Identity

Re-humanizing thru Art —Pressing On with the Discourse

How art can reverse the “natural” oppression and dehumanization of prison

Posted December 20, 2016

The most recent post presented my introduction to an address I gave at the Canadian Art Therapy Association/Ontario Art Therapy Association annual conference in which the theme was Art Therapy and Anti-Oppressive Practices. In this post I explored my identity in the context of oppressive relationships and actions. Thank you all to those who responded to the post; the many who responded positively and the few with vituperative glee; this signaled to me the need to continue this conversation. [And for the person who indicated that my last blog demonstrated that I was intellectually bankrupt, I wish to restate what I said in my comments-- I would argue that I am not really intellectually bankrupt--perhaps my account is overdrawn at times, but am not yet ready to declare bankruptcy.] This post, reiterating much of what I said in the Canadian address, carries with it a different type of awareness and call for action.

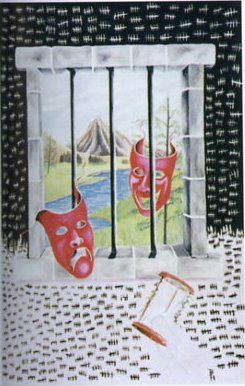

Commonly, most people don't consider prison inmates to be “oppressed”—they committed a crime, they are arrested, and now they are serving their time. However, given the nature of the system, oppression remains pervasive.

I believe this occurs prior to prison as well as within. Some may be inside because of how they are perceived and received by the greater society; not just because of their crime, but because of other factors, including where they live, the color of their skin, the god to whom they pray. Some have posited that they were previously in repressive situations, saw no way out, committed a crime, and ended up in prison, perpetuating a cycle of oppression. This is not denying that those who commit a crime should be punished; the justice system is established to protect society and penalize those that break the rules. However, some argue it is easier for select people to find themselves within the justice system because of who they are as much as for what they did [Becker, 1963/1991; Sagarin, 1975; Spector & Kitsuse, 1973]. Those who wish to posit this argument indicate the well-documented racial inequality inside as compared to the population outside.

As just one example among many, Howard pointed out the pervasiveness of African-American men who end up in prison:

“Even today, such staggering numbers paint a sobering reality which suggests that a young African American male who starts kindergarten in the fall of 2006 has a better chance of finding himself under the supervision of the penal system or being incarcerated than enrolling in a college or university twelve years later” ( Howard, p.959)

37% of the prison population is African American, significantly higher than the 12% that make up the general population [Carson, 2015].

Thus, some may be seen as twice oppressed- prior to their arrest, and again in prison.

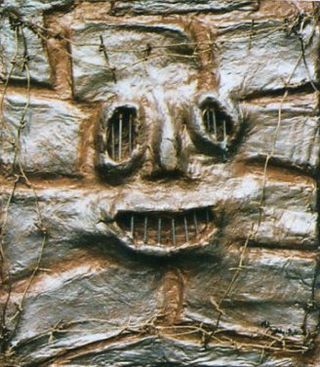

Once inside, the oppression is perpetuated. Security is obtained through the objectification and infantilization of the inmate; of making them less human (Fox, 1997). As I argued in yet another post [title—link], their identity is stripped away, and they are given a number and uniform, reinforcing their loss of self and disempowering them, all in the name of safety and security.

Never mind that such acts further reinforce their separation from society, making it challenging to reintegrate once given the chance.

They often struggle to knock off the label they have been given, making it difficult, at times impossible, to be re-accepted by society.

As a result, inmates personify the most vulnerable, the disenfranchised.

Giving them a voice, a new sense of self, would empower them to rise above the oppression that makes it difficult for them to adapt and succeed.

Art can help.

Interactionism

Over the years of providing art and art therapy services in prison, my epistemology has shifted from a psychological to a sociological lens—specifically, a Social/Symbolic Interaction perspective.

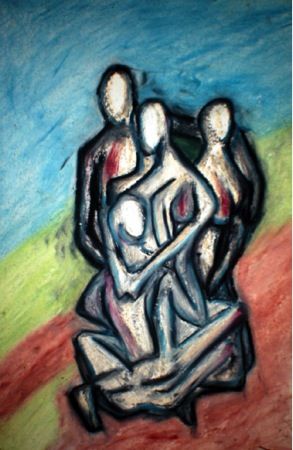

Simply put, this perspective contends that who we are and how we see ourselves is contingent upon who and what we interact with [Becker, 1991; Blumer, 1969; Cooley, 1964; James, 1890/1918; Mead, 1964]. There exists an interdependence between the social environment and individuals, and a person's self identity emerges from society's interpersonal interactions and the perceptions of others [Cooley,1964].

