Anxiety

Separation Anxiety

The damage that taking children from parents can cause.

Posted June 19, 2018

I awoke to the sound of children crying, sobbing, and begging for their parents. This morning, I guess that a lot of us who have newsfeeds for alarms, have had a similar experience. Oddly enough, the crying for their parents somehow managed not to be the only disturbing sound in the sequence—but I’ll come to that other part in a minute. If you haven’t heard it: This is the noise that some of the 2000 children—some of whom are toddlers–make when they are forcibly separated from their parents at the Mexico/USA border by immigration officials.

Children taken away are held for an average of 51 days at an Office of Refugee Resettlement before finding a sponsor in the USA.1 I’m sure that they are fed, clothed, and sheltered. However, this does not constitute the limit of a child’s needs. This should not be news, and there really should be no confusion about this. The effects of deprivation of attachment—because that is what we are talking about here and that’s what you have been listening to–is one of the most heavily researched areas in behavioral science. Furthermore, we have an integrated picture of its effects from comparative biology, neuroscience, genetics, developmental psychology, and psychiatry. We know what happens to separated children in the short, medium, and long terms. None of it is pretty.

So—let’s warm up by starting with something that is pretty.

What is cuteness for?

Have you ever wondered why so many baby animals are cute? And not just cute to us—cute to other animals who are not even their parents, or even their species?2 This cuteness has a technical term—altriciality. And we can measure it. Large head in relation to the body. Large eyes in relation to the head. Small mouth. Squashed-in features. Prominent brow. It is a set of features that elicit caregiving (along with that "aw" feeling) in parental members of the species. And sometimes of other species.

The technical term for such signals is “releasers”3 and the fact that many of the cuteness ones are shared across all mammals (and some other classes of animals) tells us something important: It’s a very old set of mechanisms. At least 100 million years old from when we shared an ancestor. That’s deep in us. Deep in us, before we even became us. This predates humans by a very long time. Our response to child helplessness--and the resultant care-giving responses--are built right in. Like any other instinct they can be turned off--but I'll come to that presently.

Love and trust are inseperable

Mammals vary in the amount of helplessness they show. For example, a baby horse can run within minutes, a baby human takes several years. But—for all mammals—it's built-in deep that they need parental care. All mammals are to some extent social, and we are the most social of them all. To build that sociality, the young of each species—but most especially our species–need someone they can trust.

This may be common sense (although I’m starting to wonder how common it is) but in any case, scientists didn’t always know this. In the early days of psychology, the two dominant theories of child attachment were the behaviourists and the Freudians.4 Both of them got child attachment equally wrong. The two schools of thought were in (incorrect) agreement that the love children had for parents was “cupboard” love—arising from a primary need to be fed. It turns out that the cupboard love theory is simply wrong, and not just with humans. All mammals have a primary need for love from a trusted caregiver. And this is over and above the needs for food, shelter, and the rest. The evidence for this came from two sources to begin with, but over the years we have confirmed it to a degree almost unparalleled in behavioral science.

The effects of deprivation of love on child development

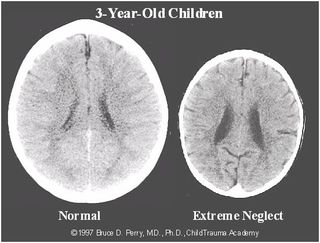

If there is anything close to being an axiom in developmental psychology it would be this: Children need love. Love is not some enjoyable add-on to life. The absence of love produces measurable effects immediately on a child. In the medium to long-term neglect can cause effects so profound that they are visible to the naked eye.

These are brains showing the effects of extreme privation—a child with no social interaction whatsoever for years. But well before we get to that stage, we can observe serious emotional and behavioral damage. What were the two sources of our knowledge about this that I mentioned? One was a (behaviorist) scientist called Harry Harlow, who accidentally undermined the behaviorist take on attachment with a series of famous experiments on social primates. 6 The second was John Bowlby, a Freudian who found evidence to undermine Freud’s version of the cupboard love theory.7

Harlow and the rhesus monkeys

It belongs to only a few behavioral scientists to conceive of an experimental demonstration so iconic that a single picture gives a sense of the discovery. Harlow has that distinction. Raising Rhesus monkeys with surrogate mothers—some of whom delivered milk and some who were soft to the touch he put paid to the idea of “cupboard love” forever. When stressed, where would the young monkey go for comfort? Every time, it was to the soft cuddly “mother.”

Harlow had discovered the need for contact comfort in mammals. Put simply: Cuddling those we trust. If we don’t have it, we get unwell. Some of Harlow’s later experiments got even more gruesome. Surrogate “mothers” who rejected their offspring with blunted spikes or compressed air blasts. The baby rhesus monkeys would keep trying to get comfort from these rejecting surrogates and the constant rejection eventually drove them insane. If these damaged infants eventually became parents themselves, they would pass on this brutality to their own offspring:

"Not even in our most devious dreams could we have designed a surrogate as evil as these real monkey mothers were. Having no social experience themselves, they were incapable of appropriate social interaction. One mother held her baby's face to the floor and chewed off his feet and fingers. Another crushed her baby's head. Most of them simply ignored their offspring.”

