies. When designing and critically examining them, we should be asking are they helping us to satisfy our needs or rather the main reason our needs are thwarted. If the latter, they should be revised. Each of us should be given an equal opportunity to pursue our liberty, and this happens only if our institutions provide safety, security, and a sense of belonging.

This is the legacy of Maslow worth fighting for: to build a culture and institutions that support the ability of each of us to grow and become the best versions of ourselves. This is done by ensuring that as many as possible can grow up, live, and work in environments that support the satisfaction of our basic psychological needs.

References

Bridgman, T., Cummings, S., & Ballard, J. (2018). Who Built Maslow’s Pyramid? A History of the Creation of Management Studies’ Most Famous Symbol and Its Implications for Management Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 18(1), 81–98.

Kaufman, S. B. (2020). Transcend: The new science of self-actualization. TarcherPerigee.

Wahba, M. A., & Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15(2), 212–240.