Within this theoretical perspective lies labeling theory—labels are established and solidified by those dominant within a society—the majority labels the minority; in other words, cultures decide who is deviant. Once someone is labeled as such, a new identity is created; the person thus labeled accepts this new identity and the real or perceived deviance is reinforced and amplified (Becker,1991).

Thus, it’s easy to follow this to its logical conclusion--once an inmate always an inmate.

I would argue that the reason that recidivism is so high is because they are seen as—and more importantly, see themselves as—prisoners.

Interactionism and Art

Symbolic Interactionism also contends that interactions may not be just between the members of a community but may in fact be between people and objects. Artifacts have meaning for people, meaning which is “. . . not intrinsic to the object but arises from how the person is initially prepared to act toward it” (Blumer, 1969, 68-69].

The sharing of such objects, and the interpretation thereof, define and shape an interaction, thus helping create relationships and new meanings.

Such objects include art, produced and viewed by members of the society {Becker, 1980).

Art makers can become meaning makers.

This statement almost becomes the defining maxim for many of these posts. Within the prison walls, as it is in most cultures and societies, art and art making takes a hierarchical precedence. Those who make art are held to a higher level [Dissanyake, 1992; Kornfeld, 1997) by both the inmates and the correctional staff.

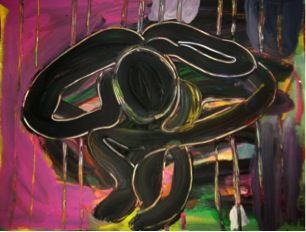

In creating a bridge between the inside and the outside cultures, art has the power to re-humanize the dehumanized. An art piece is an extension of the artist—it comes from within. It is a true reflection. Thus, if one accepts an art piece from an inmate, it signals that the inmate is in turn, accepted. It makes him real. It makes him “a person”—a creative being. And, in turn, has the power to reverse the oppressive practices.

A previous post, “Making Something Out of Nothing”, stressed how making a particular art piece can go a long way to re-developing and reinforcing new identities, above that of inmate. The very act of making these very simple pieces overcomes the negative labels and objectification placed upon them by the controlling environment. This allows a true person to emerge, one that is not identified as merely a deviant of society but rather a person capable of rising above his actions and perhaps even succeeding upon release.

Recently, a graduate student, Casey Barlow, who spent the most recent semester working in a local men’s prison, asked one of her clients “What if anything, did you get out of this experience?” The inmate’s response was formidable; his eyes lit up, he sat upright, and he enthusiastically exclaimed, “Oh that’s easy—now when I look at myself, I know that I’m not that bad.”

Sometimes, that’s the best place to start.

Postscript: After three and half years and over fifty posts, including those written by some wonderful colleagues and friends, other personal and professional projects have demanded more of my time and energy. As a result, while I work on a new book project and pursue expanding art services in the state prison system, I will be placing this blog on an indefinite hiatus. While I leave open the option of visiting it from time to time, I believe the time has come to let it rest.

I am grateful to all of the readers for supporting this work, and for all of those who took the time to write comments—both positive and negative—continuing the dialogue and reinforcing its ideas through acceptance and challenges. Art therapy in forensic settings has grown so much even since I began this blog—I look forward to its continuing development. Thank you. See you on- and off-line.

References

Becker, H. S. (1991). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Carson, E.A. (2015). Prisoners in 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Bulletin.

Cooley, C.H. (1964). Human nature and the social order. New York: Schocken Books.

Dissanayake, E. (1992). Homoaestheticus: Where art comes from and why. New York: The Free Press.

Fox, W. M. (1997). The hidden weapon: Psychodynamics of forensic institutions. In D. Gussak & E. Virshup (Eds.), Drawing time: Art therapy in prisons and other correctional settings (pp. 43-55). Chicago, IL: Magnolia Street Publishers.

Howard, T.C. (2008). Who Really Cares? The Disenfranchisement of African American Males in PreK-12 Schools: A Critical Race Theory Perspective. Teachers College Record, 110 (5) 954-985.

James, W. (1890/1918).The principles of psychology. Vol.1 and Vol.2. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Kornfeld, P. (1997). Cellblock visions: Prison art in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mead, G.H. (1964). On social psychology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sagarin, E. (1975). Deviants and deviance: An introduction to the study of disvalued people and behavior. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Spector, M., and Kitsuse, J.I. (1973). Social problems: A re-formulation. Social Problems, 21 (3) 145-159.