Media

The End of Reading

Why aren't college students reading—and what can we do about it?

Updated June 1, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- College students generally do not read books anymore.

- Reading is the best way to get better at writing.

- It doesn't matter so much what you read, just that you read.

- As an educator, I urge us to prioritize long-form reading so we don't regress intellectually.

Every year, my writing program hosts a summer seminar in which faculty members introduce new teaching strategies (e.g., what is ungrading and how does it work?) and share insights on new problems (e.g., how to manage student use of ChatGPT in college writing). This year, a colleague and I presented on a big and growing problem with teaching writing to the current generation of college students: They don't read.

The Chronicle of Higher Education featured an article on this topic recently.

I begin every freshman writing class by getting to know my students (our classes are small, which encourages discussion). I ask who likes to write and who doesn't; what are their writing habits and hacks; what was their experience with writing in high school, and more.

I also ask them, what's the best way to get better at writing? Invariably, they say, write more. In fact, that's the second-best way, I say. The best way to get better at writing is to read more. They don't like this. I hear things like, "I haven't read a book in ten years!" and "I haven't read a book since 6th grade!" or even, "I've never read a book."

This sounds crazy, I know. How can someone graduate from high school and get accepted into college without having read a book in years (or ever)? I have some theories, bolstered by recent research (see references below):

1) Technology: Generation Z (now in college) grew up with Google, cell phones, and social media, all of which provide quick and easy hits of information requiring lower cognitive loads than long-form articles and books.

2) Standardized tests: High school students are trained to inspect a paragraph in isolation and identify a thesis, a skill that's useful for the test but not for learning about human nature, the world, and how good writing works, which takes deeper, sustained reading.

3) Overscheduling: Middle school and high school students are increasingly overscheduled with homework, sports, jobs, music lessons, tutoring, and volunteering in the name of college prep and likely feel they don't have time for pleasure reading or even assigned reading.

The generational dearth of reading manifests in our students in several ways. Reading aloud in the classroom has become a dicey practice, with some students unable to sound out an author's unfamiliar name or pronounce even common words. They tend to write like they talk, with essays written in overly informal and casual language because they haven't experienced sufficient modeling from reading literature and academic writing. Here, I think of the input-output model of computing: You have to read good writing to do good writing. Lastly, emails from students are sometimes hard to decipher, as they're more like texts with abbreviations and no punctuation or salutation.

I want to stress that this decline in reading is a trend and not a rule. I'm always inspired to hear from students about a book they read over the summer and loved or a new, favorite author they discovered, and I had a student this past year who credited his strong technical writing skills to reading tons of automotive technical manuals. But the decline in reading is a growing trend, and it's not a good one.

A guest speaker at our summer seminar suggested that, in fact, college students read a lot, it's just that the content of their reading has evolved; now it's all texts, tweets, and social media comments.

Not so fast.

The kind of 'reading' people do on social media platforms is short, isolated, and information-based: I like this, I don't like that, you're wrong, I'm right, look at me, buy this, don't buy that. Collectively, these brief exchanges allow people to keep tabs on what everyone in the world is thinking about everything right now (which sounds exhausting).

Robust human brain development, however, requires something deeper than such quick hits of disconnected information. Sustained reading requires us to follow a line of thinking, to really consider and understand a point of view. We undergo deep learning as the new input reorganizes the neural connectivity in our brains so we can perceive the world in a genuinely new way. In other words, we learn when we read.

All academic subjects are important, since each one offers a piece of the puzzle to understanding ourselves and our world. But none of them, I would argue, is more important than reading, because when we know how to read, I mean really read, we can potentially learn and understand anything.

So, what can we do to improve reading skills in young people?

1) Find ways to limit superficial forms of reading (e.g., social media comments), which opens up more time for deeper forms of reading.

2) Consider that reading skills for test performance are important but not as fundamental to human development as deep reading to understand human nature and our world and live a more fulfilled life.

3) Consciously carve out time to read whatever strikes your fancy, whether it's automotive technical manuals or Plato's Dialogues. Young people need downtime and a reminder that downtime can mean a book instead of social media scrolling.

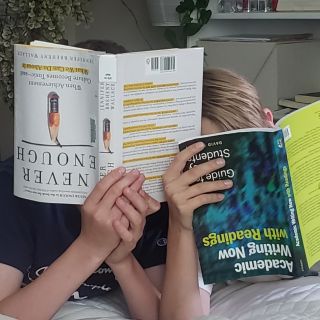

Currently, my middle school son and I are reading To Kill a Mockingbird together. We take turns reading aloud. Next fall, I'll read with my freshmen both the chapter on Generation Z in Jean Twenge's new book, Generations, and Jennifer Wallace's new book, Never Enough. I'm excited to see how my freshmen respond to these two excellent additions to contemporary literature on understanding this generation and helping them become the educated and informed readers, thinkers, and writers they want to become.

References

Twenge, J. M. (2023). Generations: the real differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents : and what they mean for America's future. First Atria Books hardcover edition. New York, NY, Atria Books.

Wallace, J. B. (2023). Never enough: when achievement culture becomes toxic-- and what we can do about it. New York, Portfolio/Penguin.