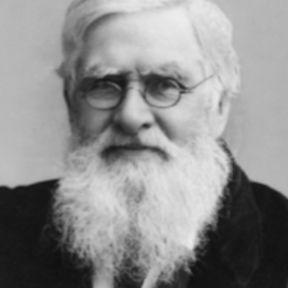

Herbert S. Terrace Ph.D.

Herbert S. Terrace obtained his Ph.D. at Harvard University in 1961, where he studied with B. F. Skinner. Since then he has taught at Columbia University in the Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry. He has conducted research on comparative research on pigeons, monkeys, and chimpanzees. Terrace has made important contributions in operant conditioning, ape language, animal cognition, and the evolution of language.

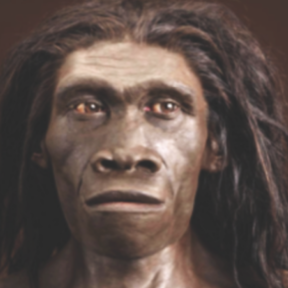

Following the lead of other behaviorists who attempted to teach chimpanzees, man's closest living relative, some rudiments of language, Terrace acquired an infant chimpanzee, Nim Chimpsky, and trained him to learn American Sign Language (ASL). Sign language was used because of the physical limitations of a chimpanzee's vocal apparatus. Nim’s vocabulary grew steadily and he began to combine signs. However, analyses of videotapes showed that most of Nim’s signs were cued by his teachers’ prompts.

Terrace concluded that the only reason Nim (and other chimpanzees) signed was to obtain rewards. Were it not for the teacher, Nim would try to grab a reward directly. When that failed, Nim learned that he had to sign to obtain the reward. Anticipating Nim’s signing, the teacher inadvertently made one or more appropriate signs, about a quarter of a second before he signed. Terrace also showed that prompting explained the signing of other chimpanzees who were trained to use ASL.

Because Nim only signed to obtain rewards, his signing was limited to the imperative function of words. That differs fundamentally from its declarative function, which is to name objects conversationally. Imperatives are a minuscule portion of human vocabulary. If human communication were limited to imperatives, language would have never evolved.

Initially, Terrace hoped that combinations of a chimpanzee’s signs would provide evidence that it could create a sentence. What Project Nim showed, however, is that a chimpanzee can’t even use signs declaratively. He therefore concluded that it’s pointless to ask if a chimpanzee can create a sentence.

In 1985, Terrace created a primate cognition laboratory in which he studied how monkeys learn to respond in the correct order to ascending and descending series of numerically defined stimuli, serial expertise (the ability of a monkey to become progressively better at learning arbitrary sequences, imitation of sequential performance and task switching).

Terrace also studied the metacognitive ability of monkeys. In humans, metacognition is assessed by asking subjects how certain they are about their knowledge of a particular topic. To assess metacognition in monkeys, Terrace devised a task in which the monkeys had the place a “bet” that was commensurate with their confidence in the accuracy of a response on a cognitive task (Kornell, Son & Terrace, 2007). Following each response, monkeys learned to select a “high confidence” symbol if their response was correct and a low “low confidence” symbol after an error. They did so even when the appearance of the confidence symbols was delayed for as long as 5 seconds after a trial.