Eating Disorders

Shape Checking in Eating Disorders

What is it and how to address it.

Posted September 2, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

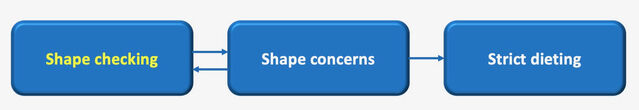

It is very common for people to check the shape of their bodies to some extent, but many people with eating disorders repeatedly do so, often in an unusual way. Such checking can become so ‘second nature’ that they may not be fully aware that they are doing it; for example, they automatically compare themselves with other people they see while walking down the street. Since body checking tends to be particularly influential in maintaining dissatisfaction with shape and encouraging dieting in patients with eating disorders (see Figure 1), it should be accurately assessed and eventually addressed.

Common examples of body checking include:

- Scrutinizing particular body parts in the mirror (or reflective surfaces).

- Measuring bodies using a tape measure.

- Pinching or touching body parts, assessing the tightness of particular items of clothing (e.g., trouser waistbands) and accessories (e.g., watches or rings).

- Looking down at their thighs or stomach—for example, when sitting.

- Comparing themselves with others (including the media images).

Body checking maintains eating disorders' three main mechanisms:

- It maintains concern about the shape of the body because the parts of the body that one does not like are continuously scrutinized.

- It makes even the most attractive people find ‘flaws’, as what we see depends largely on how we view ourselves.

- It amplifies apparent defects because persons with eating disorders tend to focus on what they don’t like, rather than looking at the bigger picture. As a consequence, they have no reference points for size or scale.

Strategies to address shape checking

Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E), a recommended treatment for all forms of eating disorders in adults and adolescents, addresses shape checking within the “Body Image” module adopting the following strategies and procedures.

First, patients are informed that shape checking needs to be addressed directly because it maintains body dissatisfaction, and consequently encourages dietary restraint and the adoption of other extreme weight-control behaviors. Patients are also informed that they may experience a short-lived increase in concerns about shape that it is usually followed by a marked reduction in these concerns, although some patients may need to engage in alternative forms of behaviors for a while.

Then, patients are asked to assess the shape checking in real-time in detail for two 24-hour periods, discussing the types of behavior that should be recorded.

Next, the therapist evaluates with the patients the reasons for and consequences of body checking, and discusses the forms of shape checking to stop and those to modify in nature and frequency.

The most common forms of shape checking to stop are:

- Unusual, non-normative, forms of behavior (e.g., pinching parts of the body to assess ‘fatness’; repeatedly touching the abdomen, thighs, and arms; feeling bones; checking the tightness of rings and watch-straps; looking down when sitting to assess the extent to which one’s abdomen bulges out over the waistband of one’s pants or the degree to which one’s thighs spread).

- Those that are usually secretive, as they would be embarrassing if someone else found out (e.g., using a tape measure to check thigh circumference; checking there is a gap between the thighs when standing with the knees placed together; and, when lying down, placing a ruler across the hip bones to check that the surface of the abdomen does not touch it).

Often patients succeed in stopping non-normative forms of shape checking without too much difficulty. In my clinical experience, it is best that they go ‘cold turkey’ rather than try to phase these behaviors out. Such behavior tends to undermine self-respect and, after a few weeks, stopping it is experienced as a relief.

The two main forms of shape checking that should be modified are:

- Mirror use.

- Comparison checking.

To address mirror use patients are asked first to assess frequency of mirror use; how long they spend looking in the mirror on each occasion; what exactly they are checking; which part they are looking at and which they are ignoring or avoiding; and what exactly they are trying to find out.

Then they are helped to use the mirror in a functional way, discussing: (i) when it is appropriate to use the mirror (e.g., to check hair and clothing, to apply or remove make-up, and/or shave); (ii) what forms of mirror use are inappropriate or unhelpful (e.g., focusing on body parts that one dislikes, and scrutinizing them for long periods); (iii) how to avoid magnifying apparent defects (e.g. avoid focusing on body parts that we dislike, and instead look at the whole body, including more neutral areas such as hands, feet, knees, hair), and take in the background environment to give a sense of scale).

Usually, there are two forms of comparison making that need to be addressed: (i) comparison with other people, and (ii) comparison with media images. The nature of these comparisons typically results in patients concluding that their body is unattractive relative to that of others. The comparison is often biased in one, or both, of two ways:

- Subject bias. The comparison is with someone attractive (selective attention). When making these comparisons, patients tend to choose biased reference groups composed of thin, good-looking people of the same gender and age. They fail to notice others who are less thin and good-looking. Thus, there is an inherent unfavorable bias both in the way that shape is assessed and in the objects of comparison.

- Assessment bias. The way the other person’s body is evaluated is cursory. In marked contrast to their prolonged negative appraisal of their bodies, patients’ assessment of other people is often based on uncritical snap judgments.

Patients are helped to assess and address these two biases and comparison making, and change the nature of the comparison. They are also encouraged to reflect on the notion of ‘attractiveness’, which is not only related to thinness, and to broaden their comparison making to include aspects of people other their shape (e.g., their hair, shoes, sense of humor, etc.).

As it is common for patients with an eating disorder to compare themselves with people portrayed in the media, it is important to ask the patients to monitor this form of comparison making, which might include images from magazines and/or the internet. To inoculate patients against the uncritical acceptance of media images, they should be educated (with examples) on the manipulation of images (airbrushing) and encouraged to do some research on the subject.

References

Dalle Grave, R., & Calugi, S. (2020). Cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

Calugi, S., El Ghoch, M., & Dalle Grave, R. (2017). Body checking behaviors in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(4), 437-441. doi:10.1002/eat.22677