Psychology

Why Horizontal Popularity Is Better Than Vertical Popularity

You want your fame to be horizontal, not vertical.

Posted May 21, 2018

About three years ago, I walked into the book section of a Hudson News in Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and found myself in a state of astonishment. There was an entire shelf filled with only one book. That is, hundreds of copies of one book. For months afterward I would go into bookstores in the airport just to count the copies of it, and still there would be rows upon rows. The book was Modern Romance by Aziz Ansari.

And do you know how many shelf spaces Hudson News dedicated to Modern Romance last time I was in the airport? None.

Here’s another book they generally fail to stock at Hudson: The Principles of Psychology by William James. The absence of Principles is, I suppose, less surprising than the absence of Modern Romance. It was published in 1890. Considered the founding text of psychology, Principles was the culmination of a decade of James’s work, throughout which he was consistently sidelined by battles with various illnesses. In it, James successfully forecasts pretty much everything we still care about in psychology more than a hundred years later. The table of contents reads like a syllabus for Psych 101: it covers sensation, attention, habit, memory, association, perception, the brain, imagination, reasoning, instinct, emotions, and free-will, to name a few. Not only does it cover the same topics, but what it says about them is still largely representative of how we think about them today. Of course, it doesn't cover the precise details of the experiments run over the last century. But it paints a picture of human behavior with the same broad strokes that we still use now. If you want to have a really deep understanding of psychology as a field, you could do worse than reading Principles. In fact, I’m not sure you could do a whole lot better.

It is not an overstatement to say that The Principles of Psychology is taught in every introductory psychology course. And not just the ones that have already been taught, either. James and his famous text will probably be taught in every single intro to psych that anyone will ever bother to teach. The number of people who have engaged with this text is huge. It is, in this sense, popular.

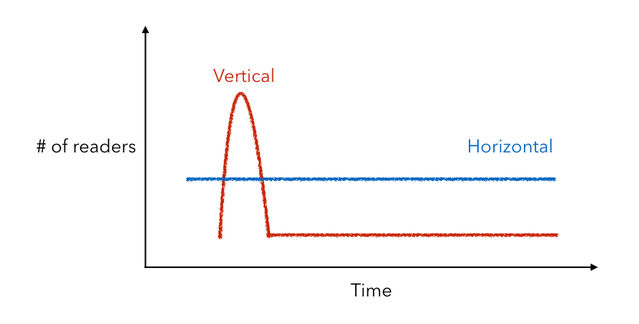

But the kind of popularity that it enjoys is completely different from the kind that a book like Modern Romance experiences. The reason we consider Modern Romance popular is because there was a certain point in time where practically everyone was talking about it. But soon after it appeared on the scene, the buzz dissipated. If you were to plot its popularity over time—with the number of people reading it on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis—then it would form a spike, almost like a vertical line. There would be a huge burst when it first came out, then it would drop off. It would look like this:

Modern Romance enjoyed vertical popularity. Its readership was confined to a relatively small section of time. But what if you made the same plot for James’s Principles? Sure, his book made a splash when it was published, even in 1890. It made him world-famous. But it wasn’t anything like the sales numbers for Ansari’s book. For Principles, popularity comes from a sustained readership over time, not all at once. Its plot would look like this:

This is characteristic of horizontal popularity. It’s horizontal because it accumulates its mass over time. It doesn't necessarily have a huge vertical spike. Even if there were one at the beginning, it wouldn’t be responsible for the majority of its popularity in the long run.

So what’s the difference between horizontal and vertical popularity? For one thing, horizontal popularity is actually the more difficult kind of popularity to achieve. Most books that are popular are vertically popular. Most likely, that includes any book that’s selling well on the shelves of Hudson News right now. Inclusion on the shelves of Hudson News is actually a pretty good proxy for vertical popularity. If you think about it, the primary demographic of airport bookstores are people who, knowing they are about to be sealed into a flying tube for several hours, think to themselves, “Gee, perhaps I should find something to do with that time.” The books you pick up there tend to arouse short-term interest rather than long-term devotion. Certainly, no one will be teaching them in a college course in a decade. In contrast, horizontally popular books are Freud's writings (also taught in every psychology introductory course), the Bible, Infinite Jest, Harry Potter, and the usual canon of literary works, to list a few that come to mind. They are, in a word, the classics—as worthwhile now as they were back when they came out.

That we consume a consistent diet of vertically popular works should, I think, give us pause. The defining feature of vertical popularity is that it is important now, but it isn’t going to be later. A good book, like a mutual fund, should be judged by its return on investment. You’re going to spend 10 hours reading it, let’s say. Do you want something that’s going to stick in your mind for a decade to come and keep paying dividends? Or do you want something that’s going to fizzle out and leave you with the suspicion that you shouldn’t be taking book recommendations from the same person who gives you financial advice? If you had read Principles a hundred ago, then you would have understood something substantial about psychology. The same is true about it today. And if, through all the changes in psychology over the past century, James’s work has remained relevant, I’d be willing to bet that the same will be true in another hundred years.

References

Ansari, A., Klinenberg, E. (2015). Modern romance. Penguin Press.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology.