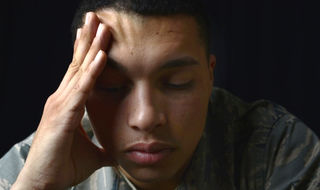

Trauma

Trauma and the Freeze Response: Good, Bad, or Both?

Have you ever been so paralyzed by fear that you simply dissociated from it all?

Posted July 8, 2015 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- A "freeze" stress response occurs when one can neither defeat the frightening, dangerous opponent nor run away.

- Phenomena such as phobias, panic attacks, and obsessive-compulsive behaviors can be viewed as freeze response symptoms.

- A person's original self-paralysis in reaction to trauma may repeat itself when triggered by a current circumstance.

Almost everyone is familiar with the fight or flight response—your reaction to a stimulus perceived as an imminent threat to your survival. However, less well-known is the fight-flight-freeze response, which adds a crucial dimension to how you’re likely to react when the situation confronting you overwhelms your coping capacities and leaves you paralyzed in fear.

Here, in brief, is how the survival-oriented acute stress response operates. Accurately or not, if you assess the immediately menacing force as something you potentially have the power to defeat, you go into fight mode. In such instances, the hormones released by your sympathetic nervous system—especially adrenaline—prime you to do battle and, hopefully, triumph over the hostile entity.

Conversely, if you view the antagonistic force as too powerful to overcome, your impulse is to outrun it (and the faster the better). And this, of course, is the flight response, also linked to the instantaneous ramping up of your emergency biochemical supplies—so that, ideally, you can escape from this adversarial power (whether it be human, animal, or some calamity of nature).

Where, in what you perceive as a dire threat, is the totally disabling freeze response? By default, this reaction refers to a situation in which you’ve concluded (in a matter of seconds—if not milliseconds) that you can neither defeat the frighteningly dangerous opponent confronting you nor safely bolt from it. And ironically, this self-paralyzing response can, in the moment, be just as adaptive as either valiantly fighting the enemy or, more cautiously, fleeing from it.

Consider situations in which, realistically, there’s no way you can defend yourself. You have neither the hormone-assisted strength to respond aggressively to the inimical force nor the anxiety-driven speed to free yourself from it. You feel utterly helpless: Neither fight nor flight is viable, and there’s no one on the scene to rescue you.

Say, you’re attacked by a ferocious dog who’s sunk his teeth into your neck and you’re totally at his mercy. In such an alarming instance, you’d experience trepidation, panic, horror, dread. And these extreme feelings would be so fraught with anxiety, so laden with terror, that almost no one is “gifted” with the resources required to stay fully in the present—which is precisely what’s needed to “process” emotional and physical completion, or release, of what so frighteningly besieges you.

Under such unnerving circumstances, “freezing up” or “numbing out”—dissociating from the here and now—is about the only and (in various instances) the best thing you can do. Being physically, mentally, and emotionally immobilized by your consternation permits you not to feel the harrowing enormity of what’s happening to you, which in your hyperaroused state might threaten your very sanity. In such instances, some of the chemicals you thereby secrete (i.e., endorphins) function as an analgesic, so the pain of injury (to your body or psyche) is experienced with far less intensity.

Additionally, if you’re not putting up a fight, the person or animal aggressing against you just might lose interest in continuing their attack. But whatever the provocation, if you can’t make the assailant disappear, you’re much better off “disappearing” yourself, by blocking out what’s much too scary to take in. So, in its own way, the freeze response to trauma is—if only at the time—as adaptive as the fight-flight response.

For a small child, the developmental capacity to protect is markedly limited. So, rationally or not, he or she would likely experience a whole host of situations as threatening to survival. Merely a look of rejection or scorn in the eyes of a disapproving parent, for instance, can make him or her feel uncared for, unloved, and abandoned, compelling the feeling of numbing out. And this is why the freeze response occurs far more commonly in children than in adults.

Such “paralyzing” psychological phenomena as phobias, panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and various anxiety states can frequently be understood as symptoms of a freeze response that never had the chance to “let go” or “thaw out” once the original experience was over. And many features of post-traumatic stress disorder directly relate to this kind of unrectified trauma.

Though it’s almost always entirely unconscious, some circumstance in the here and now can remind you of a trauma suffered years (sometimes, many, many years) ago. Never fully “discharged,” the original fear or panic linked to that memory compels you to react to the current-day trigger as though what happened in the past is happening all over again. And so your original reaction of self-paralysis can’t help but repeat itself. Your mind goes completely blank, your rational faculties missing in action.

What was adaptive as a child, dissociating from an event vastly beyond your capacity to handle, can become frustratingly maladaptive as an adult. Paradoxically, at its extreme, a reaction of dissociation could be not at all life-preserving but, in fact, life-threatening. For when you’re stymied by inappropriate, exaggerated fear, you’re in no position to act sensibly to whatever might be menacing you.

It’s been postulated that dissociating in the midst of a traumatic experience is the foremost predictor for developing PTSD symptoms later on (see, e.g., van der Kolk & van der Hart, 1989). And, as already pointed out, young children are particularly disposed to dissociate during episodes of trauma. So, for instance, a child who “froze” during incidents of frightening family abuse is, as an adult, especially susceptible to experience the freezing reaction again. And sometimes the current stimulus for such retraumatization isn’t anything specific. It may simply emanate from being in a state of highly exacerbated stress, which itself serves as an unconscious reminder of the acute stress linked to the initial trauma.

So if any of the above descriptions describe you (or someone you care about), I can hardly overemphasize how useful it might be to seek professional help. That way you can finally "put to rest" what, at the time of its first occurrence, you weren’t able to. By combining psychology with basic principles of biophysics, what a large variety of trauma resolution methods make possible (e.g., Sensorimotor Processing, Somatic Experiencing, etc.) is the opportunity to release the residual tension (or internal energy) that was left unresolved even after the actual trauma was over.

Finally, many chronic, stress-related diseases are now postulated by trauma experts as representing somatic manifestations of past unrectified trauma. It may, therefore, be invaluable to find a qualified practitioner to assist you in locating just where in your body this frozen energy still resides. And then help you—at long last—to discharge it.

References

R. C. Scaer, The Body Bears the Burden: Trauma, Dissociation, and Disease, 2001