Animal Behavior

How Animals Reshaped Cultures on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Dr. Marcy Norton's new book about humans and animals after 1492 is a must read.

Posted February 27, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- When Indigenous people encountered the European practice of animal husbandry, they were disgusted.

- The idea of eating another being whom one had fed—the essence of livestock husbandry—was abhorrent.

- This book explores what cultural conditions foster or hinder our abilities to recognize animal subjectivity.

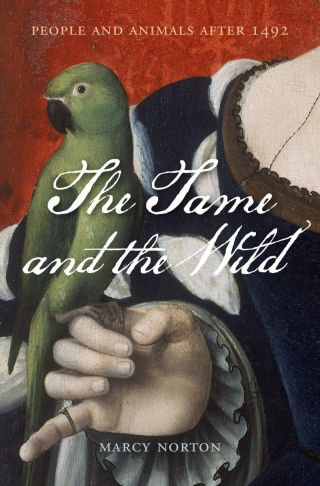

I'm very interested in human-animal relationships (anthrozoology) and always want to learn more about the history and roots of these sorts of relationships.1 That's the very reason I was so glad to learn of Dr. Marcy Norton's new book The Tame and the Wild: People and Animals After 1492 on the history of human-animal relationships, which places wildlife and livestock at the center of the story and shows how different views of animals reshaped people on both sides of the Atlantic. I'm thrilled Marcy could answer a few questions about her must-read revision of humans, animals, and cultural change.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write The Tame and the Wild?

Marcy Norton: I am baffled by this paradox: On the one hand, we know that animals suffer more than at any point in history. Consider the billions (!) of animals who suffer in confinement and then are slaughtered for human overconsumption, and the others who die because of climate change, water pollution, deforestation, etc. And, yet, on the other hand, so many of us have pets whom we adore, and there is an ever-growing appetite to learn about scientific research (such as your own!) demonstrating the amazing capacities of nonhuman animals. So, as a historian, I wanted to understand how we got here.

MB: What are some of the major topics you consider?

MN: My book challenges the idea that treating animals as livestock is a natural and normal way to interact with other creatures. A lot of people—scholars included—assume that animal domestication leading to livestock husbandry is a necessary stage of development for cultural progress. Instead, I show that across Indigenous America—I focus on Greater Amazonia (lowland South America and the Caribbean) and Mexico—humans developed very different kinds of relationships with other animals.

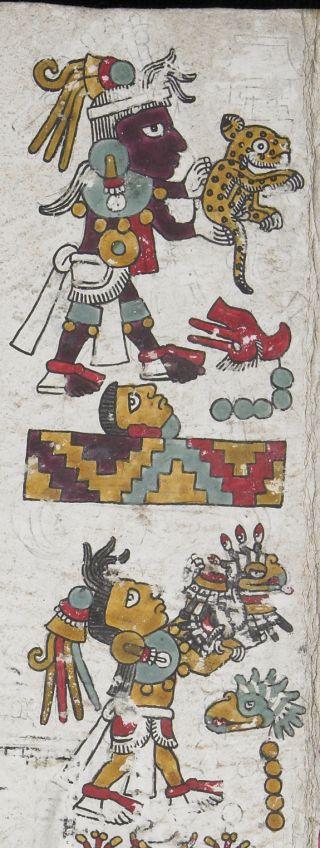

More specifically, I explore “familiarization”—a word that describes the process of taming wild animals from almost every imaginable kind of species: most commonly, parrots and monkeys, but also manatees, raccoons, capybara, coati, deer, iguana, rattlesnakes, jaguars, coyotes, tapir, peccaries, ducks, and many other types of birds. Hunters brought home the orphans of prey, or sometimes expressly captured young animals. They were then nurtured and tamed, usually by women, so that they became beloved kin. European travelers wrote admiringly of Indigenous people’s taming abilities and also marveled at the freedom possessed by familiarized animals; they noted that they would often wander or fly into the forest, and then come back at night. These animals did not have jobs like European hunting dogs or war horses,

MB: So are you saying they kept pets?

