Trauma

Rewiring the Brain After Injury—What a Simple Drawing Says

Fguring out how people process information.

Posted September 29, 2020 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Formal education trains people to be efficient, learning routines so that the tasks become hardwired. For example, once people learn to read, they automatically attempt to read when faced with text. The message may be indecipherable if written in an unfamiliar language, but in most cases, words are identifiable and are not mistaken for decorative patterns or meaningless scratches. Most people are not aware of their own cognitive processes.

But after a traumatic brain injury, people need to be made aware of the implicit rules that guide thinking processes, such as comparing and contrasting alternatives, defining problems, generating alternatives, and trial and error behavior.

In a previous Psychology Today blog on repairing and rewiring the brain, I gave the broad strokes of how mediated learning works. In this post, I would like to explain more of the process we mediators use to work with traumatic brain injury patients.

Whether we are aware of it or not, we all have a voice or voices inside our head that help monitor behavior and how we interact with the world. Often this is the first thing brain injury patients lose, because it is at such a high level of thinking. If any so-called metacognitive dialog remains, most often it is negative—Why can't I do this? What's wrong with me? Since mediators like myself usually don’t know how patients processed information pre-injury, we need to take cues from family members and people in similar professions to surmise a pre-state.

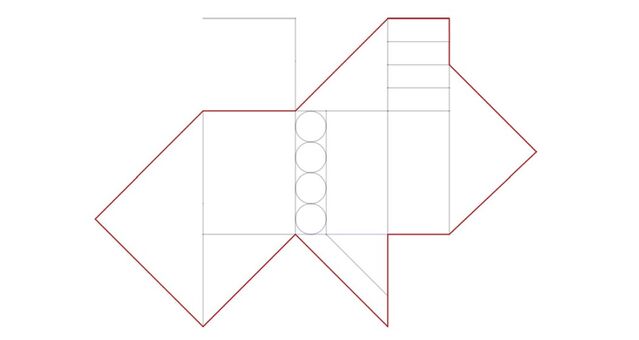

The neurocognitive influence of education is strongly evident in how people draw a complex figure, such as the one in Figure 1. As mediators, we can glean a lot of information about how the individual is approaching and interpreting visual information by how they approach copying this complex figure.

Participants are given different colored pencils in a prescribed order: red, green, blue, brown, black, yellow, purple, and pink. We then ask the participant to copy the figure, switching colors every 20 seconds. We can compare how post-traumatic head injury patients approach this figure with what we know about how it is approached by people from similar professions who do not have post-traumatic head injuries. Although not everyone within a given profession draws exactly the same way, definite patterns can be ascribed to particular groups.

For example, architects, engineers, and physicists tend to first focus their attention on the central image (shown as the red rectangle in Figure 2).

Entrepreneurs view the complex figure in an entirely different way. Business people tend to be “big picture” people, who concentrate on the broad outline rather than smaller details. This behavior shows up in the drawings as illustrated in Figure 3. Unlike the engineers, the entrepreneurs tend to focus on the outer areas of the drawing.

Accountants and others whose work requires a high level of organization are classic linear thinkers. If they usually read from left to right, they begin their drawings on the left and work systematically through to the right as in Figure 4.

Graphic artists, web designers, and other visually creative people are apt to start their drawings anywhere they see a strong pattern, such as the angles and the circles in Figure 5.

More than just a curiosity, how people draw the complex figure reflects how they envision information—whether they focus on the parts or the whole, whether they think problems through logically or span boundaries with analogies. The more successful people have become within a given field, the more likely they are to become mentally rigid. Their brains become structured to see problems in one way.

By focusing on the difference between how a patient dealt with the world cognitively before injury and how they deal with it post-injury, mediators can help bridge the gap, working with them to repair and rewire their cognitive processes so that they can again feel like they are functioning at what they consider to be an acceptable level.

How individuals approach this drawing gives us critical data about how to approach helping individuals repair and rewire their brains. In future posts, I will show what mediators do with the information gleaned from exercises like the one above, and how we decide what processes need to be addressed first and why.