Child Development

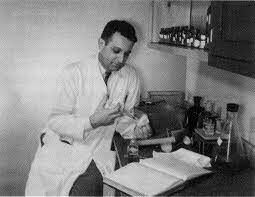

Dr. James Holland Dared to Take On Childhood Cancer

This medical pioneer headed the effort that turned the tide on leukemia.

Posted January 2, 2022 Reviewed by Pam Dailey

Key points

- The "Cancer Cowboys" were first to mount a nationwide effort against childhood cancer.

- Holland's way with words motivated others.

- His confidence that cancers could be cured led other doctors to want to work with him.

James Holland became a doctor thanks to what he termed “a series of fortunate mistakes.”

The son of a prominent lawyer in Morristown, New Jersey, Holland was raised to go into law, too. But all of that changed when he took a course in biology at Princeton University and became enthralled at seeing cells under a microscope.

“I was just captivated by what I saw,” he told me decades later. “Sometimes life works like that. Things suddenly turn, and you’re off and heading in a totally different direction.”

During the Korean War, Holland was in the U.S. Army. He secured an entry position at Columbia University, only to have President Truman extend military service time in 1951. When Columbia couldn’t hold the position for him, Holland went to nearby Francis Delafield Hospital, which had opened to care for cancer patients. Holland’s plan was to mark time at Delafield until a new slot became available at Columbia. Yet, like many of the so-called “Cancer Cowboys,” the early pioneers in childhood leukemia, he became intrigued with how to control this mysterious disease.

Holland was soon called to the National Cancer Institute, where he worked with Lloyd Law, one of the first doctors to use cancer drugs in tandem. With Law’s help, Holland began testing a combination of 6-MP and Methotrexate, which eventually proved successful.

In 1954, Holland arrived at Roswell Park in Buffalo, New York, brought aboard by George Moore, the facility’s flamboyant new director. Moore often flew his private plane to Albany, the state capital, to huddle with legislators and secure more funding. He was determined to hire young dynamic physicians to head the various departments at his growing hospital complex. Even though Holland wasn’t yet 30 years old, he was appointed one of three chiefs of medicine for the expanding cancer research facility. With the move, Holland saw his salary jump from $7,600 to $11,300 a year. He married Jimmie Holland, who would become a key player in the growing field of psycho-oncology, where psychology and oncology come together for cancer treatment.

Many consider this to be the beginning of a golden era at Roswell Park and for cancer research nationally. Holland’s contemporaries included Donald Pinkel, who was beginning to calculate better drug dosages for children with leukemia; Dr. Joseph Sokal and his staff developed new protocols for chemotherapy and Dr. Avery Sandberg investigated the role of chromosomes in causing cancer. There were plenty of egos in play, and Holland recalled that he and Moore “used to fight like cats and dogs. But we always respected each other.”

Back at the NCI, Gordon Zubrod asked Holland if he would continue to be involved in the leukemia program even though he was now in Buffalo. Holland agreed and took over many of the administrative chores for the collaborative effort. He was soon joined by Emil “Jay” Freireich at the NCI and Pinkel in Buffalo. In the beginning, Pinkel said it “was basically us four.”

This was inception of the Acute Leukemia Group B, which would later be renamed the Cancer and Leukemia Group B or CALGB. Members of the cancer research cooperative began to meet every six to eight weeks at the NCI outside of Washington, D.C., going over initial results and standardizing forms and clinical trial criteria. The Walter Reed Medical Center, the Medical College of Virginia, and the University of Maryland were among the other institutions to join the effort early on.

The ability to motivate people with words soon became one of Holland’s chief assets. In 1965, he published an article entitled, “Obstacles to the Control of Acute Leukemia” in the CA: Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Much of it had been originally presented at a symposium sponsored by the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute. The peer-reviewed publication was the most widely circulated oncology journal in the world, going out to more than 100,000 readers.

In the five-page piece, Holland cited the success of the combination of the Vincristine and Prednisone in the effort against cancer. Yet what got the medical world talking was the confidence, the sheer chutzpah, that Holland exhibited in his belief that childhood leukemia could be conquered in the years ahead. Despite the pessimism in many quarters, Holland insisted “that nearly every obstacle appears to be identifiable and approachable—if not surmountable—at present or in the immediate future.”

Jerry Yates was practicing medicine in southern California when he read Holland’s article. His initial reaction? “I need to talk to this man. I need to find a way to work for him.”

Yates had recently treated a patient who died of testicular cancer. The man was 27 years old, about the same age as Yates at the time. The young doctor was devastated by his patient’s passing. A few weeks later, Yates came upon Holland’s article. “And it just rocked me. It just snapped me out of this state I was in,” Yates said. “James Holland was so far ahead of the rest of us. He saw a different world out there—one of real possibility. One in which people could be, did we dare say it, cured? To hear something like that, when you’re working in many of the same areas of care…well, it meant everything to me.”

Holland died in March 2018, and Yates misses his good friend. “So much of where we are in terms of cancer research today goes back to Jim and his efforts, his determination to move forward against this disease.”

Growing up, Holland had been taught poetry by his father, and he found motivation and solace in the power of words. When I was researching my book Cancer Crossings, I once asked him if he would recite a few lines from a poem, perhaps a favorite of his.

“How did you know that about me?” Holland demanded. “That I knew poetry growing up?” I told him that I’d asked around, that many of his friends and peers admired this quality about him. “All right then,” he replied. “How about a few lines from ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.’ You know it?” I didn’t. “Well, you should. It’s one of my favorites. You can look up the particulars about it.” (Indeed, I found that the poem was written by Thomas Gray and published in 1751. It runs 144 lines, and scholars believe it was inspired by the death of Gray’s friend and fellow poet Richard West.)

Holland began in a confident baritone. A voice that did command one’s attention.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear,

Full many a flow’r is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

“I love the cadence of that, how it rolls off the tongue,” Holland said after reciting those lines. “I learned it when I was young, and I’ve never forgotten it. To me, it’s about believing good work can be done. How good work can be accomplished, if you’re willing to push on.”