Education

A Bad Sign for the Future of Higher Education

What happens when universities deem opinions "harmful"? The case of Ilya Shapiro

Posted July 25, 2022 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- To thrive in a pluralist, liberal democracy, we must be capable of withstanding the discomfort of opinions with which we disagree.

- Ideological monocultures breed certitude, intellectual hubris, and a lack of curiosity—mental habits that lead to feeling harmed by opinions.

- Psychological well-being requires recognizing the difference between harm and discomfort.

- The less willing we are to withstand discomfort, the more we will feel harmed.

Psychological well-being requires recognizing the difference between discomfort and harm. To thrive in a pluralist, liberal democracy, we must be capable of engaging with people who hold opinions we oppose and withstanding the discomfort of their insensitively phrased statements (and even comments we find offensive) without feeling harmed by them. The less willing we are to withstand discomfort, the more we will feel harmed. The more we focus on how harmed we feel rather than the content of arguments, the less persuasive we will be.

Georgetown University's recent treatment of conservative legal scholar Ilya Shapiro (which earned it a spot on FIRE’s 2022 Worst Colleges for Free Speech list) is case in point. Not only are Georgetown’s actions troubling indicators of the state of campus free speech and the future of higher education more broadly, they entrench its campus ideological monoculture, increase interpersonal distrust, and reduce the already limited ability of those on campus to differentiate between unpopular opinions and actual harm. None of this bodes well for developing persuasive counterarguments or for mental health on campus.

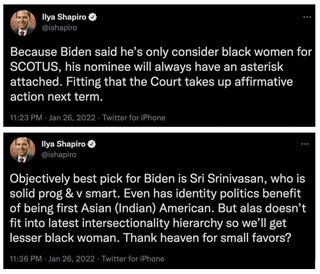

In January 2022, before his first day as Executive Director of Georgetown University’s Center for the Constitution, Shapiro “inartfully” (as he later admitted) tweeted criticism of President Biden for announcing that only black women would be considered for the Supreme Court.

Shapiro argued that Biden’s decision unnecessarily opened the question of whether the eventual nominee would have been chosen if she were in competition with jurists of all other identities. She would “always have an asterisk attached,” he wrote. This concern resonated with many on both sides of the aisle who would have preferred Biden to declare that his choice would be the most qualified jurist regardless of identity—and then nominate a black woman.

The “objectively best pick,” Shapiro claimed, would be a very smart, “solid progressive” named Sri Srinivasan. Noting that Srinivasan, the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and an immigrant from India, would be the “first Asian (Indian) American” on the Court, Shapiro complained that limiting the search to a different specific combination of race and sex disqualified Srinivasan. Therefore, he tweeted, “we’ll get a lesser black woman.”

When a protest erupted, Shapiro quickly deleted his tweets and apologized, clarifying his intention to convey that “nobody should be discriminated against for his or her skin color.” For many on the left, his poor choice of words obfuscated that message. But for others, his insensitively worded statements still clearly conveyed his opinion that any nominee, irrespective of race or sex, would be a “lesser” jurist.

Regardless of how innocent the intention, the phrase “a lesser black woman” was ill-considered, tactless, and unwise. William Treanor, dean of Georgetown Law, had the opportunity to say exactly that and put the matter to rest. Instead, however, he suspended Shapiro, subjecting him to a lengthy investigation while proclaiming that his tweets were “antithetical to the work that we do here every day to build inclusion, belonging, and respect for diversity.”

This saga illustrates three common campus issues, all of which negatively affect mental health.

The first is that campuses have become tribal moral communities. Moral virtue is now signaled by expressing outrage and contempt toward ideological opponents rather than compassion and curiosity. Apologies are received as confessions of guilt. Offering forgiveness can indicate insufficient moral purity. And particularly for those whose identity is intertwined with ideology, using the principal of charity to interpret the words of ideological opponents is now taboo.

Given this ethos, Shapiro’s comments were interpreted by ideological opponents on campus in the least charitable light. Student groups protested, faculty complained, and petitions were circulated. The university’s official report claimed that Shapiro had “categorized Black women as ‘lesser.’” The dean publicly reprimanded Shapiro for his “appalling use of demeaning language,” even accusing him of suggesting that “the best Supreme Court nominee could not be a Black woman.”

Second, it is now a regular feature of campus discourse to conflate opinions with harm. The question of whether identity should constitute the primary qualification for a job ought to be a matter of debate, as should whether affirmative action is beneficial or detrimental. But instead, “wrong” answers to such questions are considered “harmful” and classified as “microaggressions.”

Dean Treanor circulated a letter at the conclusion of the investigation announcing that although Shapiro would not face sanctions, his tweets were “harmful to many in the Georgetown Law community and beyond.” Even more troubling, the Georgetown University Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity and Affirmative Action reported that the school would take “appropriate corrective measures” to “prevent the recurrence of [Shapiro’s] offensive conduct based on race, gender, and sex,” and warned that even one “similar or more serious remark,” would be so harmful that he could credibly be accused of creating “a hostile environment.”

Third, ideological monocultures breed certitude, intellectual hubris, and a lack of curiosity. The fact that universities are largely composed of left-of-center thinkers contributes to an unwillingness to consider the views of right-of-center thinkers and even a tendency to demonize them. When a university shields students (and faculty) from politically unpopular points of view, it abandons its mission of truth-seeking and knowledge production and ceases to encourage the intellectual virtues of curiosity, open-mindedness, and intellectual humility.

The charges against Shapiro were eventually dropped, but only because his tweets had been posted before his Georgetown start date. As a result, on June 6, Shapiro resigned. “The university didn’t fire me,” he wrote, but it “abandoned free speech” and “created a hostile environment.”

For a law school to fulfill its mission—and for our country to be a nation of laws—lawyers must, at a minimum, be capable of understanding the legal reasoning of scholars and jurists with whom they disagree. In 2014, Professor Nicholas Quinn Rosenkranz noted that he was one of only three openly right-of-center law professors at Georgetown, making the ratio of left-to-right faculty roughly 40 to 1. That ratio, he says, is at least as bad today.

Supporting the addition of a conservative legal scholar would have offered students the opportunity to discuss SCOTUS cases and rulings with someone who not only understands the current court’s legal reasoning but is willing to make the best arguments in its defense. But as Rosenkranz wrote years ago, “at Georgetown, the consensus seems to be that three [right of center professors] is plenty—and perhaps even one or two too many.”

Pamela Paresky, PhD, is a 2022-23 Visiting Fellow at the Johns Hopkins SNF Agora Institute, a Visiting Senior Research Associate at the University of Chicago's Institute on the Formation of Knowledge, a Senior Scholar at the Network Contagion Research Institute, and the author of the guided journal, A Year of Kindness. Dr. Paresky's opinions are her own and should not be considered official positions of any organization with which she is affiliated. Follow her on Twitter @PamelaParesky, and read her Newsletter at Paresky.Substack.com.