Relationships

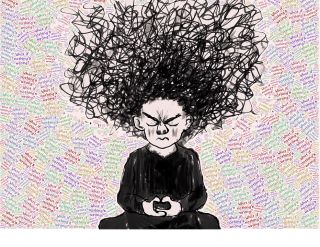

Do You Do Too Much for Others?

Feeling resentful is a clue that you've done enough, perhaps too much.

Posted July 19, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Doing things for others when they can manage themselves can be exhausting.

- Helping others may be temporarily required, but continuing after needs are met can be infantilizing.

- The person who does too much may not understand when enough is enough.

I recently facilitated a retreat for first responder significant others and spouses, all six of them women. They arrived exhausted and emotionally depleted. Tasked with jobs, raising children, some with special needs, and ministering to the needs of their traumatized mates, they had nothing left for themselves. They were isolated and lonely. Many complained that in doing for others, they had lost their sense of self.

People who can’t tell when they have done enough for others are partly people-pleasers, partly controlling, and perhaps partly conscientious to the point of perfectionism. They do for others when others could do for themselves, even the sick or disabled. Doing too much can be a learned habit—your mother did it for your father—or an unquestioned social norm that mandates women to be the ones responsible for keeping everyone in the family happy. Harriet Goldhor Lerner, author of The Dance of Intimacy calls this functioning “an individual’s characteristic style of managing anxiety and navigating relationships under stress.”

People who overdo:

- Give a lot of advice.

- Find it hard to listen to others in pain without doing something.

- Rush in to help before being asked.

- Find it hard to ask for or accept help.

There are many reasons for this behavior:

- To reinforce a sense of superiority. “I’m okay, you’re the one who needs help.”

- To compensate for a sense of inferiority. “I’m a bad mother or wife or husband; I will make up for it by doing everything for everyone."

- Because their parents were dysfunctional and they had to step in to take care of themselves and or their younger siblings. (This is frequently the case with first responders who have been rescuing others and solving their problems since childhood).

- Because life forces us to do too much in response to a medical crisis, a birth, or a death and we can't stop once the crisis passes.

- Because we're ashamed of our own needs or wishes to be taken care of. We hide them behind a veneer of being okay, competent, on top of things, and never needing help. Like the super on-top-of-it executive who has two rates of speed—forward or collapse.

- We are convinced that others would not survive without our help.

Finding the sweet spot between self-sacrifice and selfishness: We all need help at some point in our lives. Giving help is what friends and family do for each other. How do you know when you are doing too much for others? Ask yourself the following questions:

- Do I feel resentful over what I’m doing for others (and conversely not doing for myself)?

- Do others truly need my help (or so much of my help)? Could they do (fill in the blank) for themselves?

- Am I acting out of fear that I won’t be loved or I’m not good enough?

I got this: A story about the limits of doing too much: Arnie* was seriously injured in a fire. In the hospital, when Arnie was intubated and couldn’t talk, his wife Cara* learned to read his mind. Or so she believed. When he was released to recover at home, her entire sense of self rested on his mood. When he had a good day, she had a good day. When he had a bad day, she felt like a bad girl. Prior to his injuries, Cara was independent at work, but deferential when Arnie was home. After his injuries, she was deferential all the time.

Arnie’s recovery was challenging both physically and emotionally. He was obsessed with fire and triggered by the sound of helicopters. Cara was fearful every time she left the house, believing that if she wasn’t around, Arnie would be triggered, this would lead to chaos, everything would go to hell, and he would leave her. She didn’t know how to help Arnie psychologically. At the same time, she was convinced that if she could figure out how to stop his being triggered, he’d be happy.

As you can imagine, Cara was exhausted, resentful, and secretive. When she cried, she cried in the shower. She received a lot of praise for her competence and never had the courage to admit she was overwhelmed. Then she broke her leg. Now it was Arnie who had to help her. At first, she refused his assistance. “I got this,” she said and tried to suck it up. When Arnie was injured, Cara believed the responsibility for his recovery was both his and ours. But when she was the injured party, as someone who does too much, she believed recovery was hers alone. The more Arnie tried to help the more Cara felt like a toddler. The more she felt like a toddler, the more she understood that her helicoptering and hovering had made Arnie feel like a helpless child. With time and some counseling, Cara realized how out of balance their relationship had become and that Arnie, while still disabled, was capable of helping both her and himself, now and in the future.

Joined at the heart, not at the hip: Arnie was responsible for learning to manage his own emotions, his own medication, and ultimately his own recovery. Just as Cara was responsible for

- healing from her broken leg

- managing her unfounded and exaggerated fears that Arnie was totally incompetent

Through counseling and taking a long, hard, objective look at their relationship, Cara and Arnie came to realize that they were two separate human beings who were—as the saying goes—joined at the heart, not at the hip.

References

Lerner, H. 1989, The Dance of Intimacy: A Woman's Guide to Courageous Acts of Change in Key Relationships. New York, Harper & Row.

Kirschman, E. 2021, I Love a Fire Fighter: What the Family Needs to Know. New York, Guilford Press.