Suicide

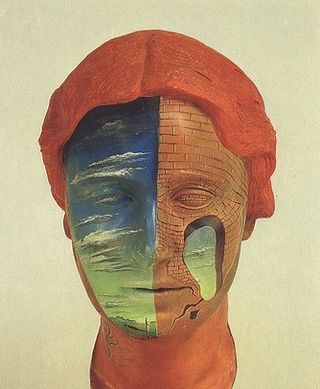

The True Self and the False Self

Which is which?

Posted October 12, 2017 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Kurt was a 22-year-old college student referred by his parents for depression and attempted suicide. He swung off a highway at full speed and was thrown from his car, but somehow survived without major injuries. The police arrived and booked him for a DUI.

Kurt was an only son; his parents were first-generation immigrants from Poland. His father was a chemical engineer and mother a mathematician.

Kurt attended a Catholic school in his elementary years and sang with the church choir. In high school, he excelled in math and, as you might expect, chemistry. Both parents planned his future, succeeding in helping him to get a scholarship at a top-ranked medical school, with the goal of his working in chemical biology.

Kurt said he didn’t really study much, but preferred to drink beer by the pitcher at the nearby pubs and sing rowdy songs. He also liked to visit the casinos to play roulette, winning more often than not, enjoying beating the odds.

“So why did you decide to take your life?” I asked.

“Because, while driving back to school from the casinos, I started having fleeting thoughts of suicide. I pushed back and tried to picture having fun at the casinos, but the closer I got to home, the fun feelings dissipated as I automatically geared up for life on campus,” Kurt replied.

I asked how long before his attempted suicide did Kurt have these fleeting thoughts. He said he wasn’t sure, but for at least six months. He said he hadn’t planned to kill himself but remembers hearing a faint suicidal thought, “OK, take him out.”

When asked if he had any idea where that voice came from, Kurt said no, but it was his from deep inside.

“I think you’re right,” I said, “that voice was from your 'true self,' the part that lay hidden, pretty much out of consciousness, since you were a child. You began taking on a false persona, encouraged and celebrated by your parents. The problem was that this “false self” began thinking it was your true self and delegated your true self out of sight/out of mind.”

“But why would my true self want to kill me?”

I pointed out that Kurt’s true self was the part that enjoyed socializing over beers and roulette at the casinos. But to prevent returning to the depths of despair and internal imprisonment, it decided to take out his false self, even at the expense of its own self, to prevent Kurt from continuing the charade.

“It all makes sense, but where do I go from here?” Kurt asked.

I suggested that Kurt could become his own person by beginning to make his own decisions about what career he wished to pursue, without necessary disregarding his parents' plans, but to evaluate the pros and cons and decide for himself. Not only would this provide for inner peace, but probably also enable him to find other ways to socialize and reduce his penchant for visiting the casinos.

“But I can’t do this to my mom and dad. They’d be heartbroken if I were to decide upon another career.”

“I’m truly sorry Kurt," I replied, "but you can’t have it both ways. Either you want to be your own person, or you want others, no matter how well-minded, telling you what to do for the rest of your life.”

Kurt said he would think about it. In the meantime, I told Kurt that I would talk to his parents if he wished.

I explained to both parents that Kurt had been suffering from an intrapersonal conflict that at a critical moment became so overpowering that it manifested itself in a death wish. On the one hand, he was driven by wanting to fulfill their dreams. On the other, he wanted to be true to himself, even if he didn’t know who he wanted to be in life. It usually takes a lot of trial and error to learn what we wish to make of our lives.

“You mean it’s our fault?” Kurt’s mother exclaimed. Kurt’s father motioned his wife to calm down and listen to what the “good doctor” had to say.

I advised them that it was no one’s fault, but actually quite common that, as children, the best way to survive is to please our parents. Then, somewhere around the age of 14 years or so, we begin to rebel, not for lack of love, but to find out who we are, what we truly believe—beyond just being an extension of our parent’s values and beliefs, however well-founded.

Kurt felt a special loyalty to and empathy for them both, for not being fully integrated and having a foreign accent that broadcast their not having been born in the states. He wanted to be proud of them and have them be proud of him. This led to his taking on a false persona, which prevented the rebellion necessary for him to grow and develop into becoming his own true person.

His father placed his hand on his wife’s shoulder while she was wiping away some tears, and said, “We have to let the boy go, Mama.”

“Yes,” I added, “let Kurt grow up and become his own man.”

*

This blog was co-published with PsychResilience.com

References

Laing RD (1963) The Divided Self, Pantheon Books, New York, NY