Self-Esteem

A Special Way for Self-Esteem to Transform Relationships

Empowering your relationships with a research proven virtuous cycle.

Posted January 29, 2018

Under good circumstances, having a healthy long-term romantic relationship means providing many things for one another, from tangible to intangible, overt to subtle. Ideally, individuals in a couple are not only intimate romantic partners but life partners, even coaches for bringing out the best in one another. Couples can truly strive to be a smoothly-oiled team, providing support, counsel and concrete assistance with personal pursuits and goals, professional development, weathering life’s challenges resiliently, parenting, building and maintaining family and social relations, and self-actualization.

When things aren’t going well, individuals in a couple can be detached and preoccupied with other pursuits, neglecting one another. Or one person may be motivated and active in being a good partner, while the other is more checked out, leading to an unbalanced relationship and resulting dysfunction and dissatisfaction. Couples can engage in unhealthy relationships, unwittingly repeating developmental patterns, re-traumatizing and traumatizing anew one another. Couples can actively undermine one another, causing direct harm to themselves and those around them, culminating in destructive and painful endings which never seem to reach closure.

What makes for a fine-tuned relationship?

There are many important factors in determining how couples function. Over the years, relationship researchers have focused in on a special cluster of interconnected traits, comprised of self-esteem, self-efficacy and esteem support. Each person has an opportunity to provide different types of support and encouragement to their partners. When they both provide this support in a mutually interlacing way, it becomes a unified and unifying process, synergistic.

How could couples achieve this (admittedly idealized) flow state? As reviewed by Jayamaha and Overall from the University of Auckland in their important work on couples self-evaluation in support, esteem and self-efficacy (2018), the study authors note that prior research has shown that higher self-esteem begets greater confidence in caregivers to provide care and that this kind of support, in turn, increases feelings of self-esteem in care recipients.

People with higher self-esteem are likely to see themselves as having globally greater self-efficacy, including greater confidence in their ability to support others effectively. Furthermore, they note that self-efficacy is one basis for motivation to deal with challenges. Without a sense of self-efficacy, people are more likely to feel helpless and pessimistic, giving up too soon. When people feel self-efficacy, a determinant of resilience, they try harder and keep trying in the face of challenges. They also are inclined to take better care of themselves when stressed, rather than letting routines fall by the wayside. Self-efficacy must not be confused with self-sufficiency, which is a useful trait but in extreme interferes with social relations and in particular can lead to help-rejecting behaviors.

Finally, the authors note that according to prior researchers, folks with high self-esteem on average experience higher levels of self-efficacy, perform better, and enjoy a healthy sense of pride in their accomplishments. People with greater support efficacy use a broader range of behaviors in efforts to help their partners, demonstrating greater cognitive flexibility in both supportive and problem-solving behaviors.

Why is esteem support so crucial?

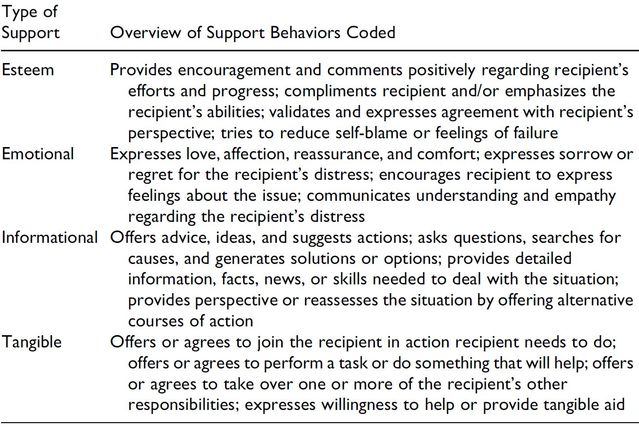

Jayamaha and Overall describe a very special form of support called “esteem support”, which focuses in on specific efforts to enhance others’ self-esteem. This has been shown to be a crucial factor in performance situations, such as for coaching professional athletes. More than support by providing information, pragmatic assistance and emotional support, targeting esteem support gives that extra boost which others need. In fact, they note that research has shown that in couples esteem support is unique among other varieties of support. When other forms of support are used more than one partner wants, it leads to marital problems—with the potential to become suffocating and even coercive.

