Empathy

Thinking About The Unthinkable

What makes us human? And why does it matter?

Posted June 7, 2012

In the 1990 movie, Awakenings, there is a scene that I’ve always found chilling. In it, Dr. Malcolm Sayer, a fictionalized character based on Dr. Oliver Sacks, visits with an expert in an attempt to understand the condition (post-encephalitic parkinsonism) of a number of the patients in the chronic hospital where he works.

These patients were survivors of an outbreak of encephalitis lethargica that occurred between 1915 and 1926. As they watch old filmstrips of patients the expert has seen, he explains what happened to those who survived the acute stages of the infection:

“Those who survived, who awoke, seemed fine, as though nothing had happened. We just didn’t realize how much the infection had damaged the brain. Years went by – 5, 10, 15 – before these strange neurological symptoms would appear, but they did. I began to see them in the early 1930s. Old people brought in by their children. Young people brought in by their parents. They could no longer dress themselves, or feed themselves. They could no longer speak in most cases. Some families went mad. People who were normal, were now, elsewhere.”

Standing there, watching these human beings on the screen, unable to move or communicate, Dr. Sayer asks: “What’s it like to be them? What are they thinking?”

“They’re not.” The expert retorts, “The virus didn’t spare their higher faculties.”

Disturbed, Dr. Sayer challenges. “We know that for a fact?”

The expert’s response is once again direct and affirmative, but Dr. Sayer continues to challenge: “Because?”

To which the expert responds, devastatingly: “Because the alternative is unthinkable.”

The expert’s response, to some, may be understandable. Some may even look at is as empathetic. After all, he IS putting himself in the shoes of the patients, imagining what it must feel like to be them. Clearly, he doesn’t like what he sees when he does so, and therefore rejects it. But, I can’t look at it as empathic. Not really. Why?

It’s the easy way out.

Rejecting the imagined reality of a condition that the he found to be repugnant paved the way for devastating consequences for the patients in question. When you don’t believe a person thinks, or is sentient, it is the doorway for believing that they are not human. And believing that they are not human is part of the reason for what happened to these patients in real life.

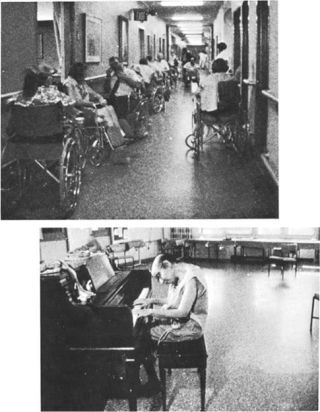

The world turned their back on them. Wrote them off. Relegated them to institutions where only the most dedicated of family members would visit, or care. Warehoused, as Diane Sawyer once put it, like “human furniture.”

In the book of the same name, Dr. Sacks, the real doctor behind the fictionalization, stated that some of his patients “had achieved a state of icy hopelessness akin to serenity.” Abandoned by friends and family, they were “profoundly isolated” and “deprived of experience.” An unthinkable outcome for the sentient beings they indeed were – and attitudes that rejected their sentience were part of what allowed it to happen. Why visit someone whom experts tell you is essentially “dead,” a human statue?

Some may wonder, what this may have to do with autism…well, for me, it has everything to do with it. I see these types of dismissive attitudes all around the autism community. In many circles, the discourse around autism is all around what isn’t there, and what autistic people “can’t do.” And it leads to devastating results.

Take, for example, an encounter I had some years ago. One afternoon, I found myself speaking with a young woman who worked with youth, many of whom had special needs. As we made small talk, I asked her to tell me about her job. She sketched her experiences with broad strokes, in the typical way you do with someone whom you don’t know very well. Then, she suddenly turned to me with great animation. Grabbing my arm, she burst out, “And I HATE the autistic ones!! They BITE.”

My world stopped. The attack was so sudden, and virulent, it literally took my breath away. Appalled, I opened my mouth to speak and found that I couldn’t. Such is the cruelty of losing speech under stress. You lose it when you need it most. Of course, she had no idea she was speaking with an autistic person, which is one of the curses of having a less visible version of the condition. You get a front row seat to the real feelings often edited, the ugliness the people put on display when they think nobody is listening, at least nobody who cares.

