Gender

Women May Benefit from "Gender Blindness" in the Workplace

Gender parity in the workplace requires organizational change.

Posted May 17, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Gender blindness, or downplaying gender differences, is one strategy for achieving equality in the workplace.

- It promotes self-confidence and agency in women, leading to more assertiveness, risk-taking, and negotiating.

- Gender equity in the workplace also requires promoting equal opportunities and equal treatment of women.

- Both individual characteristics and situational influences determine how men and women act in the workplace.

Research by Ashley Martin, Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and Katherine Phillips, formerly Professor at the Columbia University Business School, found that women who downplayed the differences between men and women, i.e., gender blindness, felt greater power and confidence than women who celebrated women’s distinctive qualities, i.e., gender awareness.1 The confidence that came from adopting a gender blindness strategy in male-dominated work situations led the women in the studies to:

- Think they could overcome challenges at work.

- Feel comfortable disagreeing with others.

- Become more willing to take risks, take initiative, and negotiate.

An alternative strategy to achieve gender parity in the workplace is gender awareness, which says that promoting and embracing gender differences will lead to men and women interacting more cooperatively. This, in turn, would ideally contribute to a more cooperative and efficient workplace.2

What Is Gender Blindness?

Gender blindness as Martin and Phillips define it is a strategy for achieving equality in the workplace.3 This strategy removes the “male” connotation from traits and behaviors like assertiveness, competitiveness, and risk-taking, which are necessary to get ahead in the workplace. These researchers note that “degendering” these characteristics helps women recognize such characteristics in themselves, resulting in them feeling more confident.

How the Gender Blindness Strategy Works

Martin and Phillips theorized that a strategy of gender blindness would benefit women in typically male-dominated workplaces by increasing their confidence in themselves.4 Previous research has shown a gap in confidence in the workplace between men and women, with men showing greater confidence, which is important in overall career success. This confidence gap shows up in salary negotiation, self-promotion, and performance, which are precursors to success in managerial positions.

These researchers also wanted to demonstrate that having more confidence would encourage women to be more active in the workplace.5 Historically, men and women have been assigned different social roles, with men taking on agentic roles like working or hunting while women took on communal tasks like child-rearing. Thus, men are seen as agentic—assertive and competitive—while women are seen as warm and kind.

Across five studies testing this model, Martin and Phillips found that gender blindness was related to and increased women’s confidence.6 Gender blindness was also related to and increased women’s sense of agency. These findings were particularly true in the workplace.

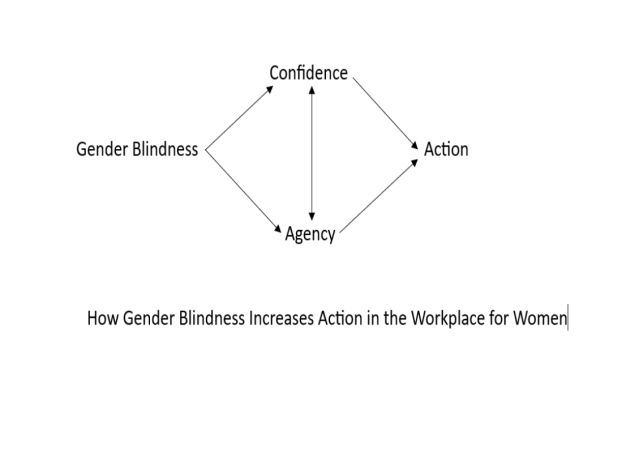

Gender blindness across these studies affected taking action in a two-step process. The schematic below shows that gender blindness in the workplace can increase women’s self-confidence and identification with agentic traits, which supports workplace assertiveness, risk-taking, and negotiating.

Gender Parity in the Workplace Also Requires Equal Opportunities and Treatment of Women

There is a long-standing debate in psychology about what factors determine how we act in various situations.7 Personality psychologists argue that our characteristics, like assertiveness, will determine our behavior in the workplace, for example. Other psychologists, “situationists,” propose that our circumstances, e.g., how we are treated, will determine how we act in the workplace.

After many years of debate, psychologists have agreed that specific behaviors are driven by the interaction between factors in situations and the individual tendencies that a person brings to these situations.

So, even as women gain confidence in the workplace, they must be given equal opportunities and treatment by supervisors. Catherine H. Tinsley, Professor of Business Administration at Northwestern University, and Robin J. Ely, economist and Professor of Business Administration at Harvard University, report multiple studies that show women are treated differently than their male counterparts.8

- They are less embedded in networks that offer opportunities to gather vital information and lack access to useful contacts, which impairs their ability to negotiate successfully in the workplace.

- They are less aware of opportunities for good assignments and promotions. When women fail to “lean in” on such opportunities, they may be viewed as lacking confidence.

- Women are under greater scrutiny in the workplace than men, resulting in their mistakes and failures being scrutinized more carefully and punished more severely. Such treatment makes it more likely women will not speak up in meetings, thus being perceived as less assertive and action-oriented.

- Women get less frequent and lower-quality feedback than men. The lack of good feedback affects women’s sense of worth, causing them to be less effective negotiators.

Tinsley and Ely tell us that If we want gender parity in the workplace, we cannot just “fix” women.9 Women need a context that maximizes their chance to succeed. They suggest four steps managers can take to create the conditions necessary for women to succeed.7

- Question the narrative: Managers must not accept traditional narratives that women are not competitive, i.e., that they lack “fire in the belly.”

- Look for alternative explanations for lack of performance: For example, how much hands-on training are women receiving compared to men?

- Change the work context: One manager who did not think a female employee was assertive enough invited her to join the team and made a conscious effort to treat her exactly as he would treat someone he deemed a superstar. He introduced her to the relevant players in the industry, told others involved she was a leader on the team, and gave her enough feedback and coaching to perform at a high level.

- Promote continual learning: Have regular meetings in which managers challenge assumptions and change work conditions to provide an equal context for the women and men who work for them.

We Need Both Gender Blindness and Equal Opportunities in the Workplace

Over the last decade, efforts have been made to promote gender equality in typically male-dominated public and private workplaces.10 Gender blindness is one of the major approaches to achieving gender equality. However, this approach runs the risk of trying to “fix women.” Relying too heavily on “fixing women” ignores what psychologists tell us—we must pay attention to how women and men are treated in their workplaces. Fortunately, researchers like Tinsley and Ely have helped us analyze how organizations treat women differently than men, often based on old ideas about women in the workplace. In the 21st century, we can adopt individual approaches like gender blindness along with challenging how men and women are treated differently on the job.

References

1. Martin, A.E. and K.W. Phillips. (2017) “What ‘blindness’ to gender differences helps women see and do: Implications for confidence, agency, and action in male-dominated environments.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 142, 28-44.

2. Martin and Phillips

3. Martin and Phillips

4. Martin and Phillips

5. Torres, N. “Women Benefit When They Downplay Gender.” Harvard Business Review. July-August 2018.

6. Martin and Phillips

7. Votaw, K. “The Person-Situation Debate and Alternatives to the Trait Perspective.” LibreTexts: Social sciences.

8. Tinsley, C.H. and R.J. Ely. “What Most People Get Wrong About Men and Women.” Harvard Business Review. May-June 2018.

9. Tinsley and Ely.

10. Kojok, Z.El. “Gender Blindness: Pros, Cons and Relation to Language. The Phoenix Daily. January 18, 2022.