Fear

Halloween and the Mad Scientist Problem

Horror movies and the fear of science

Posted October 23, 2014

In search of novelties to bring to a holiday party, I recently dropped into a pop-up Halloween store in a local mall. It was a surprisingly large shop with rows of costumes, elaborate masks, makeup supplies, and party decorations, as well as a variety of tombstones, skeletons, and bloody bodies designed to create ghoulish yard displays.

Among the offerings at the Halloween store were several scary life-sized figures who, when placed on the porch or next to the door of the house, could easily terrify young trick-or-treaters. The offerings included your standard zombies—zombies are very popular these days—Freddy Krueger-style homicidal maniacs, and witches. But what attracted my attention were two motorized figures near the front of the store. One was a mad scientist replete with a dirty lab coat, a blood-stained surgical mask, and black wavy hair. When you pressed a button, the scientist began to gyrate and speak in a spooky voice: “You are in excellent health, so you will last longer in my experiments!”

It was a startling sight, and I imagine that—if encountered by a 6-year-old standing on a stranger’s porch at night—the scientist could be very scary. To make matters worse, the fellow standing next to the mad scientist was a poor captive, hooded in a manner disturbingly reminiscent of an Abu Ghraib prisoner, whose sole purpose was to be electrocuted. Pressing his button set off a cacophony of alarm bells, crackling noises, and buzzing sounds, as the poor victim began to scream and twist in pain.

Halloween is a kind of Rorschach test of our common fears, and the available evidence suggests our nightmares fall into different categories. For example, we are afraid of murderous people and monsters, but we find them particularly frightening if they have some kind of extra deficit. So, for example, zombies (an entirely fictional concept), as portrayed in contemporary movies and television shows—are fearful because, in addition to having the single motivation of gobbling up humans, they are amoral, soulless creatures, machine-like in their unwavering pursuit of flesh. In the case of common horror film villains, an additional creepiness is derived from a mixture of evilness and madness—amoral blankness and psychopathology. Thus the most successful of horror villains, such as Freddy Krueger and Michael Myers, combine both the absence of a moral anchor and the unpredictability of mental illness.

Of particular interest to me is the portrayal of scientists as fearsome crazies. Science and reason are supposed to be the antidote to paranormal beliefs, and yet fictional scientists often appear as villains of paranormal horror films. Why? Part of the explanation must be the addition of madness to the character of the conventional scientist stereotype.

Everyday examples of mental illness generally do not provoke fear. In daily life people suffering from mental illness in the community often appear more helpless and vulnerable than malevolent. In some cases, mental illness can even be associated with the positive traits. The time-honored belief that madness and genius go together appears to have some support. In her book Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, Kay Redfield Jamison traced the relationship between bipolar disorder and creative genius. Other research evidence shows that genius and schizophrenia can go together. But we tend not to fear people like Vincent Van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, or William Styron.

The villains of our nightmares possess a particular combination of psychological ingredients aimed at producing terror. The homicidal slasher movie monster is usually vicious—sometimes motivated by a twisted form of vengeance—and mentally ill. Mental illness makes the villain unpredictable, which alone might not be a problem, but someone who cannot be counted upon to adhere to the conventional norms of behavior and is hell-bent on killing as many people as possible is, indeed, scary. In addition, the homicidal slasher movie villain is often unusually strong, sometimes with superhuman abilities. So the fearsome triple threat is strength, mental illness, and a taste for blood.

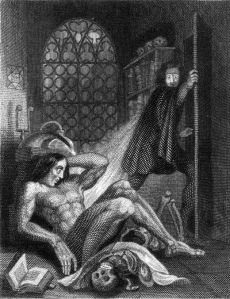

Frontispiece to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

The case of mad scientists is very similar, except that mad scientists get their power from brain not brawn. Dr. Frankenstein’s scientific brilliance produces monstrous power. In traditional portrayals, scientists are thought to have stolen forbidden knowledge from the gods or lost their humanity in some unholy Faustian bargain. Mary Shelley’s rarely remembered alternative title for Frankenstein was The New Prometheus.

In some cases, the scientist is not so much mad or immoral as possessed of inappropriate motives. In countless monster movies (e.g., The Thing, Alien), it is the scientist who wants to keep the creature alive for further study. Bad idea. These deluded researchers create conflict that moves the plot along, but usually the message is clear: the unbridled pursuit of knowledge is misguided, dangerous, and immoral. Better to follow the lead of the clean-cut, no-nonsense hero whose motives are focused squarely on the values of country, family, and public safety.

Of course, the real work of scientists often bumps up against legitimate moral and practical problems. Is it ethical to clone a human? What are the moral implications of research on human and non-human species? What are the costs and benefits of farming genetically modified fish?

Sadly, irrational fears about science are not just in the movies. Fear of science is seen in some of the more extreme claims made in opposition to genetically modified organisms. Fear of science also feeds an anti-vaccination movement that has led to a modern epidemic of whooping cough and measles.

The mad scientist of movie fame is an enduring stereotype that is probably harmless. But the fear of science is a real problem. It devalues the work of thousands of dedicated researchers working in the public interest.

Perhaps the most serious problem for the image of scientists is not the mad scientists of the movies, but the commercially-motivated scientists of big business. As long as there is a profit motive driving technological innovation in areas that directly affect our health and safety—such as agriculture and pharmaceuticals—it will be easy for the critics of these industries to make scientists into deluded soulless Fausts. Indeed, this is a common theme of modern science fiction movies. In Scott Ripley’s Alien, it is Ash, the Science Officer (later revealed to be an android), who attempts to keep the alien alive and return it to the company for possible commercial use.

Science’s contemporary image problem may just be another feature of a larger political challenge: finding the right balance between private business interests and the public good. Between free trade and healthy living. Science can make contributions to both spheres. But, as long as business interests motivate the work of scientists, the somewhat mysterious power of science will remain suspicious.