Education

Do the Best Professors Get the Worst Ratings?

Do students give low ratings to teachers who instill deep learning?

Posted May 31, 2013

My livelihood depends on what my students say about me in course evaluations. Good ratings increase my chances for raises and tenure. By contrast, there is no mechanism in place whatsoever to evaluate how much my students learn--other than student evaluations (and, here at Williams, peer evaluations). So is it safe to assume that good evaluations go hand in hand with good teaching?

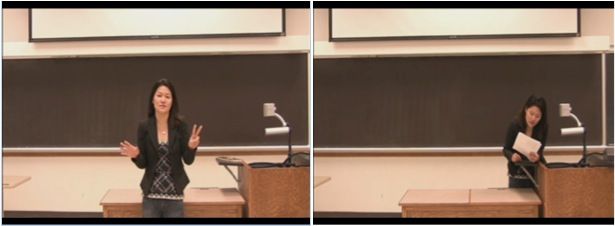

Shana Carpenter, Miko Wilford, Nate Kornell (me!), and Kellie M. Mullaney recently published a paper that examined this question. Participants in the study watched a short (one minute) video of a speaker explaining the genetics of calico cats. There were two versions of the video.

- In the fluent speaker video, the speaker stood upright, maintained eye contact with the camera, and spoke fluidly without notes.

- In the disfluent speaker video, the speaker stood behind the desk and leaned forward to read the information from notes. She did not maintain eye contact and she read haltingly.

The participants rated the fluent lecturer as more effective. They also believed they had learned more from the fluent lecturer. But when it came time to take the test, the two groups did equally well.

As the study's authors put it, 'Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Instructor Fluency Increases Perceptions of Learning Without Increasing Actual Learning." Or, as Inside Higher Ed put it, when it comes to lectures, Charisma Doesn't Count, at least not for learning. Perhaps these findings help explain why people love TED talks.

What about real classrooms?

The study used a laboratory task and a one-minute video (although there is evidence that a minute is all it takes for students to form the impressions of instructors that will end up in evaluations). Is there something more realistic?

A study of Air Force Academy cadets, by Scott E. Carrell and James E. West (2010), answered this question (hat tip to Doug Holton for pointing this study out). They took advantage of an ideal set of methodological conditions:

- Students were randomly assigned to professors. This eliminated potential data-analysis headaches like the possibility that the good students would all enroll with the best professors.

- The professors for a given course all used the same syllabus and, crucially, final exam. This created a consistent measure of learning outcomes. (And profs didn't grade their own final exams, so friendly grading can't explain the findings.)

- The students all took mandatory follow-up classes, which again had standardized exams. These courses made it possible to examine the effect of Professor Jones's intro calculus course on his students' performance in future classes! This is an amazing way to measure deep learning.

- There needs to be a lot of data, and there were over 10,000 students in the study in all.

The authors measured value-added scores for each of the professors who taught introductory calculus.

The results

When you measure performance in the courses the professors taught (i.e., how intro students did in intro), the less experienced and less qualified professors produced the best performance. They also got the highest student evaluation scores. But more experienced and qualified professors' students did best in follow-on courses (i.e., their intro students did best in advanced classes).

The authors speculate that the more experienced professors tend to "broaden the curriculum and produce students with a deeper understanding of the material." (p. 430) That is, because they don't teach directly to the test, they do worse in the short run but better in the long run.

To summarize the findings: because they didn't teach to the test, the professors who instilled the deepest learning in their students came out looking the worst in terms of student evaluations and initial exam performance. To me, these results were staggering, and I don't say that lightly.

Bottom line? Student evaluations are of questionable value.

Teachers spend a lot of effort and time on making sure their lectures are polished and clear. That's probably a good thing, if it inspires students to pay attention, come to class, and stay motivated. But it's also important to keep the goal--learning--in sight. In fact, some argue that students need to fail a lot more if they want to learn.

I had a teacher in college whose lectures were so incredibly clear that it made me think physics was the easiest thing in the world. Until I went home and tried to do the problem set. He was truly amazing, but sometimes I think he was TOO good. I didn't struggle to understand his lectures--but maybe I should have.