Bowlby and affectionless psychopathy

So—that’s one strand of evidence of the need for love in primates—of which we are one. What about direct evidence from humans? In this case, a major figure is John Bowlby. A Freudian by training, he became dissatisfied with the Freudian explanations of child attachment as cupboard love. In his clinical practice, he had documented dozens of delinquent boys who had all gone through some degree of maternal deprivation—separation from the mother during a critical period of childhood. In its most extreme form, these responses could amount to what he called “affectionless psychopathy,” and violent behaviors such as fighting, theft, and arson. Bowlby’s emphasis was on the mother-child dyad, and our later research has expanded this to include fathers and other caregivers. But, he had the essence of the idea: A child needs trustworthy bonds to fully develop socially.

Day care...and lack thereof

Later research has focussed on the effects of much more limited separation of a child from a trusted-care giver in daycare. The effects of this are nothing like so profound as what Bowlby (or, god-forbid, Harlow) showed. But, even here, measurable social effects like aggression and depression (mostly short-term) are detectable in many children who undergo prolonged separation from their caregivers. And daycare is just that: Care for a day. The parent (or parents) are back at the end of that day. They are not pulled apart for weeks or months, or even for good, and in threatening circumstances. People in daycare centers, well—they care.

Which brings me neatly to the other disturbing sound in that clip. The sounds of children experiencing the early stages of deprivation are distressing enough. Those sounds are designed to be distressing—millions of years of evolution have made children’s sounds of distress hard for normal humans to ignore. And this is for the obvious reasons that I started off by mentioning. Small humans are terribly fragile, and obviously needy. That’s why I found the other sound in the clip in some ways more distressing still. Play it again if you need to (and can stand it). I’m sure they are not all like this (please gawd, tell me I’m right about this) but at one minute in that’s the sound of a border patrol agent laughing at the distress, and saying “What an orchestra, I guess they need a conductor”. Hilarious. That’s not someone I would trust to leave anyone’s child in the care of.

References

2) Zeveloff, S. I., & Boyce, M. S. (1982). Why human neonates are so altricial. The American Naturalist, 120(4), 537-542.

3) Tinbergen, N. (1948). Social releasers and the experimental method required for their study. The Wilson Bulletin, 6-51.

4) Freud, A. (1946). The psychoanalytic study of infantile feeding disturbances. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 2(1), 119-132.

5) Perry, B. D., & Pollard, R. (1997, November). Altered brain development following global neglect in early childhood. In Proceedings from the Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting (New Orleans).

6) Harlow, H. F., & Suomi, S. J. (1974). Induced depression in monkeys. Behavioral Biology, 12(3), 273-296.

and

Suomi, S. J., Eisele, C. D., Grady, S. A., & Harlow, H. F. (1975). Depressive behavior in adult monkeys following separation from family environment. Journal of abnormal psychology, 84(5), 576.

7) Suomi, S. J., Eisele, C. D., Grady, S. A., & Harlow, H. F. (1975). Depressive behavior in adult monkeys following separation from family environment. Journal of abnormal psychology, 84(5), 576.

8) Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health (Vol. 2). Geneva: World Health Organization.

9)

Belsky, J., & Rovine, M. J. (1988). Nonmaternal care in the first year of life and the security of infant-parent attachment. Child development, 157-167. Even good quality day care produced attachment issues—such as higher levels of aggression to a measurable degree.

Belsky, J., Melhuish, E. C., & Barnes, J. (Eds.). (2007). The national evaluation of Sure Start: does area-based early intervention work?. Policy Press.

For those who really want to deep dive into some the studied effects of day care:

Ainslie, Ricardo (Ed.). THE CHILD AND THE DAY CARE SETTING: QUALITATIVE VARIATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT. New York: Praeger Press, 1984.

Belsky, Jay and Lawrence Steinberg. "The Effects of Day Care: A Critical Review." CHILD DEVELOPMENT 49 (1978): 929-949. Bredekamp, Sue (Ed.). DEVELOPMENTALLY APPROPRIATE PRACTICE. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1984.

Clarke-Stewart, Alison and Greta Fein. "Early Childhood Programs." In M. Haith and J. Campos (Vol. Eds.), HANDBOOK OF CHILD PSYCHOLOGY VOL. 2: INFANCY AND DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOBIOLOGY. New York: Wiley, 1983.

EARLY CHILDHOOD RESEARCH QUARTERLY, vol. 3, nos. 3 and 4. (Special Infant Day Care Issues.)

Phillips, Deborah. QUALITY IN CHILD CARE: WHAT DOES RESEARCH TELL US? Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1987.

Roupp, Richard, J. Travers, F. Glantz, and C. Coelen. CHILDREN AT THE CENTER: FINAL RESULTS OF THE NATIONAL DAY CARE STUDY. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates, 1979.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. CURRENT POPULATION REPORTS SPECIAL STUDIES SERIES P-23, NO. 129. "Child Care Arrangements of Working Mothers." June 1982: p. 18.

U.S. Department of Labour, Bureau of Labour Statistics. MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW. December 1984: pp. 31-34.