Bias

Racism in Academic Publishing

Observations about race and peer review from a Black female professor.

Posted July 14, 2020

Structural Racism Behind the Scenes

With the current focus on anti-Black racism, there has been a fresh look at all of our cherished institutions and how structural racism may be at work behind the scenes. There are biases operating in academic publishing, even within the process of generating peer-reviewed scientific articles. These published works form the foundation of what we know (and think we know) in science but are not as solid as we’d like to believe.

I have become well-acquainted with the academic publishing process, having published way too many peer-reviewed articles and book chapters. I currently serve as an associate editor for several psychology journals, I am on the editorial board of several more, and I have even served as guest editor for a few special issues. I have peer-reviewed enough academic papers to put me in the 99th percentile on Publons, for those of you know that is. Yes, this means that I am officially a psychology nerd and probably need to get out more, but before I become derailed into a discussion about how hard you have to work to be Black and female in the academy (see Buchanan, 2020) I want to share some of my observations about race in publishing as a person in the thick of it.

Racial Biases in the Peer-Review and Publishing Process

In a recent article published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, Roberts and colleagues took a look at racial inclusion in top-tier cognitive, developmental, and social psychology journals. They concluded that “systemic inequality exists within psychological research,” noting that few journals focused on the issue of race, most journals had White editors, and empirical papers included fewer participants of color when written by White authors.

This was not news to me, as my success as a research psychologist hinges on my ability to keep churning out high-quality, publishable, scientific material—an endeavor made doubly difficult because most of my scholarship is about race, racism, and mental health inequities. I have found that these are not favored topics by editors and reviewers, and it can be easier for them to desk reject an article than do the work of identifying qualified people for peer review.

Interestingly, no journals published by the Association for Psychological Science (publisher of Perspectives on Psychological Science and several other top journals) were included in the aforementioned analysis. This struck me as interesting, as my sense had been that APS was not always a very welcoming place for scholars like myself. This does seem to have shifted recently, so much so that I am now an APS member and guest-editing a special issue on microaggressions, but this has not always been the case.

An Emory professor took it upon himself to discredit the entire concept of microaggressions and related scholarship, under the notion that the concept was too fuzzy and science was too thin. He also seemed to imply that people of color who complain about microaggressions were probably just neurotic. Because of his very senior position in APS and the field of psychology overall, his unscientific paper got published into this very same journal (Perspectives), causing incalculable damage to this growing area of study. Media headlines said things like “University Professor says ‘microaggressions’ don’t exist.” Some graduate programs stopped offering diversity courses altogether. As a scholar of racism, I knew the article was very wrong. I dusted off a dataset that I thought might be able to address one of his key assertions and fired up SPSS. I wrote up the results and submitted the article to an APS journal where he was the editor. I said, “Good news, now we have data to look more closely at the ideas advanced in the paper you wrote.” But although he welcomed the submission, he rejected the paper.

Even so, on the lecture circuit, I took every opportunity to debunk his erroneous claims about microaggressions research. Many colleagues kept telling me I needed to publish a rebuttal, but I was not keen on writing yet another paper that would be hard if not impossible to publish. And it seemed pointless to publish the rebuttal anywhere other than the journal in which the original article appeared—a journal that seemed hopelessly out of reach for someone like myself. But after much encouragement by senior White allies, I took a stab at it. This required jumping through proverbial flaming hoops in the submission and review process (read: racial bias in publishing), but thanks to an incredible amount of work combined with wonderful colleagues, and a supportive new editor, my paper was finally accepted. It took a village and over a year for it to finally go to print, and much to my chagrin the journal solicited a rebuttal from the author of the original paper, which was (accidentally) published before my paper was released—the ultimate microaggression during an academic debate about microaggressions. Despite putting more blood, sweat, and tears into this paper than anything I have ever written I was still subject to the first rule of Western society, I mean, chess—White always goes first. (And of course, that's not racist at all.)

