Animal Behavior

How Animals Talk: A Remarkably Insightful and Prescient Book

Published in 1919, William Long's book shows the importance of natural history.

Posted November 5, 2018

"The scientist does not study nature because it is useful, he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing, and if nature were not worth knowing, life would not be worth living." (Jules Henri Poincaré)

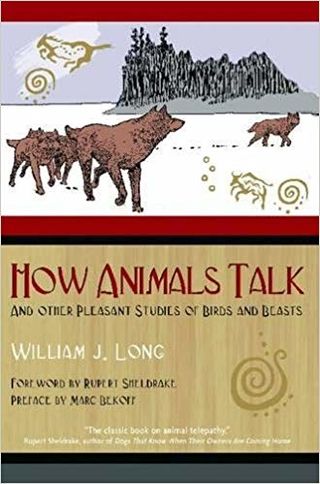

How Animals Talk, originally published in 1919, is a most stimulating, inspirational, and prescient book. Its subtitle, And Other Pleasant Studies of Birds and Beasts, is indicative of William J. Long's sheer and unbridled delight in observing and learning about the mysterious ways of the nonhuman animal beings (animals) with whom we share the earth. A curious naturalist at heart, Long shows how curiosity, patient observation, and detailed descriptions can help us understand and appreciate animals, vertebrates and invertebrates alike, from wolves to insects, deer to ducks. Long also emphasizes how important it is to know about the natural history of different species and how deficient armchair speculations about animal behavior really are. The value of long-term detailed observations can't be emphasized too strongly. Far too many people—then and now—who write about animal behavior, haven't actually carefully observed or studied animals or even shared their homes with them. Long live natural history, a supposedly "soft science" that is often dismissed by people who remain in the ivory tower of their armchairs and don't take the time to get out to observe and study animals where they live.

In How Animals Talk, Long presages numerous areas that currently are "hot topics" in the study of animal behavior and presents a staggering array of animals. He discusses chumfo, the super-sense, a word for which he is indebted to an African tribe living near Lake Mweru. Long notes, "According to these natives, every natural animal, man included, has the physical gifts of touch, sight, hearing, taste, smell, and chumfo . . . This chumfo is not a sixth or extra sense, as we assume, but rather the unity or perfect coordination of the five senses at their highest point." So, often, when we are amazed at the sensory abilities of many animals and how in touch they are with their surroundings it is because they "are there," they are totally present and are able to integrate information across the different senses. This discussion presages the field called sensory ecology.

Long also points in the direction of behavioral phenomena that still need detailed study, such as animal telepathy. He recognizes that there is no proof of animal telepathy but that it is a working hypothesis that deserves close attention. He finds that “wild birds and beasts all exercise a measure of that mysterious telepathic power which reappears now and then in some sensitive man or woman." And in his chapter "On Keeping Still," Long writes about the "feeling of being watched" that he says "may be too intangible for experiment, or even definition."

Long's knowledge of animal behavior is astounding, even by today's standards. And that is among the reasons why his book deserves to be rediscovered by a broad audience in a world in which more and more people are craving to learn as much as they can about our animal kin. Our old brains, still very much paleolithic-like, draw us back to nature as magnets attract iron to their surfaces. In the absence of animals we are alone in a silent world, torn apart from other beings who help define who we are in the grand scheme of things.

Long also isn't afraid of recognizing the importance of what I call the notorious "A" words—"Anecdote" and "Anthropomorphism." Stories underlie all sorts of research, from physics to philosophy, biology to sociology, anthropology to theology. The same is so for studies of animal behavior. For example, he describes the wonderful color plate showing a family of red foxes with the caption “The old vixen lies apart where she can overlook the play and the neighborhood.” As he marvels at the silent communication that occurs between the mother fox and her young he says, “If a human mother could exercise such silent, perfect discipline, or leave the house with the certainty that four or five lively youngsters would keep out of danger or mischief as completely as young fox cubs keep out of it, raising children might more resemble ‘one grand sweet song’ than it does at present.”

The plural of anecdote is data and there is no adequate substitute for being anthropomorphic; we can only communicate about animals with the language we use in all other aspects of our daily lives. A quotation from another of Long’s wonderful books, Brier-Patch Philosophy by Peter Rabbit published in 1906, eloquently captures his views on anthropomorphism: "It is possible, therefore, that your simple man who lives close to nature and speaks in enduring human terms, is nearer to the truth of animal life than is your psychologist, who lives in a library and to-day speaks a language that is to-morrow forgotten."

The careful use of anthropomorphism, in which we always take into account the animal's point of view, can only make the study of animal behavior more rigorous, interesting, and challenging. As human beings trying to learn as much as we can about animals we have to use the words with which we're most familiar to talk about our observations of animal behavior and to convey our knowledge. Claims that anthropomorphism has no place in science or that anthropomorphic predictions and explanations are less accurate than more mechanistic or reductionistic "scientific" explanations are not supported by any data. This is an empirical matter and before someone posits that anthropomorphism is a bad habit, he or she needs to show that it is not as good as other sorts of explanations. We really don't get any information at all about context, social or otherwise, if we describe grief or joy, for example, as a series of neuromuscular firings, as different types of brain activity, or as neurochemical reactions. All in all, anthropomorphism is a great aid in making sense of animal behavior and is alive and well as it should be. But, let me stress again that it must be used with care and we must always attempt to take into account each animal's point of view.

