Education

A Language Learning Tool Hiding in Plain Sight

Using video to simulate an immersive foreign-language learning experience.

Posted July 24, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

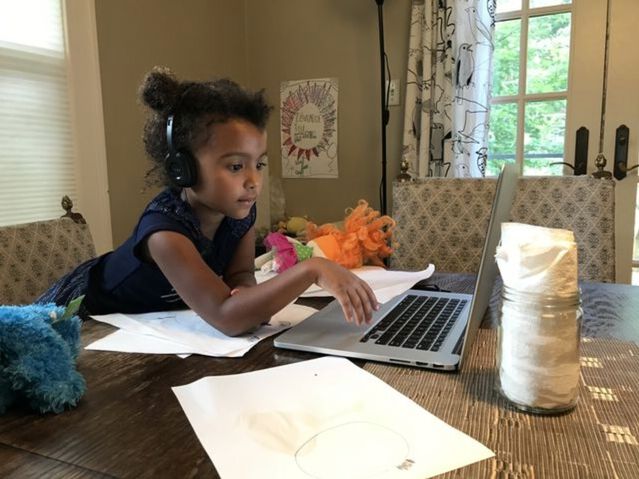

With summer activities canceled and social distancing the order of the day, kids are probably getting more screen time than most parents find reasonable. Since school reopenings will be delayed in many parts of the world, this state of affairs is likely to continue for a while.

Looking for a silver lining, one wonders whether there is any potential upside to this situation. It turns out that when it comes to passive screen time for non-educational programs, the answer depends on the language.

Research over the decades has found that exposure to educational programming contributes to children's cognitive development and that there are virtually no benefits to watching a run-of-the-mill video in one’s native language. In contrast, passive foreign-language video exposure, especially with native-language subtitles, is an effective way to acquire language skills. Vanderplank (2010) reviewed the extensive literature on the use of video for language learning and found that both children and adults can learn elements of second languages simply from viewing. Earlier Koolstra (1999) had shown that Dutch children acquired English vocabulary by watching English-language videos.

Learning occurred even without subtitles, but kids made the largest gains when subtitles were present. Uchikoshi (2006) found that watching TV at home improved the English-language skills of bilingual Latino children in the U.S. but watching in the classroom did not. Second-language video may not be as effective as conversing with a native speaker, but it is a productive route for language acquisition.

These findings will be familiar to any English speaker who has traveled widely and talked to people about how they learned the language. Native speakers of other languages who have spent large amounts of time with American video will be able to personally vouch for their veracity. Tens of millions of people across the world have learned the bulk of their English, and, for good or for ill, substantial amounts of what they know about Americans and American culture from American TV. What’s different now is that English is no longer the only game in town. Anyone with the internet can expose themselves to an enormous array of languages.

This literature, and real-world experience, is consistent with events in my household. I will recount the first half of this natural experiment here—a period of mostly passive screen time up until COVID hit, roughly March—and the second, after active online instruction began, in a later post.

We have a very liberal policy on screen time: there are no set limits. My three kids (ages five, five, and two) can watch as many videos as they like so long as they are in a foreign language. I have observed them watching French, Russian, Spanish, German, Bulgarian, Korean, Hindi, Portuguese, and Mandarin. (Because of diminishing returns, they must switch to a new language on the rare occasions on which they have watched more than two hours a day in any one.) The activity is not always purely passive. My Spanish and German aren’t good enough anymore to converse easily, but while we watch Spanish or German movies, I sometimes quiz them about the meanings of phrases, keeping it up until they rebel, usually after a few minutes.

I speak French moderately well and try to speak to them in French as much as I can, using Google Translate when I need a word or phrase. Up until schools closed, each child also took a 45-minute lesson once a week from a native speaker. We often read French books before bedtime but have only visited France once, for a week three years ago, and have visited no other French-speaking regions, nor have we been around a community of native speakers.

Thus, aside from my middling efforts and the infrequent classes, their direct human exposure to French was limited. Nevertheless, by March, my kids were as comfortable watching videos in French as English.

The practical effects of this approach became clear last summer, when my oldest daughter, then four, spent a few weeks in Bulgaria visiting my wife’s family. She had gone there each of the previous three years. Over that time her Bulgarian had improved, due in large measure to the six months her grandmother spends with us each year and her habit of conversing with Charlotte regularly in her native tongue. At the time, my daughter understood a lot of what was said but spoke only in single words and simple sentences in Bulgarian. During her last trip, she met a girl about her age at a restaurant. The girl didn’t speak English and with Charlotte’s limited Bulgarian they struggled to communicate. At some point, trying to express herself, the girl uttered a few words of French. Recognizing the language, Charlotte immediately switched to French and the two chatted away happily for an hour.

Even at that time, Charlotte’s French accent was almost native quality and her understanding excellent. With little formal instruction, she could speak in moderately complex sentences and possessed a substantial and growing vocabulary. From time to time she corrected my word choice and pronunciation and gave me French translations of English words when I asked.

The difference-makers were Netflix and YouTube. If her conversations with me, the books and her lessons were the sum total of her French experience, she might have been able to say one- or two-word sentences and understand simple language, but her speech and comprehension would not have been anywhere near as good as they were, and her accent would definitely not have been nearly perfect.

There are always tradeoffs. Each hour spent in front of a screen is an hour not spent playing, talking to someone face-to-face, or exploring the world. However, recognizing the benefits of certain video content, the American Academy of Pediatrics lifted its recommendation that kids be limited to two hours of screen time a day.

Research and my family’s experience support that decision. Our ability to learn language decreases with age after youth. Immersive environments in which people hear, speak, read, and write the language they are acquiring, are most efficient and effective for acquiring linguistic abilities. In the absence of such opportunities, exposing children to extended time with foreign-language video is a fruitful way to build linguistic capacity. If we avoid second-language screen time at this age, the opportunity for many children to acquire sophisticated foreign-language skills may be lost.

References

Robert Vanderplank, “Deja vu? A decade of research on language laboratories, television and video in language learning”, Language Teaching, 43(1), January 2010, 1–37.

Koolstra, C., Jonannes, W., and Beentjes, J., "Children’s vocabulary acquisition in a foreign language through watching subtitled television programs at home", Educational Technology Research & Development, 47(1), March 1999, 51–60.

Uchikoshi, Y.. "English vocabulary development in bilingual kindergarteners: An individual growth modeling approach", Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 9(1), February 2006, 33–49.