Ethics and Morality

There's Plenty Worth Standing Up For

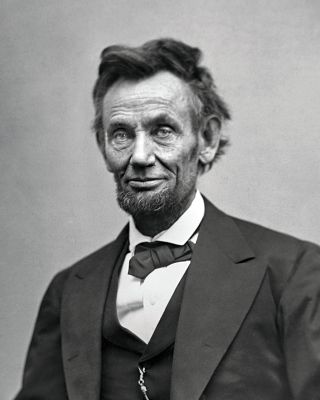

America's great poet, Abraham Lincoln, had more than mourning in mind.

Updated November 17, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- This year marks the 160th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address.

- Lincoln was battling slavery, but he was also fighting for truth and goodness.

- Lincoln's words illuminate what about the United States matters most.

November 16, 1863, was a great day in American history—not because a decisive battle was fought on this date, but because Abraham Lincoln, arguably one of the great poets of America, paused to reflect on the meaning of one of the greatest battles in American history. Fought over three days, the Battle of Gettysburg precipitated both 50,000 casualties and the beginning of the end of the Civil War, a conflict that Lincoln believed was being fought over the nation’s greatest scourge, slavery.

In Lincoln’s memorable words, could a nation “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” endure? So momentous was the question that, over the course of the war, three-quarters of a million soldiers would give their lives. Lincoln called upon the living to ensure that the fallen had not died in vain and that “government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth.”

His call rings as true today as it did 160 years ago because the United States still has unfinished work. We are no longer fighting an internecine war, yet the nation remains deeply riven by issues such as abortion, gun control, and free speech. Is abortion defined by women’s rights or the rights of the unborn? Which is paramount, the right of citizens to arm themselves or the reduction of homicides and suicides? Does the First Amendment protect all speech or only that which a majority of citizens find acceptable?

There are no easy answers, and some would say that the situation is hopeless, that consensus will never be reached, and that the nation will remain permanently fractured. Yet underlying the questions of correct and incorrect and right and wrong is an even deeper challenge—namely, to preserve and promote a culture in which the lively interchange of differing opinions is not only tolerated but prized, not so much as a right not to be infringed but as a path to mutual enlightenment.

Only a lover of words and ideas, someone who believed in the power of reasoned dialogue and contentious discourse, could have produced such seminal works as the Lincoln side of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, the Second Inaugural Address, and, yes, the Address at Gettysburg. Said Lincoln, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believed this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free... It will become all one thing or all the other.”

Lincoln believed that words and ideas are meant to clarify, deepen, and inspire understanding, not to obfuscate, manipulate, bamboozle, or induce a state of nihilism and despair. He reminded his fellow Americans that none of us can escape history, that even the choice to opt out of the conversation and remain silent inevitably bears profound moral consequences, and that what perishes and what persists on Earth is, to a remarkable degree, up to us.

Lincoln wrote that he took the oath of office to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution and that he could neither “take an oath to get power” nor “break that oath in using that power.” He believed that his preternatural gift for the English language had been given to him to serve some higher purpose. Battling periods of what we would call major depression throughout his life, he was saved by the conviction that he might be of service to others and to the nation.

To be sure, words and ideas can be seen as tools, but they ought to be understood as instruments not of tyranny but liberation. When Lincoln said at Gettysburg, “We cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground,” he was drawing attention to the poverty of words as compared to actions, the “last full measure of devotion” of those who had died there. Yet he was also invoking a higher standard of truth and reminding his listeners that man is not the measure of all things.

It was not mere window dressing when Lincoln said, contemplating the continuation of the bloodiest war in U.S. history, that if God wills, “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago so it must be said, ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’” He called for “malice toward none,” “charity for all,” and “firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right.”

The question for Lincoln was not whether there are real standards of good and bad, right and wrong, and justice and injustice, but whether we human beings can, in our own age, discern them. The greatest threat to the nation and its unprecedented democratic experiment, as he saw it, was not spirited dispute or even armed conflict but surrendering to a far more insidious foe, the notion that words have somehow been rendered meaningless and ideas obsolete.