Anxiety

Panic Attacks: Discovering Panic’s Tricks

I use metaphors and examples to explain the nature of panic attacks.

Posted August 12, 2018

In my previous post I began talking about panic attacks, which are unpleasant experiences characterized by a sudden and strong rush of intense fear.

As I noted, the self-help solution to managing panic attacks is to lean into them instead of trying to fight them or to escape from them (i.e. the fight-or-flight response). This, of course, sounds counter-intuitive, and is the last thing a frightened person would ever consider doing.

So I am going to use some examples and metaphors to elucidate the nature of fear and panic, so that by the time I talk more about leaning into fear (which will be the subject of the next article in the series), the idea will not sound so frightening and absurd.

Fear is not all bad

Think of a wonderful summer day, nice and warm. A cool refreshing breeze is blowing. Your mind is completely relaxed, and your body is comfortably limp.

In this state, are you prepared to run away from a lion that has escaped from the zoo and has just spotted you?

Probably not.

The rush of fear and all the physiological events that our bodies experience when we are faced with a serious threat (e.g., the lion), have a survival purpose. The changes in blood pressure, muscle tension, etc, prepare our bodies to fight the threat or to run away from it...very fast.

In short, these physiological processes are useful and help us survive. So it is not a good idea to get rid of fear. It is better to try to reduce those fearful reactions that are so powerful that they are paralyzing; and to try to lessen fearful reactions to situations that do not pose an actual threat. This is more difficult than it may appear. Perhaps the following section can help explain why.

Fear as a radar

For the moment, think that your body is a well-protected country. Now imagine that your country’s only radar has detected a large wave of enemy bombers approaching your borders.

What will follow is the equivalent of some of the fight-or-flight physical events that occur during a panic attack (e.g., heart and breathing rates speed up, etc). This complex sequence of events is intended to prepare you for defense/offense: You sound the air-raid sirens, people rush into bomb shelters, roads are blocked, businesses shut down, soldiers are deployed, warplanes take off….

Assume, however, that no bombers come. Upon closer look, it turns out that the radar had malfunctioned and had mistaken a flock of crows flying over the borders for airplanes. Well, that is a relief. Things can return to normal. But what if just now the radar once again appears to detect an enemy plane? Are you going to ignore it, if an expert tells you that the radar likely malfunctioned? It is your country, after all, and you are responsible for its survival. Are you willing to accept the risks? And what if this repeats over and over again?

Similarly, during panic, we assume the presence of a threat when there is none. But our fear response is truly central to our existence, informing us and preparing us to face both internal and external threats (e.g., illness, wild animals); furthermore, it often feels much more certain and true, than the words of the healthcare professional sitting across from us. So we trust it more.

A panic attack informs us about a threat in a way that is frightening itself. So we fear not only the threat but also our own intense fear response. Our intense fear reaction intimates that our very survival is seriously threatened. No wonder why many people who experience panic attacks assume that they are going crazy or dying.

How panic works (Bill’s first panic attack)

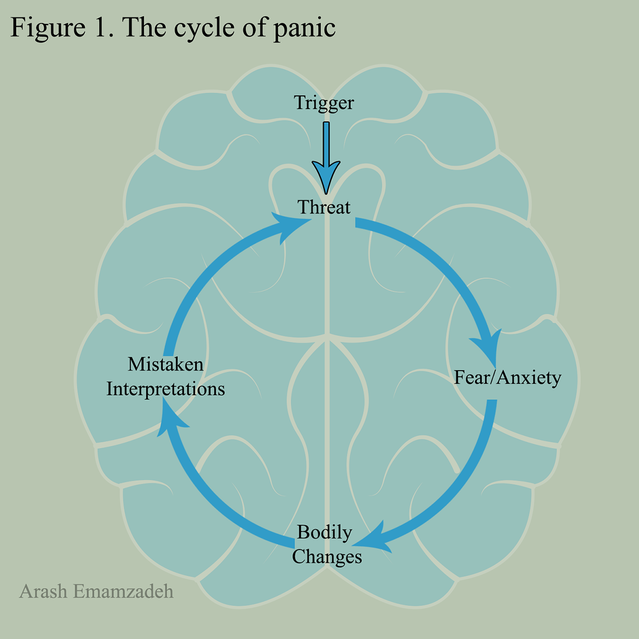

Generally speaking, a panic attack depends on both the occurrence of new or different physical sensations, and a fearful misinterpretation of what is happening, which then intensifies bodily sensations. This can create a vicious cycle, as I will describe below.

While a detailed examination of the mechanisms of panic is beyond the scope of this post, to give you an idea of how the panic cycle works, I will use an example concerning an anxious person named Bill who experiences a panic attack for the first time.

It is a hot and humid morning. Bill did not sleep well the night before. His body is tense. He decides to go out. He bends down to tie his shoes, but as stands up back up he feels a little dizzy. He also notices that his heart is beating a little fast. Bill wonders what is going on, and begins to feel anxious.

It is not clear what caused the sensations (like dizziness) that triggered Bill’s anxiety. They may have been related to his sleep troubles, the heat, etc, but the important thing is that Bill perceived them as a threat. It is at this point that the cycle of panic may begin (top of Figure 1). But will it?

Bill notices that his breathing rate has increased also. He looks in the mirror. There are a few beads of sweat on his forehead. He sits back down on the couch, vigilantly observing his body for more signs of something terrible.

Could he be having a stroke, like that young man in that medical documentary he watched last month? His breathing becomes faster and he feels more dizzy. Noticing these new changes, Bill starts to worry much more, thinking that he is losing control and that something terrible is imminent.

Notice how Bill’s fear and anxiety has resulted in changes such as faster breathing and feeling even more dizzy (look at the left side of Figure 1, starting from the bottom). Bill is misinterpreting these sensations as further evidence of a serious threat. Naturally, the assumption of a serious threat results in even more fear and anxiety. In short, Bill is trapped in a vicious cycle.

Things get worse very quickly. Bill’s forehead is pouring sweat, he feels nauseous, his hands are shaking, and by now he really believes he must be having a stroke or dying. He wants to call 911 but his legs are shaking so much he can’t get up. He begins praying....

And five minutes later, feeling exhausted, his face and shirt completely wet with sweat, Bill’s breathing is back to normal. The attack is over. He is still not sure what just occurred. But one thing is clear to him: He wants to make sure he will never ever experience anything like that again.

Unfortunately, however, the more we resist and fear our own panic response, the stronger it gets. Why? Because we do not allow ourselves to learn that despite this intense rush of fear, and despite our catastrophic interpretations, there is no imminent threat. We do not give ourselves the opportunity to habituate.

Instead, we are deceived by our own fear response. But if we were to pull back the curtain, we would see the complex experience of panic for what it really is: Simple and familiar fear. Now that, we know how to handle.

In my next post in the series, I will discuss the management of panic attacks. Rest assured, we are not going to let panic trick us so easily anymore.