Desk Rejection Common

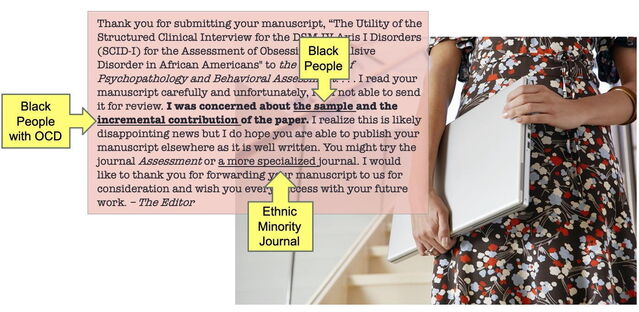

In my own experience as a Black female scholar, publishing papers about Black people means getting repeated desk rejections. Yes, I know everyone who does this work gets rejections all the time. But after having written as many papers as I have, and after having peer-reviewed just as many, and having handled scores of paper in an editorial role, I do know some things. I know when a paper is making a relatively small contribution to science (and thereby deserving of a mediocre outlet) versus something that is really exciting and important (thereby deserving a higher caliber outlet). And I also know from experience that papers about Black people will take me about five times longer to find a home than an identical paper with a mostly white sample. And there are journals that will never ever publish my papers no matter how good they are.

After desk rejection, editors will often suggest that I resubmit my work to a “specialty journal” (read: ethnic minority journal). And journals with names that suggest openness to papers about race may still be treacherous terrain. A prime example of this is my many failed attempts at getting a paper into the Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. Despite submitting articles that are well-within the journal’s stated scope (including one that almost made it into the American Psychologist), my work is not welcome. I have had desk rejections for papers on racism at universities, development of a novel anti-racism student workshop, a new measure of microaggressiveness in college students, and the voices of microaggressions experienced by Black students. One of my articles was rejected by a White editor after the revise-and-resubmit process but before being sent back out for re-review (despite us being completely responsive to reviewer feedback) because the editor couldn’t figure out why there was a need to develop a measure of White allyship at all.

Most recently, BMC Psychology initially rejected an article I wrote about racism experienced by Black people at white universities, despite a spread about Black Lives Matter on the BMC homepage. The paper was not rejected because there was any identified problem with it, but because they said they could not find reviewers. Keep in mind, this is at a time where anti-Black racism is leading every news story and there is interest in American race issues around the world. An article like this should have been fast-tracked through due to the timeliness of the content, much like COVID-19 articles are being prioritized now. But instead it was rejected without review. When I tweeted about my dismay over this, I discovered at least one of my suggested reviewers was not even approached. Apparently, BMC’s proclamations about Black lives mattering did not make it down to the actual gatekeepers of journal content, the editors and assistant editors. (BMC has since agreed to look for more reviewers but has not yet told me what anti-racism efforts they have actually implemented.)

Even worse is that some journals have a hidden White-supremacist agenda. This means that papers asserting white people are superior to people of color are quietly spirited through a sham review process before appearing in print (here is one example of this). This should not be too surprising given that nearly the whole field of psychology is rooted in racism, with many measures developed for the purpose of trying to scientifically prove White racial superiority (Guthrie, 1976). But I explain this more sinister facet of racism in academic publishing in my next article in this series.

Next: Psychology’s Hidden History: Racist Roots and Poison Fruits

References

Buchanan, N. T. (2020). Researching while Black (and female). Women & Therapy, 43(1-2), 91-111.

Williams, M. T. (2020). Microaggressions: Clarification, evidence, and impact. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 3-26. doi: 10.1177/1745691619827499

Williams, M. T. (2020). Psychology cannot afford to ignore the many harms caused by microaggressions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 38-43. doi: 10.1177/1745691619893362

Guthrie, R. (1976) Even the rat was white: a historical view of psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial Inequality in Psychological Research: Trends of the Past and Recommendations for the Future. Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620927709