Fantasies

What’s the Deal with “Furries?”

What a decade of research reveals about a misunderstood subculture.

Posted July 24, 2017 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

This contribution to Animals and Us was written by Dr. Courtney Plante, a social psychologist and co-founder of the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. This is an international team of social scientists studying the furry fandom. He is also the lead author of a compendium of findings from their studies of the furry fandom. (You can read the book FurScience! here.)

Furries. You might know them as “the people who dress up in the giant animal mascot costumes.” Or, depending on the media you consume, you may also know them as “the people who think they’re animals and have a weird fetish for fur.” Or, just as likely, you have never heard the term “furry” before outside the context of your pet dog or the neighbor with the back hair who mows his lawn without a shirt on every Saturday. Regardless of what you have or have not heard about furries, it might surprise you to learn that there is a team of researchers who have devoted their careers to studying this fandom. Perhaps even more surprising is what nearly a decade of research on the subject can tell us all about how we relate to animals, how we understand ourselves, and how we benefit from letting the inner child run wild every so often.

What are furries?

Before talking about what we can learn from furries, it would be useful to have an idea of what they are, exactly. Put simply, furries are fans. In the same way that Star Trek fans are fans of Star Trek and sports fans are fans of sports, furries are fans of media that features anthropomorphic animals—that is, animals who walk, talk, and do otherwise human things. At first glance, it seems like anthropomorphic animals are a bizarre thing to be a fan of. That is until you realize that most North Americans today grew up watching Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny cartoons and reading books like The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Charlotte’s Web, and continue this proud tradition by taking our children to see the films like Zootopia. Sure, the intended audience of these works may be children, but the same could also be said for Star Wars and Harry Potter, a fact that has not dissuaded the millions of adult fans of these series either.

Demographically, the furry fandom is comprised predominantly of white males in their teens to mid-twenties. For the most part, they represent what you would expect to find in a typical geek or nerd subculture: Above-average school performance (nearly half are college students), an interest in computers and science, and a passion for video games, science fiction, fantasy, and anime. Less typical, however, is the fandom’s LGBTQ demographics: Furries are seven times more likely than the general population to identify as transgender and about five times more likely to identify as non-heterosexual. Given this composition, it should come as no surprise that the furry fandom is a community defined in no small part by its inclusivity. This fandom embraces the norms of being welcoming and non-judgmental to all.

But aren’t furries…?

Misconceptions abound about furries, with media articles routinely mischaracterizing them as fetishists or as psychologically dysfunctional people. Many such misconceptions are demonstrably false, borne often out of a lack of clear understanding about what furries do as a group. For example, the misconception that furries are people who obtain sexual gratification from wearing mascot-style fursuits stems from a small percentage of furries, approximately 20 percent, who manifest their fanship through costuming. However, as with other fan communities (e.g., video game convention attendees, anime cosplayers, sports fans who wear their team’s jersey), such costuming is rarely done for the purpose of sexual gratification and is almost always done as a form of self-expression or performance. And, like other fandoms, one’s interest in furry can manifest in a variety of ways: drawing or commissioning furry-themed artwork and writing, playing furry-themed games, costuming and performing, and gathering with others who share the same interest.

Another such misconception stems from the mistaken belief that furries are not fans, but rather are people who believe themselves to be, in whole or in part, animals. In actuality, this definition better reflects a group known as Therians, whose sense of self includes non-human animals (e.g., the spirit of a wolf trapped in a human body). The vast majority of furries feel fully human and have no desire to become a non-human animal; they simply enjoy media that features animals who walk, talk, and do otherwise human things.

What can furries teach us about our own psychology?

Now that you have a better understanding of what furries are, and what they are not, it is worth asking what nearly a decade of research on this group can tell us about people in general. Three findings are of particular interest.

1. Furries are an excellent case study for the psychological principle of moral inclusion and how it relates to non-human animals. Put simply, when something is included within a person’s moral domain, it is subject to their moral principles. In contrast, things excluded from that moral domain are deemed beyond moral consideration. Practically speaking, those who fall within our in-group tend to also fall within our moral domain, while those belonging to out-groups are less likely to gain moral consideration. In the case of furries, who spend considerable time anthropomorphizing animals, this means that many non-human animals fall within the same moral domain as people do. As such, furries are more likely than non-furries to be opposed to the use of non-human animals for commercial or research purposes.

2. The vast majority of furries create a fursona—that is, a furry-themed avatar used to interact with other members of the fandom. Fursonas typically consist of one or more animal species, a name, and personality traits or other characteristics. Given the fantasy-themed nature of the furry fandom, individual furries are free to create representations of themselves unbounded by reality. As such, they can reconceptualize themselves with regard to age, gender, personality, or physical characteristics. Research has shown that most furries create fursonas representing similar, but idealized versions of themselves. Many furries report that, over time, their own self-concept tends to become more like that of their fursona. This may be due to the fact that, over time, others begin to interact with them as that idealized self, validating it and helping them to internalize it as part of themselves.

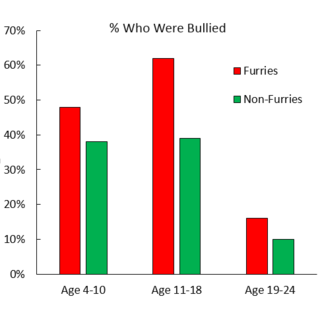

3. The furry world is one of fantasy, where dragons co-exist with bipedal, talking wolves and impossible hybrids. Because the world of furry content is so broad and all-inclusive, the fandom itself tends to reflect those norms. After all, if I am spending time playing pretend as a neon-blue cat that walks and talks, am I in any position to judge you for what you wear or how you choose to identify? To this end, many furries describe the fandom as one of the first places where they felt like they could belong, something that needs to be contextualized with the fact that furries are about 50 percent more likely than the average person to report having been bullied during childhood. For most furries, the fandom is about more than just indulging a child-like fantasy every once in a while. It is about forging lifelong friendships and building a social support network in a community who will not judge them for having unconventional interests. So while most of us would look at a person who watches cartoons or costumes as an anthropomorphic dog, wondering: “What’s wrong with that person?” The data suggest that these very same fantasy-themed activities are a fundamental part of that person’s psychological well-being.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing that a decade of research on furries can tell us is that, in the end, furries are no different than anyone else—they have the same need to belong, need to have a positive and distinct sense of self, and need for self-expression. Furries, in other words, are just like you—but with fake fur!

Click here for a list of publications on furries by the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Dr. Courtney Plante can be contacted at cplante@uwaterloo.ca.

* * * * *

References

Roberts, S. E., Plante, C. N., Gerbasi, K. C., & Reysen, S. R. (2015). Clinical interaction with anthropomorphic phenomenon: Notes for health professionals about interacting with clients who possess this unusual identity. Health and Social Work, 40(2), e42-e50.

Plante, C. N., Reysen, S. R., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2016). FurScience! A summary of five years of research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: FurScience.