However, researchers found that in the same couples, esteem support is associated with positive outcomes. The emotional impact of esteem support on recipients is largely rewarding and pleasant, deeply desired but often unspoken or communicated clumsily, but when present filling unmet needs for recognition, praise, and encouragement potentially free from the pressures of other forms of support. Many people don't even realize they need esteem support, but once they start to receive it they realize something may have been missing and can feel like finally coming home.

A deep-dive into couples mutual esteem building.

In order to better understand the effects of the three factors of esteem support, self-esteem and self-efficacy in romantic relationships, Jayamaha and Overall conducted two studies to bring out the details of what is happening, what works and what does not. In the first study, they set out to see whether higher provider self-esteem predicts greater levels of esteem support for recipients facing challenges. In the second study, they wanted to clarify the sequence of factors leading to synergistic and effective support, looking at the immediate impact on self-efficacy and esteem for recipients of provider caregiving efforts as well as the impact several months later.

For the first study, they analyzed data from a group of 61 young heterosexual couples, half living together, 15 percent married, 30 percent in a “serious” relationship, and 6 percent dating one another. Using accepted instruments, they assessed participants self-esteem, attachment style, relationship quality, and type of support provided.

They found that providers with better self-esteem, in particular, gave higher levels of esteem support to recipients. There were no significant correlations with provider self-esteem and emotional, informational or tangible support. This shows, for this sample, the unique utility of provider self-esteem in bolstering struggling partners’ self-esteem, establishing this finding to further investigate the nuanced relationship among self-esteem, esteem support, and recipient self-efficacy.

In the second study, researchers delved further into understanding how support providers’ sense of self-efficacy related to esteem support, and how esteem support, in turn, impacted support recipient self-efficacy. Working with 85 couples, 42 percent married, 37 percent living together, and 20 percent dating seriously, with a mean age of 33 years and relationship length of nearly 8 years, they asked each member of the couple to identify three major stressful issues they were experiencing. Then, picking the most severe problem, that person was designed as the support recipient and their partner as the support provider. They were randomly assigned roles if they were at equivalent stress levels.

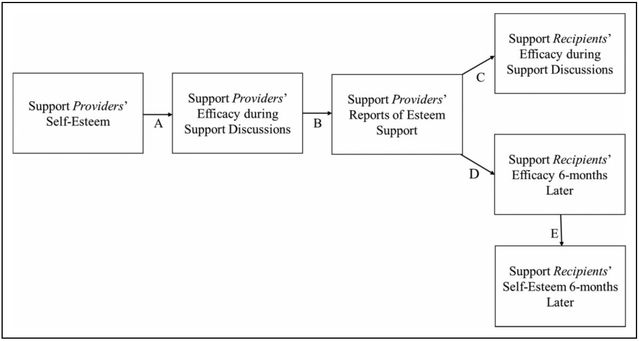

They were asked to talk through the issue they identified, and rated qualities of support, esteem, and efficacy immediately after speaking and upon a detailed review of the recorded conversation. Before the conversation, participants completed measures including depressive symptoms (which might interact with support and efficacy), and measures of self-efficacy for dealing with the stressor. Following the conversation, they completed measures of provider esteem support and practical support, recipients' perceptions of support, and both providers' and recipients' sense of how effective the support had been. To get a snapshot of how support dynamics play out over time, six months later those who responded (58 couples from the original group) re-rated where they were on similar dimensions. Researcher thereby tested aspects of this hypothetical model for self-esteem-related dynamics within couples:

Overall, they found that higher levels of provider self-esteem predicted the delivery of esteem support, which resulted in greater recipient sense of self-efficacy for dealing with the stressful situation. Variations in attachment anxiety, depressive symptoms, and demographic factors did not affect the statistical analysis. In addition, they found that recipients were attuned to esteem support, as levels of provider-reported esteem support were correlated with recipients’ experience of esteem support. At 6 months, they found lasting effects: provider self-esteem predicted higher reported self-efficacy, which in turn predicted higher esteem support and ultimately greater recipient self-esteem. Interestingly, while provider self-esteem predicted recipient self-esteem and self-efficacy, recipient self-efficacy was not found to be a mediator in between esteem support and recipient self-esteem at this later time. This could mean that recipients' self-efficacy had stabilized at a higher level over time, but further research would have to look into the ongoing effects more closely.

