Ethics and Morality

The Psychology of (In)Equality and Fairness

Feelings about the fairness of equal portions of the pie depend on personality.

Posted September 27, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Some people see equal distribution of wealth as fair, while others see distribution based on merit as fair.

- Evolutionary psychology explains instincts for both equal and unequal distribution of resources.

- Differences in perceptions of fairness are related to differences in worldview and personality.

Which of the two statements below would you agree with more?

a. Everyone deserves to have about the same amount of financial wealth.

b. People who are smarter, more creative, and more conscientious deserve more financial wealth.

Our feelings about what people deserve, what is fair, and what people have a right to are part of our personal moral psychology.

Some people feel that all human lives are equally valuable, and that no human being is significantly more important than any other human being. Because all lives are equally important, we are therefore all entitled to about the same amount of resources and wealth. From this perspective, giving everyone an equal slice of the pie feels fair, while dividing the pie unequally feels unfair.

Other people feel that some human beings deserve a larger portion of the pie because they are more valuable or important in some way. Perhaps they work harder or possess special skills that provide outsized benefits to the group (e.g., a medical doctor who can save lives). From this perspective, people who are exceptionally valuable or important deserve a larger slice of the pie, and failing to reward them with a larger slice of the pie feels unfair.

Evolutionary psychologists have provided explanations for both perspectives. Charleton (1997) describes research indicating that the millions of years that our human ancestors spent in cooperative, small-scale, egalitarian hunter-gatherer groups led to social instincts for equal sharing and distribution of resources. At the same time, we possess social instincts for status and nepotism that are evolutionarily older than instincts for egalitarian, mutual reciprocity. These instincts lead (primarily) males to compete for status, and those who successfully achieve higher status are accorded a higher share of resources that they are more likely to share with close biological relatives. The tendency of human social groups to stratify into different levels of status, power, and resources continues to this day.

Of course, the degree of the stratification of resources has varied over time and across geographic areas. Differential wealth and income across countries have been tracked by many organizations. People also differ in the amount of wealth disparity that they are willing to tolerate and in their approval of methods for accumulating wealth, but these are separate issues (Johnson, 2011). The focus of this post is on the tendency to favor equal or unequal distributions of wealth.

Whether our instincts favor equal distribution of resources or unequal distribution of resources according to status surely depends on a number of factors—an obvious one being where you currently stand in the status hierarchy. It is understandable that high-status individuals who already possess proportionately more resources want to hold on to their wealth and therefore feel that slicing the pie in unequal pieces is justified. In contrast, people with fewer resources who are struggling to survive understandably claim that the pie should be divided more equally.

At the same time, there are significant numbers of upper-middle-class Americans (and even some very rich like Warren Buffet) who want to radically reduce wealth inequality. What is the psychological explanation for this?

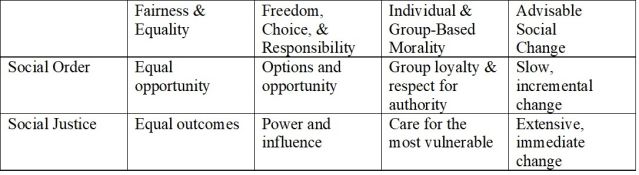

In a recently published book, John Iceland, Eric Silver, and Ilana Redstone (2023) argue that people tend to gravitate toward one of two worldviews that they label Social Justice and Social Order. Each of these worldviews entails "distinct ways of experiencing and thinking about human nature, the nature of social systems, social change, empathy, inequality, fairness, rights, responsibilities, agency, and the value of social practices" p. 10). Table 2.1 on page 26 of their book summarizes some of these differences. An adaptation of that table is presented below.

Iceland, et al. (2023) therefore explain feelings about the fairness of wealth distribution by showing how these feelings are embedded in one of two larger worldviews, Social Justice or Social Order. I could not help but notice while reading their book that these two worldviews bear a similarity to the Humanistic vs. Normative polarity described by Silvan Tomkins and the Dual Morality theory of Stephen Martin Fritz.

I also noticed that the Social Justice and Social Order worldviews are similar, respectively, to the Organismic and Mechanistic worldviews of Stephen Pepper. To test whether there might be overlap between Social Justice/Social Order and Organicism/Mechanism, I wrote three forced-choice items that represent differences between Social Justice and Social Order and added them to the end of the Organicism-Mechanism Paradigm Inventory (OMPI). The three items are as follows:

1. a. I want political leaders to protect established order and traditions in society.

1. b. I want political leaders to create progress and improvements in society.

2. a. When racism exists, it exists throughout the entire social system.

2. b. When racism exists, it exists only in individuals, not in the social system.

3. a. Everyone deserves to have about the same amount of financial wealth.

3. b. People who are smarter, more creative, and more conscientious deserve more financial wealth.

The responses scored in the direction of Social Justice are 1.b, 2.a, and 3.a. The three items intercorrelated significantly in an internet sample of over 3,600 individuals, and, if summed into a total Social Justice score, correlated a significant r = .24 (p<.001) with Organicism. The relation between Social Justice and Organicism is more pronounced if one contrasts the mean Organicism score from individuals who answered all three items in the direction of Social Order (N=188, mean=13.66, SD=4.57) with the mean Organicism score from individuals who answered all three items in the direction of Social Justice (N=1042, mean=17.10, SD=3.78). This difference is statistically significant, t(235.4)=-9.73, p<.001), but more importantly, a comparison of means to groups listed by Johnson, Germer, Efran, and Overton (1988) indicates that those oriented toward Social Order are clearly mechanistic, while those oriented toward Social Justice are organismic in their thinking. For comparison purposes, a US standardization sample had a mean score of 16.0 on the OMPI, while engineers and police applicants averaged 12.5 and 14.3 and psychology students averaged between 17.1 and 17.7.

Organismic individuals see the world as constantly changing and view human beings as naturally active, autonomous, self-transforming, and growth-oriented. Mechanistic individuals see the world as basically unchanging and view human beings as naturally reactive, controlled by their social environment, homeostatic, and fixed in their ways (Johnson, 1984). These views of the world are reflected in different personality tendencies. A battery of psychological tests indicated that organismic individuals are more intellectual, aesthetic, intuitive, liberal, experimenting, and changeable than mechanistic individuals. Mechanistic individuals were found to be more concrete, down-to-earth, sense-oriented, ordinary, conservative, and predictable. (Johnson et al., 1988). And we now know that organismic individuals are more likely to favor wealth equality, while mechanistic individuals favor wealth inequality based on merit.

References

Charlton, B. G. (1997). Injustice, inequality and Evolutionary Psychology. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 413-425. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200309

Iceland, J., Silver, E., & Redstone, I. (2023). Why we disagree about inequality. Hoboken, NJ: Polity Press.

Johnson, J. A. (2011, April). An evolutionary psychological analysis of intuitions about the fairness of wealth disparity. Poster presented at the 5th annual meeting of the NorthEastern Evolutionary Psychology Conference, Binghamton, NY.

Johnson, J. A. (1984, August). Personality correlates of the organicism-mechanism dimension. Paper presented at the 92nd Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Johnson, J. A., Germer, C. K., Efran, J. S., & Overton, W. F. (1988). Personality as the basis for theoretical predilections. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 824-835. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.824