Animal Behavior

Rethinking Rescue: Who Deserves the Love of a Dog?

Carol Mithers's new book unites the causes of animal welfare and social justice.

Updated August 21, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Mithers's book focuses on Lori Weise's decades working with people in poverty and the animals who love them.

- Mithers's most important concern is how human poverty and inequality affect the fate of animals.

- She also looks at contradictions within the no-kill/rescue movement, which are little-known outside it.

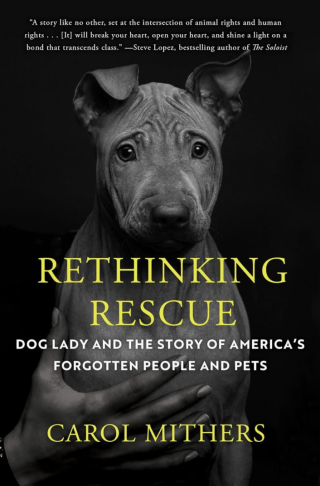

I’ve long been interested in the lives and fate of rescued dogs, the spirit of empathic kinship, and the relationships between rescued dogs and their humans, so when I learned about Carol Mithers’ new book, Rethinking Rescue: Dog Lady and the Story of America’s Forgotten People and Pets, I couldn’t wait to get my hands and eyes on it.1

I’m thrilled I did because my learning curve was vertical as I read about the seminal work of Lori Weise, known as the Dog Lady, who spent decades caring for people in poverty and the animals who love them. Carol “boldly confronts two of the biggest challenges of our time—poverty and homelessness—in asking the question: Who deserves the love of a pet?” I’m pleased she could answer a few questions about her riveting book.

Why did you write Rethinking Rescue?

When I met Lori Weise in 2012, I knew nothing about the humane world but was spellbound by her stories of working with unhoused dog owners in Downtown L.A. Then I witnessed her cutting-edge and very successful effort to keep dogs out of the shelter by helping their financially struggling owners. I knew there was a story there, and it came into focus when I realized that Lori had begun working around the same time that the no-kill/rescue movement took off. Her efforts both paralleled and countered that well-intentioned movement, revealing its flaws—in particular, the failure to include the poor and people of color.

How does your book relate to your background and general areas of interest?

I’ve always been interested in the stories of extraordinary women and the intersection of movements with the wider culture. (In my first book, I looked at the way a psychotherapy cult’s rise and fall reflected changes taking place in America.) Lori is brilliant, complex, and a person scarred by childhood experiences whose drive to help human-dog families gave her a path to re-empowerment. As I learned more about the no-kill/rescue movement, I realized that while it absorbed huge amounts of human time, money, and energy, no one had examined it as a political and cultural force.

Who do you hope to reach with your interesting and important book?

I want my book read by those concerned with animal welfare and those focused on social justice, who normally don’t realize that their issues overlap. Philip Alston, the United Nations special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, has said that “the distinctively American response to poverty in the 21st century” is punishment. We punish defendants who can’t make bail, addicts who can’t afford treatment, and the unhoused who sleep on the sidewalk. Law professor Dorothy E. Roberts wrote that it was parental poverty, not the type or level of maltreatment, that predicted whose children were put in foster care.

The same is true with pets: If an animal gets out and is picked up by animal control, an owner who can’t pay a redemption fee will lose the pet, which in turn can lose its life. If a dog or cat has an untreated wound or illness, an owner can be fined for failing to care for it.

The cost of veterinary care has escalated more than 60 percent in the last decade, so a low-wage worker’s options are to risk punishment, take on catastrophic levels of debt, or give the pet away. As Lori put it, “Imagine you were poor and had a sick child who would get care only if you agreed to give her to someone else.

What are some of the major topics you consider?

The most important is how human poverty and inequality affect the fate of animals. America’s jails are full of poor humans, and our shelters are populated by their pets. The no-kill/rescue movement, largely middle-class or better, has focused on saving shelter animals through adoption rather than trying to understand why they need saving.

The traditional rescue story portrays these animals as victims of “bad” humans whose lives will be improved if they’re moved to “better,” aka more affluent (and usually whiter) homes. This narrative allows the adopter of a “rescue” dog or cat to bask in their heroism while writing off the family that may have loved their pet before they did. Those facing the stressors and obstacles imposed by poverty as they struggle to care for a beloved animal get judged rather than helped.

The book also looks at contradictions within the no-kill/rescue movement, which are little-known outside it. They include racial bias and the sometimes shocking ways we offer needy animals more compassion than needy humans. After Hurricane Katrina, for instance, some dogs were transported out of New Orleans on air-conditioned buses even as people sweltered in the Astrodome.

I look at the way that stories of pet suffering can be manipulated by con artists, who use fake or exaggerated tales to gin up donations, and how municipal shelters’ need to keep their euthanasia rate low can enable animal hoarders. Too often, animal lovers give a pass to anyone with the title of “rescuer” and don’t ask very basic questions that would help them weed out the bad apples.

Finally, the book shows how someone with vision and humility can create real change. And that love for animals is a uniting force, one that transcends neighborhood, class, and race.

How does your book differ from others on these topics?

Most rescue-themed books tell a conventional story in which a suffering animal is saved and given a new life. But My Dog Always Eats First (Leslie Irvine), Underdogs (Arnold Arluke and Andrew Rowan), and The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals (Katja M. Guenther) also examine issues of pets, poverty, and inequality. None have a central character like Lori, and all three are written by academics and are somewhat academic in tone.

Are you hopeful that people will treat struggling pet owners with more respect, dignity, and compassion?

Yes! The dialogue begun by her work has already brought change. Groups both small and large (e.g., Maddie’s Fund, the ASPCA, and Best Friends) have acknowledged and apologized for past bias. Across the country, we’ve seen an increase in programs to serve both people and pets and efforts to help struggling owners keep their animals with them.

I hope this change lasts. Between COVID-era lack of access to affordable sterilization and economic stresses, shelters and rescue groups are overwhelmed with litters of puppies and kittens and surrendered pets. Adoption rates are down. More than ever, we need to see that there’s a difference between protecting animals and blaming humans without resources for failing to care for them.

References

In conversation with Carol Mithers, a journalist who has written about Los Angeles, women’s issues, and extraordinary women for over 30 years. Her work has appeared in The New York Times; Los Angeles Times; LA Weekly; O, the Oprah Magazine; Los Angeles Magazine; More; Town & Country; Architectural Digest; Ladies’ Home Journal; Parenting; The Bark; The Nation; California magazine; Buzz; Salon; The Daily Beast; and elsewhere. She is also the author of three books, including Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War, written with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Leymah Gbowee. Mighty was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and has been reprinted in 14 languages. Mithers lives in Los Angeles, where she has raised three demanding rescue dogs.

1) Some links to book-related stories: Pet Rent is the Newest Tool of Housing Discrimination; Most Americans Have Pets. Almost One Third Can’t Afford Their Vet Care; Los Angeles Renters Fight Back to Keep Their Pets – and Homes; When is a Rescuer a Hoarder?; For the Love of Old Dogs; A dog, a neighborhood, and a different way of seeing; Are We Loving Shelter Dogs to Death?

What Wild Rescued Animals Teach Us About Life and Love; Larry and Harry Are Rescued Dogs and No Quirkier Than Yours; My Dog Always Eats First: Homeless People and Their Animals; Underdogs: Treating Needy Pets in Disadvantaged Communities.