By the time I recovered myself, the shifting sands of the social situation had gone on without me. To this day, though, I can remember exactly what I so desperately wanted to scream at her that day: “Do you KNOW how much pain a kid needs to be in in order to strike out like that!?” But, many people don’t look at it this way – it doesn’t even occur to them. Because, according the opinions of many educators and experts, autistic people can’t show empathy. What follows is the assumption that a person striking out, like the children this woman described, do so because they simply don’t know (or don’t care), about the impact of their behavior on the other person.

But there is an alternative explanation. Pain.

I look at it this way. In any interaction, there is an equilibrium between pain and empathy. Most human beings, autistic people included, do not want to harm others. This concern, however, is often balanced against the amount of pain we experience. For example, a person whose hands are being burned by thick, scalding soup may forcefully shove another person out of the way to get to the sink so that they can run their burned hands under cold water. Few would judge them for this. The person shoved may not like it, and may wish they found a less hurtful way to handle the situation, however they recognize that the person was acting to alleviate acute pain, and remove themselves from further harm. That their empathy was overwhelmed by urgent need.

Unfortunately, many times in the case of a person with autism, the pain and harm that they are going through is not externally visible. With no frame of reference to the world that the autistic person lives in – in which seemingly innocuous things like the buffet of a fan can feel like sandpaper, an accidental bump can feel like blow, and the bark of a dog can feel like a kick to the head – the idea of pain is easily discounted or underestimated by a neurotypical observer. Especially of the person in question has difficulty with verbal and nonverbal communication.

If a person can’t tell you they’re in pain, and their body language doesn’t show that they’re in pain, how would you know that they are? If you felt like someone was hitting you, wouldn’t your first instinct be self defense? Especially if you had no other means to ask the person to stop?

To me, it would seem like the solution to such a situation would be not to hate the person, or judge them for behaving in a way that many people would in similar circumstances, but to work to figure out the source of pain, and help the person to find a different, less harmful way, to communicate it in the future. Doesn’t that make sense? And, in fact, if their pain and stress levels are chronically high, wouldn’t it, in actuality, take MORE empathy to keep that equilibrium in balance?

The idea that certain people lack qualities that “make us human,” whether it’s sentience, or empathy, is one that’s caused profound damage over the years in many contexts. Researchers may speak about it in theory, but in practice, the idea that autistic people lack empathy has the dangerous impact, among other things, of reducing empathy toward the pain of autistic people.

Recently, the news broke that the UN is calling for an investigation of a Massachussets special needs school for torture, after a law suit led to the release of disturbing video of a young man being shocked with electricity 31 times over a period of 7 hours. If we assume that behavior is communication, and that “problem behaviors” are often attempts to communicate stress and pain, then what does it mean when we “treat” such behaviors in this way? Does that make sense? More to the point, is it humane? Or is there a better way?

Effectively including those with disabilities into the community requires that we prevent the mistakes of the past. How do we do that? We need to presume competence. Presume sentience. Presume humanity.

Why? Given the implications, the alternative is unthinkable.

For updates you can follow me on Facebook or Twitter. Feedback? E-mail me.

RELATED READING

- Morton Ann Gernsbacher: On Not Being Human (Association for Psychological Science)

A few years ago, I was at a conference on language and evolution when an audience member questioned a prominent child language researcher’s thesis by raising a counterexample: One aspect of the development of children with Williams syndrome didn’t quite fit the researcher’s theory. The prominent child language researcher quickly retorted, “Oh, I’ve seen children with Williams syndrome. They don’t count. They’re not even human. They must belong to some other species entirely.”

With the wave of a hand, an entire group of people erased from the human race. Without a contesting word, members of the human species were sacrificed — but a theory was saved.

- Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg: The Empathy Issue Is a Human Rights Issue

Empathy. For most people, the word is synonymous with humanity.

The American Psychological Association calls empathy “the trait that makes us human. According to author D.H. Pink, empathy is “a universal language that connects us beyond country or culture. Empathy makes us human. Empathy brings joy…. Empathy is an essential part of living a life of meaning.”