Relationships

Taking Chances on Others: The Bumpy Road of Acquaintanceship

Exploring the different trajectories that our relations with others can take.

Posted December 16, 2020 Reviewed by Devon Frye

For obvious reasons, I have not met anyone new in a while. But I anticipate doing so in the future, and I wanted to talk a bit about what that’s like.

Those who have read any of my work know that I am a personality psychologist who specializes in how we make judgments of others, and the title of this blog highlights the fact that I don’t have supreme confidence in our general ability to understand others—especially quickly. Empirical work supports the notion that early impressions of personality are fraught with peril (See Table 5 of Connelly & Ones, 2010), and I have devoted a fair amount of my time to examining the process of getting acquainted in the hopes of helping people to remedy this issue.

But why this topic and not the myriad other possible topics of study available to a research psychologist? It’s fairly simple, actually: people don’t like me. OK, that’s not entirely fair. Several people like me quite a bit—maybe even love me—but what I mean to say is that I don’t make strong initial impressions.

More than one of my very good friends has informed me that they believed I did not like them in the early stages of our acquaintance. I have heard anecdotes wherein third parties tell my friends or colleagues things like: “You know, that Beer guy isn’t as dumb/mean/scary as I thought!” And while I’m pleased to have changed the minds of these individuals, I’m obviously troubled by the fact that I had to do so.

So, I was somewhat troubled when I came across this recent social media post, which was fairly popularly endorsed:

Obviously, this statement is taken out of context and may be very true in many circumstances, but if it’s a general rule, I’m in trouble. It took a lot of convincing to get my wife on board, and I simply don’t have the energy to constantly be pulling come-from-behind personal victories.

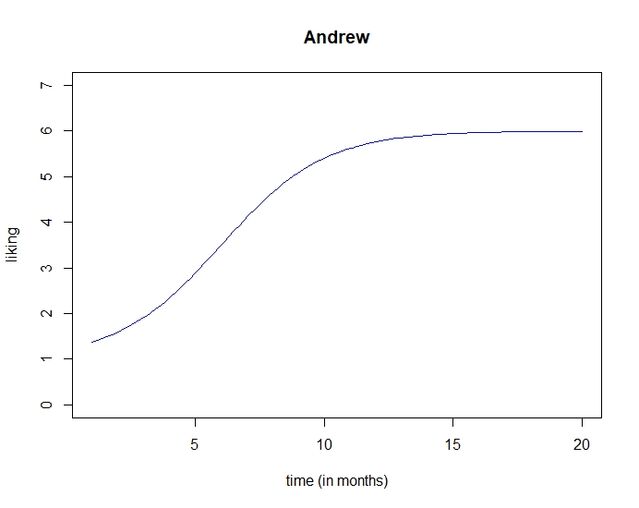

This got me thinking a bit about the various paths that liking in any relationship can take. For example, I’ve described something that looks like this as the way in which I make impressions on others:

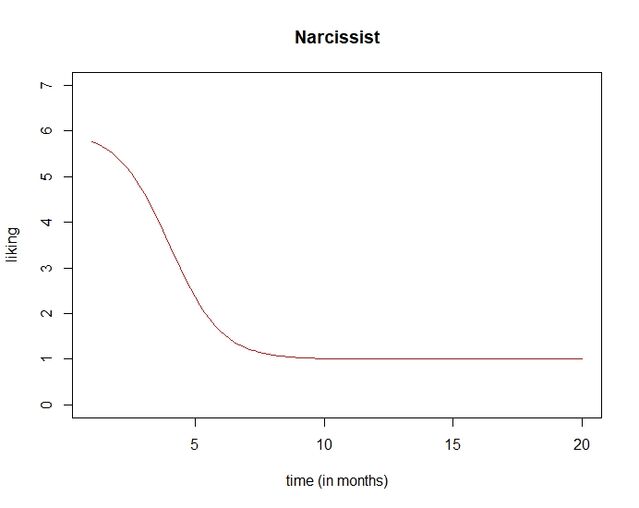

Now, is this variable across perceivers? Sure. Some people like me at first—it has happened. There might even be some who liked me better before they got to know me. And while we’d all prefer to just have a straight line at the top of the figure representing the manner in which others in our social world receive us, the truth is that there’s probably a lot of variability both across and within people and relationships. For example, your classic narcissist liking profile over time might look like this:

