Left Brain - Right Brain

Visual Journaling: An Art Therapy Historical Perspective

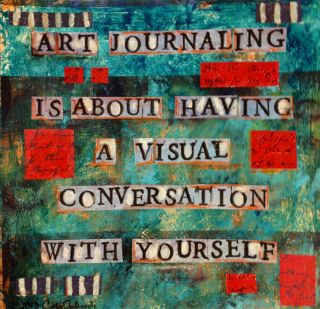

Art journaling is about having a visual conversation with yourself.

Posted October 30, 2013

Image and quote @2013 Cathy Malchiodi

Because of its history in art and psychiatry, visual journaling (aka art journaling) is one of the basic methods used in art therapy (see “Top Ten Art Therapy Interventions). As I said in my previous post, visual journaling is used in a variety of ways including as a means of reducing stress and emotional self-regulation. In terms of psychological trauma, visual journaling is also embraced as a practice that capitalizes on right brain dominance and supports meaning-making.

While there are many individuals in art therapy and related fields that can be referenced on the topic of visual journaling, one in particular stands out from a historic perspective. Several decades ago, art therapist Lucia Capacchione envisioned a form of visual journaling called “creative journaling.” My well-worn copy of her initial book on creative journaling is one of the oldest books in my art therapy library and is one I keep returning to. Like many art therapists, Capacchione shares that she was influenced by Carl Jung’s Man and His Symbols; she also reports that Anais Nin’s Diary had a profound affect on her and her subsequent investigation of art-based journaling methods. And like many who find comfort in journaling at times of trauma and loss, Capacchione clearly underscores that her journaling, both in word and image, was born during a period of personal crises.

The techniques Capacchione presents are deceptively simple and these same techniques are often applied in art therapy today. Her drawing prompts include creating simple images of “how do I feel right now,” “what do I feel on the inside and what do I show to others on the outside,” and “what would my self-portrait look like today.” There are many other directives in Capacchione’s original set of prompts, including drawing mandalas, dreams, timelines and various life experiences. In brief, these visual journaling prompts help to make visual one's pictorial vocabularies and with the facilitation of a therapist, increase awareness of the personal narratives our images and symbols manifest. But out of all these prompts, two in particular stand out and are still part of art therapy theory, methods and historical lore today.

The first is drawing and writing with your non-dominant hand, a prompt that eventually became the author’s signature technique. Capacchione’s claim is that this way of drawing and writing brought forth a sort of wisdom from the right brain and even one’s “inner child,” terminology from then popular transactional analysis and subsequent “child within” therapy for adult survivors of childhood abuse. At the time art expression and creativity was widely promoted as basically a right brain activity, a loose interpretation of the findings of Nobel Laureate Roger Sperry who pioneered research on hemispheric functions of the human brain. In brief, Capacchione proposes that writing and drawing with the non-dominant hand provides more access to right brain functions like feeling, intuition, spirituality and creativity.

Today we are more savvy about the complexity of the brain and that creative expression is a whole brain activity, not a solely right hemisphere accomplishment. And primitive handwriting and drawing with one’s non-dominant hand is not necessarily an automatic doorway to one’s inner child, no matter how child-like the images or scribbled letters that appear on paper. However, these techniques when explored via visual journaling do provide a spontaneous form of expression that helps individuals let go of control and judgment about creative output. I often use this approach with individuals as a warm-up or as an uncensored way to experience drawing as a form of self-exploration. There is evidence that cultivating the use of one’s non-dominant hand may have an integrative effect; for example, musicians who use both hands have an increase in the corpus callosum, the part of the brain that connects the two hemispheres. So theoretically, using both hands may create more transfer between the two sides of the brain. There is also evidence that using both hands to scribble or draw is an integrative experience and at the very least, gives the brain a different type of sensory and cognitive workout (see McNamee's research in the Reference section below).

The second concept that was novel for its time period involves Capacchione's use of visual journaling in conjunction with making an intention. The act of "making an intention" can easily take on a fluffy connotation involving candle-lighting, wishful thinking and mysticism. Art journaling is by no means the royal road to intentions coming true. But when using art expression to make visible and tangible a positive intention for oneself, I believe that Capacchione was on to something. Today, proponents of the value of intention in therapy describe it as a form of cognitive reframing and resilience-enhancing behavior. Creating an expression to represent an intention and reinforcing that in regular visual journaling not only serves as a reminder, it is also an imaginal commitment to change. Because art expression is a whole brain activity that capitalizes on non-verbal, sensory experiences, it is possible that when we draw and write about positive intentions, we increase the chances of behavior change or at least establish what we intend in a deeper, more complete manner.

I encourage you to get yourself an art journal or even a composition book at the dollar store, grab some felt markers or Sharpie® pens and try some of the techniques described in this post. The next installment of this series will describe some more visual journaling techniques, 21st century art therapy influences and what we know via research about best practices.

Keep calm and art therapy on,

Cathy Malchiodi, PhD, LPCC, LPAT, ATR-BC

© 2013 Cathy Malchiodi

References and Resources

Capacchione, L. (1988). The power of the other hand. North Hollywood, CA: Newcastle. [re-released in 2001]

Capacchione, L. (1979). The creative journal: The art of finding yourself. Chicago: The Swallow Press. [re-released in 2001]

McNamee, C. (2005). Bilateral art: Integrating art therapy, family therapy and neuroscience. Retrieved at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10591-005-8241-y.

Nobel Laureate Roger Sperry and the split brain experiments, see http://www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/split-brain/background.html.