Empathy

Jump the Empathy Wall

How we can surmount the barriers to empathy in our lives.

Posted January 5, 2019

Art and literature are powerful teachers if we open ourselves to listen to and see what they have to say. In reviewing the books I have read and the art I have seen during 2018, there is one book and one piece of art—that combined into one creation—have had the greatest impact. The theme and lessons are quite timely given our current U.S. political climate. Walls and empathy. How can we grow the latter and tear down, or jump over, the former?

It seems the answer has to do with an alchemy of open-heartedness, willingness to reach across divides, courage, creativity, curiosity (the good, not prurient kind), and humor (the good, not the dark and destructive kind). And a good pair of shoes to wear in order to do this sort of essential and hard work.

First, the book and a few stunning quotes. One of the most powerful books I read this year was literally placed into my hands by nurse and bookseller extraordinaire, Karen Maeda Allman of the Seattle indie bookstore extraordinaire, Elliott Bay Book Company. Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (The New Press, 2016), a disturbing yet oddly hopeful book, introduced me to the term empathy wall. In her words:

“An empathy wall is an obstacle to deep understanding of another person, one that can make us feel indifferent or even hostile to those who hold different beliefs or whose childhood is rooted in different circumstances. In a period of political tumult, we grasp for quick certainties. We shoehorn new information into ways we already think.…But is it possible, without changing our beliefs, to know others from the inside, to see reality through their eyes, to understand the links between life, feeling, and politics; that is, to cross the empathy wall?” (p. 5)

With an obvious love of language and precision, Hochschild writes:

“The English language doesn’t give us many words to describe the feeling of reaching out to someone from another world, and of having that interest welcomed. Something of its own kind, mutual, is created. What a gift. Gratitude, awe, appreciation; for me, all these words apply and I don’t know which one to use. But I think we need a special word, and should hold a place of honor for it, so as to restore what might be a missing key on the English-speaking world’s cultural piano. Our polarization, and the increasing reality that we simply don’t know each other, makes it too easy to settle for dislike and contempt.” (p. xiv)

That I left this book sitting on the nightstand beside my bed at home in Seattle—unread—for many, many months (the paperback version has an ominous, off-putting cover), and that I finally read it after returning from a four-month stretch of living and working in a foreign (to me) country (Scotland), is partly why I found reading the book a profound experience. The disorientation of reverse culture shock with its own unique opportunity to explore ways across that empathy wall back into my own culture—with a changed perspective on it—was an excellent time to read about “strangers in their own land.” I can relate to that feeling. (Wait, we have this much visible abject poverty and homelessness in this city and land of plenty with its over-the-top tacky consumerist Christmas? Just one of the questions continuously running through my head since returning home.)

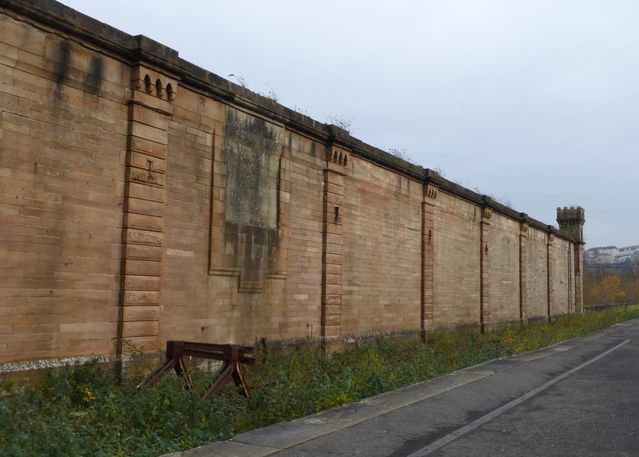

This is where the art comes in, providing a visual and different take on the empathy wall. In London, at the Tate Modern Museum, I came across the work of the Argentinian artist Judi Werthein. In 2005, she designed and produced a sneaker, called Brinco (“jump” in Spanish), that she distributed free of charge to migrants crossing the Mexico/U.S. border. The sneakers held a flashlight, a compass, pockets to hide money, and a removable insole with a map of the border area around Tijuana to Mexacali. At the same time, across the border in the U.S., she sold the same sneakers as “limited edition art objects” for $200 and donated the money to a Tijuana shelter for migrants.

The Tate exhibition of Werthein’s work was so effective because it included videotaped and written media coverage of this controversial “art activism” project, along with threatening letters she received from various people in the U.S. I lingered in this exhibition space long enough to observe a variety of reactions from museum visitors, including—of course—British supporters of Brexit.

We all have a deeply ingrained fear of the “other” that was originally likely intended to protect us—yet, if given unfettered license to expand and go unexamined, severely stunts our humanity. In the words of Parker Palmer in his book (another great book I read recently), Healing the Heart of Democracy: The Courage to Create a Politics Worthy of the Human Spirit (Jossey-Bass, 2011):

“…manipulating our ancient fear of ‘otherness’ is a time-tested method to gain power and get wealthy, if you have a public megaphone. Well-known media personalities—and too many political candidates and officeholders—exploit a market that will yield returns as long as fear haunts the human heart, a profitable enterprise in relation to their own financial or political fortunes but one that can bankrupt the commonwealth.” (p 58)

My hope for 2019 is that we can individually and collectively climb—or jump—the empathy walls that surround us.