MN: While these tamed animals resemble our modern pets, they are not the same. First, unlike the vast majority of our pets, namely dogs and cats, these animals began their lives in the wild, not as domesticates. And, even more importantly, they belonged to species that in other contexts, were often hunted. Once the animals were fed—the paramount form of nurturing—eating them was off-limits. For this reason, when Indigenous people in Greater Amazonia initially encountered European-style animal husbandry, they were absolutely disgusted, but not because they were vegetarians or vegans. Rather, for them, to eat a being whom one had fed—the essence of livestock husbandry—was abhorrent. Though not pets, familiarized animals contributed to their emergence: Beginning in 1492, when Indigenous people in the Bahamas gifted Columbus tamed parrots, the influx of Native-tamed birds (such as the one on my book cover) led Europeans to think about human-animal relationships in new ways.

Native people in Mexico, too, practiced familiarization, both before and after the Spanish invasions. Unlike in Greater Amazonia, however, in Mexico, there were also domesticated animals—namely dogs and turkeys. But, in my book, I explore how this domestication did not lead to animal husbandry as it did in Europe. For instance, most meat was consumed by the elite; commoners were predominantly vegetarian, and so meat eating was much less routinized than in Europe. Another important difference relates to subjectivity. In the West, eating livestock was—and for many still is—palatable because animals such as pigs, cows, chickens, etc. are considered objects rather than subjects. Yet, in Mexico, people did not deny the subjectivity of dogs and turkeys whom they ate.

MB: Can you talk more about how you explore animal subjectivity?

MN: This question of animal subjectivity is another major theme of the book. Subjectivity—which I use interchangeably with personhood—is the term we use to describe the idea of an individual animal having emotional and analytic faculties, such as the capacity to reason or grieve, and distinctive desires and perspectives. The question of animal subjectivity has been mostly the domain of scientists (such as yourself!) who study animals in laboratories or in the wild. I approach the question differently: I ask what cultural conditions foster or hinder humans’ abilities to recognize the subjectivity of other animals?

In my view, animal husbandry is the root cause of Westerners viewing so-called livestock as objects. For instance, I found that the slaughterhouse (where laborers kill animals) as an institution separate from the butcher (where consumers buy meat) emerged much earlier than people realize, around 1500. By concealing the operation of killing animals, the slaughterhouse, along with other husbandry practices, enabled people to disconnect meat, hides, and other “products” from living, feeling, thinking animals.

Perhaps more surprisingly, I found that hunting on both sides of the Atlantic required hunters to recognize the subjectivity of nonhuman animals. In Europe, this was particularly the case with the dogs, horses, and raptors—their vassals—with whom hunters collaborated when pursuing wild prey. In Greater Amazonia and Mexico, hunters did not work with vassal animals. Instead, their hunting operations centered around intense imitation (or mimesis), and that, along with prolonged observation, gave them profound understanding and respect for the capacities of their prey.

MB: Are you hopeful that as people learn more about the history of human-animal relationships they will treat other animals with more respect and decency?

MN: Yes, I am! People often think that it is more natural and traditional to treat animals as food-in-waiting than to cherish them as companions. But when we gaze beyond a Eurocentric horizon, we see that historically it is just as “normal” for humans to recognize the subjectivity of all animals and to perhaps internalize the Amazonian perspective that we should not kill whom we feed.

References

In conversation with Dr. Marcy Norton, associate professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of the award-winning Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World. Her research has been supported by the Guggenheim Foundation, the Library of Congress, and the Max Planck Institute.

1. For more discussion of the history of human-animal relationships, see Beastly: The Entangled History of Animals and Us; A Historical Perspective on Studies of Animal Emotions; Hats: The Deadly History of Who We Put on Our Heads; Which Animal Has Most Changed the Course of History?; and As Food Animals Became "Things," Their Feelings Were Ignored.