Relationships

How Martin Luther King Jr. Disarmed His Critics

The "Letter from Birmingham Jail" is 60 years old.

Posted April 16, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail" was published April 16, 1963.

- King was responding to an open letter from eight local clergymen calling on protesters to be patient and obey the law.

- King manages to defeat his opponents' arguments in a conciliatory and hopeful manner.

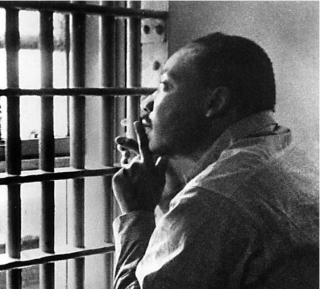

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which is both a foundational document in the history of the American civil rights movement and one of the most influential documents ever composed by a political prisoner. King’s letter also serves as a highly instructive and beautiful example of how to respond effectively to criticism, exposing the weaknesses in an opponent’s argument while simultaneously fostering civility and building rather than destroying relationships.

King’s missive was prompted by an open letter from eight local clergymen that offered several criticisms of the peaceful protests then taking place in the highly racially segregated city of Birmingham, Alabama. First, they lamented that “outsiders” were responsible for the protests. Second, they accused protesters of resorting to “extreme” measures that promoted hatred and violence. Third, they urged their fellow citizens to adopt a more patient approach, allowing time for “law and order” and “common sense” to prevail. Finally, they accused the protesters of breaking the law.

King read their letter in a jail cell, and the conditions of his confinement were so harsh that he lacked even paper on which to pen a response. Initially scribbling in the margins of the local newspaper in which the clergymen’s letter had been published, he transitioned to scraps of paper before he was finally given a proper pad of paper by his attorneys. From his very first words, King adopts a conciliatory tone. He addresses his opponents as “my fellow clergymen,” thereby reminding them that, despite their racial differences, they are linked by a more fundamental bond of faith.

King first addresses the criticism that he is an outsider. As president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he is in Birmingham at the request of the organization’s local chapter, one of 85 throughout the south. Having promised to provide support to any chapter that found it necessary to adopt a nonviolent direct-action campaign, King and his colleagues are merely abiding by their pledge. Moreover, he says, he is in Birmingham because “injustice is here,” placing him in a tradition of reaching out to the oppressed that includes the Old Testament prophets and the apostle Paul.

King reminds the pastors that they and he are not just citizens of Birmingham and Atlanta. They are also citizens of the United States and fellow children of God. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” he writes. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere in this country."

The demonstrators employed highly effective means to evoke this sense of kinship and shared responsibility. They were well dressed and conducted themselves in a peaceable and orderly manner, including in their efforts both teenagers and children. When footage of the protests was broadcast on national television, viewers could not fail to be struck by the stark contrast between the peaceful conduct of the protesters and the violence of the municipal authorities, which included the use of high-pressure fire hoses and police dogs.

To the charge of extremism, King responds by outlining four steps in a nonviolent campaign, including collecting facts concerning injustice, negotiation, self-purification, and direct action. Birmingham, he asserts, is the site of more unsolved racial bombings than any city in the nation. Local leaders had previously agreed to remove “whites only” signs from businesses but failed to deliver. The protesters had trained themselves to respond to blows without violence. King and his colleagues could see no alternative to applying additional pressure on authorities through direct action.

Nor can King abide the charge of excessive impatience. He admits that the protesters’ actions will lead to a crisis, but the cause of justice demands nothing less. Without “creative tension,” people will ignore the issue, and authorities will continue to refuse to negotiate in good faith. “Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor,” leaving the oppressed no recourse but to demand it. He reminds his critics that blacks had already waited 340 years for their “constitutional and God-given rights” to be respected—hardly a sign of impatience.

King is most effective in describing the effects of segregation on its victims. He asks his fellow pastors to imagine what it is like “when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see the tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky.”

King breaks down a wall of separation by reminding his critics that they are all parents and that they share a common mission of explaining to their children why the world they are inheriting works as it does. How would they, men of the cloth, explain to their own children that some children are, simply because of their race, inferior to others and deserving of oppression? Where in their shared sacred scriptures, which emphasize that all human beings are children of the same God, would they find justification for instilling a sense of “nobodiness” in one set of human beings?

To the charge of lawlessness, King responds by appealing to a higher law. There are, he says, both just and unjust laws, and no just person is bound to obey the latter. Only laws that square with the moral law and the law of God are just. When a law is inflicted by a majority on a minority and does not bind the members of the majority, it is unjust. When a supposedly democratic government enacts a law, yet even in majority-negro counties not a single black is registered to vote, the law is unjust. A law that prohibits peaceful protest cannot be squared with the higher law of the First Amendment.

In the end, King pleads guilty to the charge of extremism, though not as his critics intend. When it comes to the fight against oppression, extremism is no vice. In fact, the early Christians, he writes, were universally recognized as “disturbers of the peace.” When they entered a town, they did so as “a colony of heaven,” steadfast in the knowledge that they were there to obey God rather than man. King urgently longs for a day in which “the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear-drenched communities” and “the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation.”

If the eight clergymen to whom King addressed the “Letter from Birmingham Jail” were able to open their hearts and sincerely look at what was transpiring in their city from the protestors’ point of view, it seems likely that they would have admitted the justice of his cause. Like all great advocates, King was not merely attempting to defeat his opponents and win an argument. He was calling them to see the truth, one which would not embarrass or delegitimize them but open up possibilities for a better life for them, their community, and all of humankind.