Empathy

Why Do We Wince When We're in Pain?

Scientists have discovered that animals also wince, giving clues to its purpose.

Posted September 12, 2016

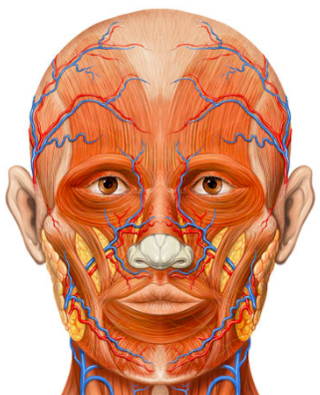

Facial expressions are a unique feature of mammals. No other group of animals has anywhere near the capability that mammals have to shape and contort our faces.

In fact, mammalian facial muscles are quite peculiar as muscles go. Normally, muscles are attached to two different bones on either end and then draw those bones together as the muscle shortens during contraction. Facial muscles are weird because they attach to bone on one end and then soft tissue on the other. They don't move bones around; instead they pull, scrunch, and squish the skin of our faces. And why? To communicate, of course.

But first, we have to back up. The strange configuration of mammalian facial muscles did not evolve in order to facilitate facial expression. As so often happens, this is an exaptation, a new function for something that evolved for a different purpose altogether. Just like feathers did not evolve to help animals fly, facial muscles did not evolve to allow mammals to make facial expressions.

The original purpose of facial muscles was for suckling during breastfeeding. This explains why only mammals have these strange muscles - only mammals have breasts. (Mammal comes from the latin "mamma," meaning breast.)

Although they were not the original function of facial muscles, facial expressions almost certainly evolved quickly thereafter, given how universal they are among mammals. As discussed in my book, most mammals have just a few basic expressions. However, the diversity and complexity of facial expression really explodes in the primate lineage and, like most other forms of communication, makes another great leap in complexity in humans.

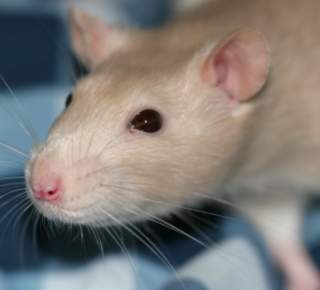

In 2010, researchers in Montréal discovered that mice display a characteristic facial expression when they are in pain. By using mildly painful stimuli and recording with high-speed video cameras, the researchers were able to document and code five facial movements that were almost always elicited when the mice were in pain. The mice close their eyes and scrunch the skin around their eyes. Their nose and cheeks bulge outward and backward (toward the eyes), their ears move backward, and their whiskers twitch.

The researchers observed these responses with a variety of painful stimuli, and the responses were proportional to the severity of the pain. The pain was not focused on their faces, and yet, their faces were reliable indicators of the pain. When the researchers administered a pain reliever prior to the painful stimulus, the facial expression was measurably reduced.

I was struck by how similar the mouse facial response to pain is to the human one. When you factor in the shape differences in mouse and human faces, the mouse response to pain is almost exactly the same as ours. When in pain, we squint. The muscles in our cheeks ball up, and while we don’t have whiskers, we do usually scrunch up our noses.

We are separated from mice by about seventy-five million years of evolution, and yet, we make the same face when we're in pain. (If you are wondering why these experiments were done, the research group studies pain and is searching for therapies for human sufferers of chronic pain conditions.)

Since then, the pain grimace has also been discovered in rats and is basically the same as in mice. "Pain faces" have also been found in rabbits, lambs, horses, pigs, and rhesus macaques. Because so many mammals exhibit the same pain wince, it must be inborn, not learned. (To be sure of that, the study with mice was done with infants.)

The question remains, why do we have an involuntary behavioral program that causes us to wince when we are in pain?

Does the wince somehow mitigate the pain, like when we rub our head after bumping it? It doesn’t appear to.

Could the wincing offer some strategy to avoid the painful stimulus? I can’t see how.

Is it just an accidental by-product of neurons that are spontaneously activated by the incoming impulses relaying the pain stimulus? Nope—the sensory perception of pain and the motor activation of facial nerves are housed in totally different parts of the brain and carried by different nerves.

The only purpose that has been suggested for the pain grimace is that of communication. By grimacing, an animal is actually giving a signal to nearby pals. Watch out! This thing hurts!

Assuming that the message is received, this communication has great value because something that is painful is also usually dangerous. In fact, that is how and why pain evolved in the first place, as a means to train animals to avoid things that can cause injury or death. (Pain also immobilizes us after an injury to allow healing.) In nature, pain equals danger, so it stands to reason that social-cooperative animals would evolve a mechanism to communicate pain as a means to signal potential danger.

Because we’ve only just discovered the pain grimace, the communication-of-danger hypothesis has yet to be tested definitively. It also may hinge on group-selective forces, which are dubious in evolutionary theory.

However, a different communicative function of the pain grimace has already been proposed and more or less proven. By grimacing, infants communicate their discomfort to their mothers or other caregivers. This is akin to crying but more subtle. In humans, we interpret babies’ signs of distress and pain using logic and common sense, but animals have been able to understand and meet the needs of their young long before us. Perhaps the pain grimace plays a role in that. Interestingly, suckling has been shown to relieve pain in infants, even when the pain has nothing to do with hunger per se.

The discovery of the pain grimace in many other mammals only emphasizes the likelihood that emotional communication long predates humanity and was refined over many millions of years of evolution. As discussed in chapter 3 of my book, empathy and communication are almost certainly intertwined because empathy is communication.

[This article is an adapted excerpt from my book, taken from chapter 10: The Richness of Animal Communication.]