Motivation

Hungry vs. Loyal: Ramsay's Hounds on the Hierarchy of Needs

Game of Thrones villain Bolton thinks his deadly dogs' loyalty protects him.

Posted June 22, 2016

In "The Battle of the Bastards," the ninth episode of Game of Thrones' sixth season, sadistic villain Ramsay Bolton meets with the hero Jon Snow for parlay. When Jon makes it clear that he and his forces will not back down, Ramsay addresses Jon's companions: "And you're all fine-looking men. My dogs are desperate to meet you. I haven't fed them for seven days. They're ravenous! I wonder which parts they'll try first...." The character is talking about vicious, enormous hounds that he has used to hunt women for sport, that he had kill his stepmother and infant brother, and that he fed the corpse of the woman who hunted with him rather than let meat go to waste. He has taught them to see humans as both prey and food.

After a long battle that both tortures viewers when one dreaded thing happens after another and also surprises viewers with a triumphant moment or two, Ramsay sits bound and bloody in a cell in the final scene. Sansa Stark, who previously suffered much abuse at this sadist's hands, makes it clear that he is about to die. Two of his dogs enter the cell.

Ramsay: My hounds will never harm me.

Sansa: You haven't fed them in seven days. You said it yourself.

Ramsay: They're loyal beasts.

Sansa: They were. Now they're starving.

The hounds sniff and lick the blood on Ramsay's face, ignoring their master's commands to sit down and stop. His screams soon follow. Hunger soundly defeats their loyalty.

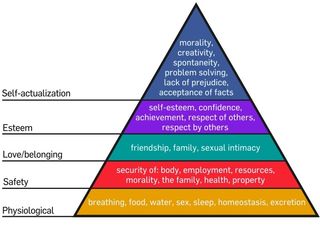

Looking at how human beings prioritize motives, humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow (1943, 1966, 1970) concluded that we advance through a hierarchy of needs, which is usually represented as a pyramid with the most powerful, fundamental motivations at the bottom. As Maslow saw it, each individual must make meet natural animal needs before making progress toward that person's potential as a human being.

Whatever loyalty Ramsay's dogs appear to have shown in the past may be because they associate him with shelter and other safety needs or because they feel actual connection to him (belonging or belongingness). Whatever loyalty they have shown in the past also vanishes when overpowered by starvation, and so do these animals who have learned that humans can be food turn and make a meal out of their master. Maslow said that the more biologically based need levels (physiological and safety needs) drive us through their deficits: We feel the need to alleviate their absence. Basic, survival-driven deficit of starvation takes priority over any other needs or associations Ramsay's dogs might carry.

Dogs can't really tell us much about people, can they? Oh, yes, they can. We all get hungry. Canine behavior might be harder to explain in terms of the highest levels of Maslow's pyramids. After all, how often does anyone discuss a dog's self-esteem or admire one for self-actualizing so well? Then again, though, Maslow's theory does not hold up as well at the higher levels (Miner, 1984; Tay & Diener, 2011). Maybe there's more animal to us all than the founder of humanistic psychology ever thought. People have reasons for saying it's a dog-eat-dog world, after all.

“Hunger turns men into beasts.” — Margaery Tyrell

episode 3-1 “Valar Dohaeris” (May 21, 2013).

Related Posts

- Ramsay Snow, a Sadist Dark and Full of Terrors

- Naming Evil: The Dark Triad, Tetrad, Malignant Narcissism

- Who Can Win the Game of Thrones?

- The Walking Dead Psychology: A Cannibal Conversation

- Serpents in a Happy Valley: Does the World Need Villains

References

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Maslow, A. H. (1966). The psychology of science. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). The farther reaches of human nature. New York, NY: Viking.

Miner, J. B. (1984). The validity and usefulness of theories in an emerging organizational science. New York, NY: Human Sciences.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354-365.