Health

The Danger of Back to School

Children’s mental health crises plummet in summer and rise in the school year.

Posted August 7, 2014 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Imagine a job in which your work every day is micromanaged by your boss. You are told exactly what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. You are required to stay in your seat until your boss says you can move. Each piece of your work is evaluated and compared, every day, with the work done by your fellow employees. You are rarely trusted to make your own decisions. Research on employment shows that this is not only the most tedious employment situation, but also the most stressful. Micromanagement drives people crazy.

Kids are people, and they respond just as adults do to micromanagement, to severe restrictions on their freedom, and to constant, unsolicited evaluation. School, too often, is exactly like the kind of nightmare job that I just described; and, worse, it is a job that kids are not allowed to quit. No matter how much they might be suffering, they are forced to continue, unless they have enlightened parents who have the means, know-how, and will to get them out of it. Including homework, the hours are often more than those that their parents put into their full-time jobs, and freedom of movement for children at school is far less than that for their parents at work.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, many people became concerned about the ill effects of child labor on children’s development and wellbeing, and laws were passed to ban it. But now we have school, expanded to such a degree that is it equivalent to a full-time job—a psychologically stressful, sedentary full-time job, for which the child is not paid and does not gain the sense of independence and pride that can come from a real job.

Elsewhere (e.g. here) I have presented evidence that children, especially teenagers, are less happy in school than in any other setting where they regularly find themselves and that increased schooling, coupled with decreased freedom outside of school, correlates, over decades, with sharply increased rates of psychiatric disorders in young people, including major depression and anxiety disorders.

Now, in August, we are beginning to see the “back to school” ads, and I have been wondering about the relationship of children’s mental health to the school year. It occurred to me that an index of that relationship might be the numbers of psychiatric emergency room visits by school-age children that occur each month. Do they decrease in the summer, when (for most kids) school is not in session?

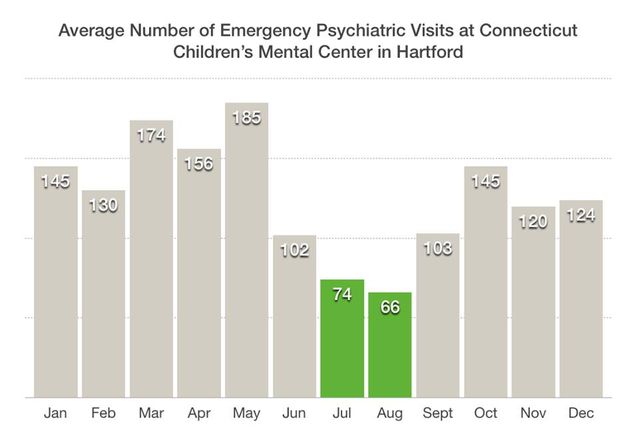

In a rather extensive search of the published literature, I found only one publicly available set of data on this—in an online article dealing with children’s emergency psychiatric visits at Connecticut Children’s Mental Center in Hartford (here). The primary point of the article was that such visits have risen dramatically in recent years and wait times in the ER have grown longer. However, an interactive graph in the article shows the number of such emergency visits for every month, for every year from 2000 through 2013. Even a quick glance at the graph made it obvious that, every year, the number of visits dropped in the summer and rose again in the school year.

In order to quantify this, I calculated the average number of visits, per calendar month, for three years—2011 through 2013. I included only those visits that were serious enough to lead to at least one overnight stay at the center (including all visits would have produced the same general finding). Here are the data:

Just as I predicted, July and August are the months with, by far, the fewest children’s psychiatric ER visits. In fact, the average number of visits for those two months combined (70 per month) is less than half of the average during the full school months (142 visits per month for the nine months excluding June, July and August). June, which has some school days (a number that varies depending on the number of snow days to be made up), is also low, but not as low as July and August. Interestingly, and not predicted by my hypothesis, September is also relatively low, equivalent to June. It seems plausible that September is a relatively relaxed warm-up month in school; serious tests, heavy assignments, and report cards are yet to come. It may take a few weeks back in school before the stress really kicks in.

Someone might argue that the seasonal variation in mental health crises reflects the weather, not the school year. However, that argument falls on its face when we look at the other months. The month with the highest rate of children’s mental health ER visits is May, and May is generally a beautiful month, weather-wise, in Connecticut, but it may well be the toughest month of school. May is the month of final tests, due dates for papers, and the crunch to make it through the rest of the curriculum.

These, admittedly, are data from just one children’s mental health center. I’d love to find more data to test the hypothesis. If you know of such data, or if you are motivated to do some research to dig such data out of a children’s mental health center in your community, let me know! Meanwhile, if you are a parent of a school-age child thinking about “back to school,” keep this in mind: The available evidence suggests quite strongly that school is bad for children’s mental health. Of course, it’s bad for their physical health, too; nature did not design children to be cooped up all day at a micromanaged, sedentary job.

---------

And now, what do you think about this? … This blog is, in part, a forum for discussion. Your questions, thoughts, stories, and opinions are treated respectfully by me and other readers, regardless of the degree to which we agree or disagree. Psychology Today no longer accepts comments on this site, but you can comment by going to my Facebook profile, where you will see a link to this post. If you don't see this post near the top of my timeline, just put the title of the post into the search option (click on the three-dot icon at the top of the timeline and then on the search icon that appears in the menu) and it will come up. By following me on Facebook you can comment on all of my posts and see others' comments. The discussion is often very interesting.

--------

Addendum

Another view of the data, provided by Scott Noelle:

Note added Aug. 15, 2022: For an update on relationship between children's mental health breakdowns and the school year, see here.