President Donald Trump

The Dunning-Kruger President

How did a psychology term become a partisan trending topic?

Posted January 21, 2017 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Try Googling "The Dunning-Kruger President." New York magazine, Salon, and Politico have recently published articles on that theme. They're referring to Donald Trump and to the Dunning-Kruger effect, a psychological principle that is becoming a lot better known recently.

Named for Cornell psychologist David Dunning and his then-grad student Justin Kruger, it describes the observation that people who are ignorant or unskilled in a given domain tend to believe they are much more competent than they are. Thus bad drivers believe they're good drivers, the humorless think they know what's funny, and people who've never held public office think they'd make a terrific president. How hard can it be?

Dunning and Kruger documented this effect in a number of quantitative contexts. Its first publication, in 1999, bore the memorable title, "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments." The authors observed that you need skill and knowledge to judge how skilled and knowledgeable you are. A tone-deaf singer may be unable to distinguish her talent from that of the greatest stars. Why then shouldn't she believe she's their equal?

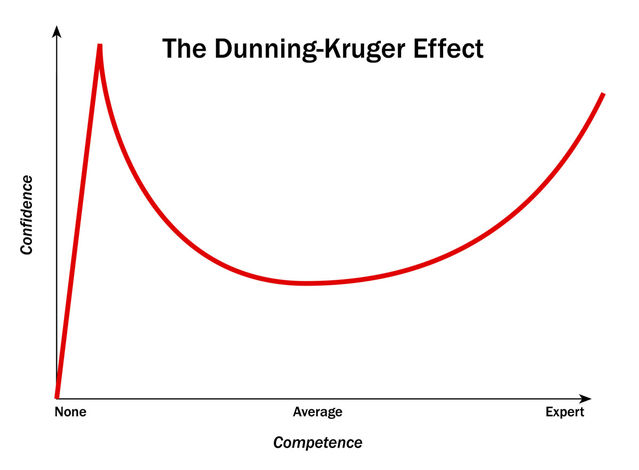

Dunning and Kruger are responsible for one of my favorite charts. It tracked competence versus confidence. When you have no expertise whatsoever (far lower left), all rational souls recognize that. As Dunning and Kruger put it, "most people have no trouble identifying their inability to translate Slovenian proverbs, reconstruct a V-8 engine, or diagnose acute disseminated encephalomyelitis."

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. Those who have the slightest bit of experience think they know it all. That's the peak at upper left. Then, with increasing experience, people realize how little they do know, and how modest their skills are. Perceptions reach a minimum (center of chart), then slant upward again. Those at the level of genius recognize their talent, though still tend to lack the supreme confidence of the ignoramus.

The chart is almost a emoticon—a smile turned smirk.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is not a pathological condition; it is the human condition. You may not harbor illusions about your ability to be Commander in Chief or devise a brilliant health-care plan. Yet in dozens of quieter ways, we all suffer from an incurable delusion of competence.