A virtuous cycle.

What does this mean for couples seeking to partner effectively? If we can increase the overall level of mutual esteem support, this very particular form of support, individuals in couples are likely to feel greater self-esteem and self-efficacy. These are interesting traits because they self-amplify. When we feel better about ourselves and believe we can do more, when we perceive ourselves from an imaginary external point of view, we actually enhance our behavioral capacities. We can intentionally provide esteem support by focusing on the what we know works here—making positive and encouraging comments about efforts to deal with stressful circumstances and highlighting progress our partners make, giving authentic and heartfelt praise for our partners’ capabilities to overcome issues, providing validation and agreement for our partners’ point of view, and helping our partners ease up on the self-blaming and fixate less on feelings of failure—allowing them to shift their attention to more optimistic and flexible approaches without being oppressive about it.

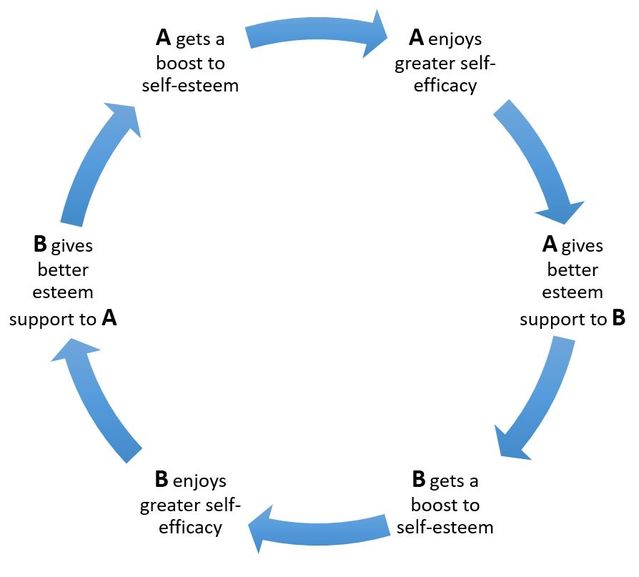

It’s easy to improve basic esteem support, but doing it well requires greater subtlety and practice. When our self-esteem is up, we are better at providing esteem support and we believe we will be able to do a better job at it, which helps to actually make us better at it. Especially when establishing new habits, it is helpful to adopt a planned and methodical approach, until the desired behaviors get baked-in and we shift over to maintaining them in good times and in bad. For two people, A and B, the virtuous cycle looks like this:

And when we provide esteem support to our partners, it raises up their sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem as well, which allows them, in turn, to provide esteem support more effectively for us when we need it. It is a virtuous cycle which is likely, when practiced over time, to positively alter the dynamics of the whole system as well as transform individual actors. Future research looking at ways to improve these key factors and tying them to actual relationship outcomes, while further elucidating the evolution of esteem support in romantic (and other interpersonal) situations, is needed to better understand how to develop interventions and best practices for learning to thrive together. As with sports, greater esteem support could help many different groups, from psychotherapists and patients to parents and children, in professional teamwork and for management.

While delivering esteem support is a key factor in (relationship) performance enhancement, esteem support is driven by and drives self-esteem and self-efficacy, which could be themselves turbo-charged by training, education, and practice. Don't be shy about providing esteem support—there's a good chance that not only will it pay off, but you'll get a great returns-on-investment. And when people around you offer esteem support to you, make sure you express appreciation and gratitude in recognition of what they are providing for you, encouraging them to keep doing it.

Special thanks to the study authors for assisting in the preparation of this article.

References

Jayamaha SD & Overall NC. (2018). The Dyadic Nature of Self-Evaluations:

Self-Esteem and Efficacy Shape and Are

Shaped by Support Processes in Relationships. Social Psychological and

Personality Science

1-13. Published online first https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617750734