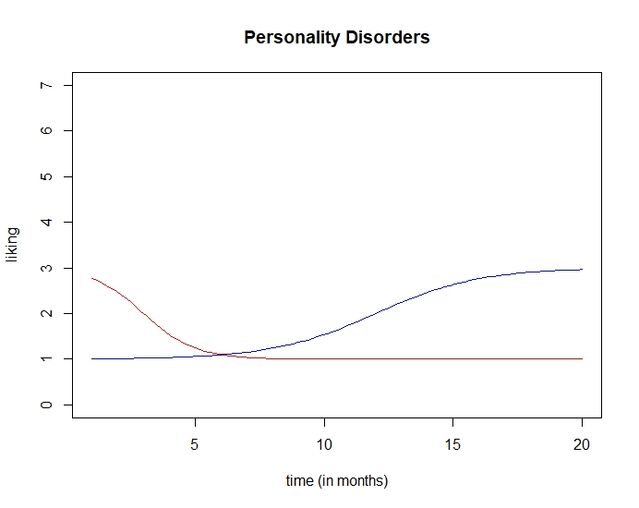

We know that narcissists tend to be popular early (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2010) but rub others the wrong way over time (Carlson, Vazire, & Oltmanns, 2011). Truly maladaptive personalities may find themselves unable to become widely liked or may even start behind and decline from there:

To my knowledge, there is very little available data that speaks directly to changes in liking over time in new relationships. This is largely because these kinds of studies are difficult to execute—the aspiring researcher must find a large population of people who do not already know each other and then come to know each other over a pretty significant period of time. Thus, longitudinal studies of romantic partners or existing friendship dyads (easier samples to obtain) won’t do. I wonder if, across relationships, people form unique aggregate profiles like those presented here, or if maybe each relationship follows its own unique path. I wonder if our ideas about people liking us track the trajectories of their actual liking, as is evidenced in metaperceptions of personality (Carlson, 2016).

Because I wonder these things, I built a little interactive app that you can use to determine your own generalized liking curve simply by answering four questions. Try it as many times as you like. Imagine it for different relationships that you’ve had. Plot your own liking of someone else you’ve known. Or just draw fun shapes. This is my gift to you, reader. Feel free to report back with your findings and suggest alterations (it is, admittedly, a modest attempt at capturing the idea).

In the end, someone might ask me why I care so much about liking when my primary focus is on knowing others (as opposed to liking). And my answer would be because these things are generally related (for a more nuanced discussion, see Wessels et al., 2020). If you initially don’t like someone, you often opt not to know them.

And sometimes, this is for a very good reason. A popular story around my household involves the time my maternal grandfather refused to allow my mother to date a young man based on an initial impression the night of the prospective date (ah, 60s patriarchy!). Years later, my grandfather sent my mother a newspaper clipping (ah, pre-internet communication!) detailing the man’s conviction for the murder of his erstwhile romantic partner. Score one for life-saving rapid impressions!

Some people are bad, it’s true. But most aren’t, I think. And in most cases, I don’t think taking the chance to learn more about people is particularly dangerous. Shortly after I came across the aforementioned tweet that (justifiably) cautioned against second chances, I came across this one:

Yes, this one, too, requires context for interpreting the author’s intentions—it seems a clear poke at their own naivete—but for someone like me, it was a Lloyd Christmas-ian oasis: you’re saying there’s a chance for me.

References

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2010). Why are narcissists so charming at first sight? Decoding the narcissism–popularity link at zero acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 132–145.

Carlson, E. N., Vazire, S., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2011). You probably think this paper’s about you: Narcissists’ perceptions of their personality and reputation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 185–201.

Carlson, E. N. (2016). Meta-accuracy and relationship quality: Weighing the costs and benefits of knowing what people really think about you. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 250–264.

Connelly, B. S., & Ones, D. S. (2010). An other perspective on personality: Meta-analytic integration of observers’ accuracy and predictive validity. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 1092–1122.

Wessels, N. M., Zimmermann, J., Biesanz, J. C., & Leising, D. (2020). Differential associations of knowing and liking with accuracy and positivity bias in person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118, 149–171.