Happiness

What Does It Take to Be Truly Happy?

New research shows people disagree with the scientific definition of happiness.

Posted February 13, 2017

Start by imagining a man named Tom:

Tom always enjoys his job as a janitor at a local community college. What he likes most about his job is how it gives him a chance to meet the young female students who are attending the community college. Almost every single day Tom feels good and generally experiences a lot of pleasant emotions. In fact, it is very rare that he would ever feel negative emotions like sadness or loneliness. When Tom thinks about his life, he always comes to the same conclusion: he feels highly satisfied with the way he lives.

The reason Tom feels this way is that every day he goes from locker to locker and steals belongings from the students and re-sells these belongings to buy himself alcohol. Each night as he's going to sleep, he thinks about the things he will steal the next day.

Now ask yourself about what Tom feels like: Does Tom feel bad? Does he feel satisfied with what he's doing? Does he feel good?

Okay, regardless of what you thought about those questions. Now just ask yourself this: Is Tom happy?

If you’re anything like the participants in our studies in a new paper in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, the answer to these two kinds of questions will come apart. People tend to agree that Tom feels good and is satisfied, but at the same time, they don't agree that he is happy. This seems to suggest that people think there’s more to being happy than just feeling good. Perhaps to truly be happy, you also have to be good.

What’s striking about this pattern of judgments is that it suggests ordinary people think about happiness in a way that contradicts the definition that is widely used by scientists. For scientists who research and measure happiness (or politicians who make policy decisions based on increasing happiness), being happy is nothing more than the combination of feeling good and being satisfied — it really doesn't matter why you feel that way.

To investigate why people’s judgments about happiness were being influenced by whether or not the person was living a morally bad life, we conducted a number of further studies.

The first thing we thought was that maybe participants were just misunderstanding the question. Perhaps trained academics wouldn’t show this same pattern of judgments, and would instead judge that immoral people were happy as long as they felt good. To test this, we asked a bunch of philosophers and psychologists to take our study. The results were striking. There was simply no difference in who they judged to be happy: philosophers and psychologists, just like everyone else, thought people who were living immoral lives were less happy.

Next, we wondered if maybe it was that, in general, people don’t want to attribute good things to bad people, and so everyone was simply reluctant to say that an immoral person was happy. To see if this was right, we tried to teach people about the emerging research that shows all of the ways in which happiness can actually be bad for you. (It’s true! Watch the video lecture we showed participants for yourself).

The thought was that if we told people about all of the ways in which happiness was bad, then perhaps they’d be more willing to say that bad people actually can be happy. To our surprise, though, we didn’t find this at all. Whether participants were taught about the ways that happiness was surprisingly bad (or surprisingly good) people’s responses were always the same. They continued to think that bad people couldn’t truly be happy.

We kept going and ended up doing a large number of further studies to investigate the impact of morality on judgments of happiness. In the end, what we ended up realizing was that this pattern actually wasn’t the result of a misunderstanding or bias at all. Rather, it seems that people straightforwardly understand that part of being happy is being good, and so if you aren’t good, you can’t truly be happy. If you’re curious, feel free to take a look at the full set of studies or participate in a video-demonstration of this kind of experiment.

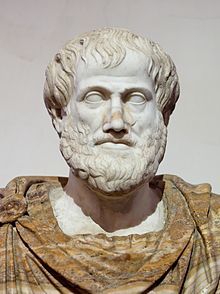

What’s intriguing about these findings is that while these studies were conducted on participants in the 21st century, the idea that they illustrate is extremely old. In fact, Aristotle long ago argued that one could not truly be happy if one were not virtuous. Perhaps there are still some things that contemporary psychologists can learn from ancient philosophy.

-This post was guest-written by Jonathan Phillips, who was the lead author on this research.

References

Phillips, J., De Freitas, J., Mott, C., Gruber, J. & Knobe, J. (2017) True happiness: The role of morality in the folk concept of happiness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(2), 165-181.