The statistics are astounding. As I write this, the current COVID-19 death toll in the United States is over 500,000. Worldwide, more than two and a half million have perished, with 111,545,709 confirmed cases and counting.

While I have friends who have survived the severe illness caused by the virus, I personally don’t know anyone who has died. And yet when I think of the two and a half million people who are gone, and the countless millions more who are grieving the loss of a loved one, a friend, a neighbor, a co-worker, or an acquaintance, my heart opens and my mind implores, “What are we supposed to be learning from this cataclysmic world event?”

I would like to offer what I have been learning and continue to grapple with personally. As a psychologist, I see this same challenge repeated over and over in my clients, and in my circle of family and friends.

Looking within

When the pandemic struck, exactly one year ago, health officials exhorted us to “Shelter in place.” For me, this triggered an anxiety-ridden memory of being terrified as a child, during the heat of the Cold War in the mid-'50s, when my parents refused to build an underground bunker —a bomb shelter—to which we could run and hide from the ravages of nuclear war. This led to another scary, even earlier memory: During the Korean War, we had drills in my first-grade classroom to jump under our desks — to shelter in place — when we heard the piercing civil alert siren, signaling an imminent bomb attack.

Fifty years later, in 2020, the command to “shelter in place” was to stay at home, and, for many, the challenges have been severe. One friend (a therapist) and his wife (a third-grade teacher) have to work from their bedroom and kitchen at the same time organizing their three young children to attend different Zoom schools. That’s five computers, simultaneously online, in one household. And the countless people who have lost their shelter altogether: evicted from their apartments, saw their homes go into foreclosure, and were forced to live on the street. The number of “tent cities” has become a visible, socially induced, metastasizing cancer, with people forced to live in various degrees of abject poverty and squalor.

Yet I saw another, deeper meaning to “shelter in place.” To me, it signaled “go inside,” not just in our homes, but within ourselves, We couldn’t go to work or to school, shop, go to restaurants or bars, or travel on public transportation. We couldn’t go to parties, weddings, or even funerals.

Cut away from these, call them external, trappings of “normal” life, what are we left with? We are forced to keep company with ourselves. While this was a novelty at first, it soon became an inconvenience, a drag, and something to complain about. For some, it prompted an opportunity to rebel: “I’ll go wherever I want,” and “No one can force me to wear a mask.” People longed for life to return to “normal” or a “new normal” until we started wondering what that would look like, and what, indeed “normal” actually signified. Didn’t it really mean “what we had grown accustomed to?"

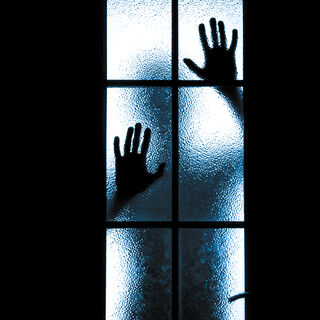

What happens when all of that — all of what we know, are familiar with, and depend on — is shorn away? What happens when we are left alone, psychologically naked, with ourselves?

Forty-five years ago, I took a long solo trip around South America. At first, it was all exciting. I remember walking around Rio de Janeiro thinking, “Wow, kids wear braces here,” or seeing Cool Whip in a Buenos Aires supermarket and remarking to myself, “Just like home!” But the novelty soon wore off. I knew no one and spoke no Portuguese or Spanish. There was no connection to anything or anyone. I was utterly alone, forced to confront all the negative thoughts and feelings I had about myself and about life. My own shadow had become my uninvited, unwanted, smelly traveling companion. I was a walking prisoner inside myself. I was tormented, I broke down.

We are definitely not accustomed to self-confrontation. To be alone with our thoughts and feelings, our fears and resentments, our inner fantasies and miseries, without continual distraction and escape, is to be relentlessly and helplessly sucked into the quicksand of negativity that many carry around inside without realizing it. “Go inside”— the psychological version of “shelter in place”— has forced us to look at the continually disturbing detritus of our inner dwelling, and it’s not pretty.

Yet, it is possible to see the opportunity in this self-confrontation. To witness how identified we are with everything that is ephemeral, and how little we are consciously connected to what is eternal. In the recently published book, Sovereign Self, Vedic teacher and scholar Acharya Shunya, points out “ ... you have become a worldly defined and limited persona, estranged from your own source. As a worldly body you live, eat, opine, dream, sleep, love, achieve, fail, compete, age, make love, complain, delight, suffer or enjoy.... but all along remain ignorant of your Self, which is inherently whole, powerful, joyful and of the nature of unconditional love.”

Practicing compassion and contribution

While self-confrontation and self-knowledge are not taught in our schools (and should be), we each have the opportunity to use this time to explore our inner garden, pull the weeds, lift the rocks, replenish the soil, and come into the fullness of who we really are — loving, compassionate beings who share this planet—our home. When seen in this light, the pandemic, caused by a microbe that knows no borders, boundaries, races, or religions, is not only the great equalizer — we are, all of us, simply human beings—but it may also be the great mobilizer to help us realize that we all share this human experiment. That we, each of us, have a responsibility to cultivate our garden, our green planet, so that, everyone can be fed and nurtured, physically, psychologically, and spiritually.

The fourth-century rabbi Hillel, said this: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?”

This is our time — to realize our true potential, not as select individuals amassing unseemly amounts of wealth while others starve — but as a collective community in which each of us contributes to the greater good. When we “go inside” and do the necessary housecleaning, we can emerge as givers, not takers.

References

Archarya Shunya, Soverign Self: Claim Your Inner Joy and Freedom with the Empowering Wisdom of the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita (2020). Sounds True.