In How Animals Talk Long also delves into animal communication, cognition, emotions, and telepathy. He isn't afraid to cover topics that some scientists would call "taboo," and it is refreshing to discover that he knew an incredible amount about a vast number of different patterns of animal behavior, including some that do not lend themselves to hard-and-fast unambiguous explanations or, for that matter, easy data collection. The title of this book itself shows that Long knew that animals talked to one another, and it's hard to believe that some of my colleagues today wonder if this is so!

Long also knew that many animals experience rich and deep emotional lives and have a sense of morality (what I call "wild justice"). This is an area of research in which I've been keenly interested in for decades. In my opinion, it's not a question of if emotions have evolved but rather why they have evolved. Surely, a whimpering or playing dog, or a chimpanzee in a tiny cage or grieving the loss of a friend, or a baby pig having her tail cut off —"docked" as this horrific and inexcusable procedure is called — or having her teeth ground down on a grindstone, feel something. And surely, animals don't like being shocked, cut up, starved, chained, stunned, crammed into prison-like cages, tied up, isolated, or ripped away from their families and friends.

Long knew, as we do, that animals aren't unfeeling objects. If they were, I'm sure he wouldn't have found animals to be so fascinating. Scientific data, what I call "science sense," along with common sense, compassion, and heart, are all needed to learn more about animal passions and how animals feel about the innumerable situations in which they find themselves. Emotions function as social glue and social catalysts. Animal emotions and mood swings grab us, and it's highly likely that many animals exclaim "Wow!" or "My goodness, what is happening?" as they go through their days enjoying some activities and also experiencing pain and suffering at the hands of humans.

In How Animals Talk readers will discover lengthy descriptive discussions of play, aggression, territoriality, homing, communication, mating, social organization (called the herd phenomena and the swarming instinct), and caregiving behavior in a wide variety of species. Long clearly knew about what is now called the "human dimension," the human or anthropogenic effects on the behavior of animals stemming from our incessant intrusions and trespasses into their lives. He notes that we have changed the behavior of many wild animals, for example, their fear responses to our presence and their subsequent use of space. Many individuals of different species change their daily activities and travel patterns when humans are present. We always need to remember and to know about the ubiquitous consequences of our presence. We truly are here, there, and everywhere.

Concerning my own interests in how studies of animal behavior, especially animal emotions and sentience, can influence our understanding of them and how we treat them, Long's book, though written decades ago, lays the foundation for a change in how we should use and abuse them in factory farms, in circuses and rodeos, and in education and research. As we change the paradigm and move forward we're in a good position to use as a guide what has come to be called the "precautionary principle." Basically, this principle maintains that a lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as an excuse to delay taking action on some issue. In the arena of animal emotions and animal sentience, I have argued that we do know enough to make informed decisions about animal emotions and animal sentience and why they matter. And even if we might be "wrong" some of the time this does not mean we’re wrong all of the time. At least we won’t be adding more cruelty to an already cruel world, by granting that animals are emotional, sentient beings and accordingly treating them with respect. When in doubt we should err on the side of the individual animal. I'm sure Long would agree with these sentiments.

It's also okay for researchers to be sentimental and to go from their heart. We need more compassion and love in science, more heartfelt and heartful science. Simply put, we must "mind" animals and redecorate nature very carefully. We must blend together scientific science sense with common sense, compassion, and heart in our efforts to provide the best treatment for all animals all of the time.

Perhaps if enough people read this book there will be a change in how we move on from here. Reducing animals to mere numbers or objects, and sanitizing descriptions of their behavior and emotional lives with cold, terse, and third-person prose ("the researcher watched the subject") rather than first-person prose, objectifies animals and distances "us" from "them." This dualism must be resisted vigorously. We are not the only animals who are rational, conscious, self-cognizant, able to manufacture and use tools, display culture, draw and paint, reflect on the past and make plans for the future, or communicate using a sophisticated set of rules that resemble what we call language. Perhaps we’re the only species that cooks its food, but because there are so many startling things that remain to be studied, maybe we're not. I found myself making an ever-growing mental list of things that I didn't know as I read Long's book, and I've been studying animal behavior for a long time. That's how innovative this book really is.

When I try to imagine what Long was feeling when he wrote How Animals Talk, I smile and can feel his unbounded delight and awe at the magnificence of so many different animals. His careful fieldwork presages that of many ethologists who followed, including the three winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973: Nikolaas Tinbergen (often called the "curious naturalist"), Konrad Lorenz, and Karl von Frisch, who won this most prestigious prize for their discoveries concerning animal behavior.

I would love to have been William Long's student! And, in reading through Long's book I have indeed become his student. I admire Long's dedication to learning as much as he could about animals and for being so open about all that we don't know. Throughout How Animals Talk I was reminded of a wonderful quotation offered by Jules Henri Poincaré: "The scientist does not study nature because it is useful, he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing, and if nature were not worth knowing, life would not be worth living."

I only wish that Long could know that he has been rediscovered and so appreciated almost a century after How Animals Talk first appeared. So, I encourage you to find the book and enjoy the journey that Long lays out for all interested parties. Reading Long's book is a most pleasurable adventure into the heads and hearts of diverse groups of nonhuman animal beings. It would be perfect reading for a wide variety of classes on animal behavior and also for interested non-students and non-researchers. I find myself constantly going back to Long's wonderful book and gushing with the joy of reading his detailed descriptions of the lives of the fascinating animals with whom we share out magnificent planet.