Goldwater Rule

The Goldwater Rule is a statement of ethics first issued by the American Psychiatric Association in 1973 restraining psychiatrists from speculating about the mental state of public figures. The rule enjoins psychiatrists from professionally diagnosing someone they have not personally evaluated. The APA’s Ethics Committee affirmed and even expanded the rule beyond diagnosis to cover almost all psychiatric opinion in 2017, amid widespread public discussion of the mental health of President Donald J. Trump. The rule has also been affirmed by the American Psychological Association.

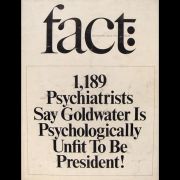

It is called the Goldwater Rule because it arose from events that occurred during the presidential campaign of 1964, when Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, a conservative Republican, was running against incumbent President Lyndon Johnson. Now-defunct Fact magazine solicited and published psychiatric opinions about Goldwater for partisan purposes. The incident proved deeply embarrassing to the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and for the position of psychiatry as a medical science.

During the 1964 presidential campaign, Fact magazine published a survey of psychiatrists who were explicitly asked whether Goldwater was psychologically fit to be president. The cover trumpeted “1,189 Psychiatrists Say Goldwater Is Psychologically Unfit to Be President.” What the cover didn’t say was that 12,356 psychiatrists were queried, only 2,417 responded. The vast majority of the responses were unsigned; 1,189 said no, 657 said yes, and 571 said they didn’t know enough about the matter to have an opinion. Both the APA and the American Medical Association warned Fact against publishing the responses of physicians who had never examined the candidate.

The published responses filled 41 pages of a special issue called “The Unconscious of a Conservative” and were further promoted in full-page advertisements in The New York Times and other newspapers. They included such statements as “I believe Goldwater has the same pathological make-up as Hitler, Castro, Stalin and other known schizophrenic leaders,” and “It is my feeling that Senator Goldwater appeals to the unconscious sadism and hostility in the average human being.”

Others said, “he is a mass murderer at heart,” and “it is apparent that Goldwater hates and fears his wife.” After losing the election by what is considered a landslide, the senator sued for libel and won in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. The award for damages was sufficient to put the magazine out of business.

At the time of publication, the APA deemed the article “yellow journalism” and publicly declared professional embarrassment. It said, “By attaching the stigma of extreme political partisanship to the psychiatric profession as a whole in the heated climate of the current political campaign, Fact has in effect administered a low blow to all who would advance the treatment and care of the mentally ill of America.”

Donald Trump’s displays of temperament, decision-making, and behavior so consistently violated presidential norms that questions of his mental health were raised by citizens, journalists, and public officials even before he took the oath of office. Barely three months into his tenure, in April 2017, 28 members of Congress introduced a bill seeking to prepare the 25th Amendment for possible use; it would allow for the formal determination of the president’s mental fitness to govern by a nonpartisan panel. (The 25th Amendment establishes procedures for the transfer of power in case of presidential incapacity; section 4 is specifically concerned with mental impairment.)

Public discussion of diagnosable conditions that could be affecting the president continued to occur—with or without mental health experts. Many psychiatrists and psychologists chose or were asked to offer informed opinion to a confused and concerned public. Others chose to criticize colleagues for violating the Goldwater Rule. Nevertheless, consensus arose that the president displayed, at a minimum, narcissistic personality disorder. References to President Trump’s narcissism have become commonplace and widely accepted—despite the Goldwater Rule.

It can be said that the Goldwater Rule served its original purpose in keeping mental health experts from making unverifiable and contradictory inferences about the mental health of public figures. But the cost of the rule appears to be increasingly high. There is growing awareness that it violates First Amendment rights of free speech, and a court test may be mounted on those grounds sooner or later. Equally important, the Goldwater Rule restricts those who know most about mental health from contributing to public discussion about political candidates and others, at a time when the mental fitness of leaders has become more important than ever. The Goldwater Rule may have once served the needs of a profession, but it does not serve the broader needs of the public.